When you picture different athletes—cyclists, gymnasts, and Olympic weightlifters, for example—you likely categorize them instinctively by their height, size, and build. But the differences in athletic expertise extends beyond those that meet the eye.

Physiological differences in muscle fiber distribution—fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscle fibers, to be exact—play a role in exercise performance, and may make one person more inclined to perform well in one sport, compared to another.

While your genetics play a role in muscle fiber distribution, how you train and adapt muscle fibers is an interesting part of exercise science. So, regardless of your inherent genetics, here’s what you need to know about training fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscle fibers, based on your favorite sport.

More From Bicycling

What are fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscle fibers?

In the most broad of strokes, fast-twitch fibers refer to those responsible for faster, more powerful movements (think sprints and plyometrics). And conversely, slow-twitch fibers refer to those responsible for slower, sustained movements and exercises (think long rides and walks). Everyone has both types of fibers and both are critical, not just for exercise, but for daily life and the different movements we all perform throughout the day.

This high-level reminder is important, because often when discussing muscle fiber types, the discussion revolves around sports. And if you’re a sprinter, having more fast-twitch fibers is “good” and having more slow-twitch fibers is “bad,” with the reverse being true if you’re a long-distance rider. But considering most people spend their days walking around the office, playing soccer with their kids, or sitting at a desk, the concept of “good or bad” muscle fibers is moot, considering both play an important role in everyday life.

To distinguish between fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibers, though, you can look at their internal makeup. “Slow-twitch and fast-twitch muscle fibers are differentiated by properties related to their molecular composition and metabolism, which causes them to have differences in contraction time, fatigability, and duration of use,” explains Joshua Scott, M.D., primary care sports medicine physician at Cedars-Sinai Kerlan-Jobe Institute in Los Angeles.

Here’s how they differ, in more detail:

All about slow-twitch muscle fibers

“Slow-twitch muscle fibers contain high levels of mitochondria and myoglobin, an oxygen-binding protein that can release oxygen for energy production during exercise,” Scott explains. Because slow-twitch muscle fibers store high levels of oxygen, they are able to participate in slow force generation contractions for long periods of time without fatigue. These properties make them useful to endurance athletes, such as cyclists, who compete for extended periods of time, he says.

Think for a second about the difference between cardio exercise (cycling longer distances, running, swimming, or cross-country skiing) and performing exercises that require power or speed (sprinting, heavy strength training, high-jumping, or throwing the javelin). Maintaining activity during a cardio workout requires your oxygen intake to keep up with your muscle’s energy requirements. You get into a rhythm where, even if you’re breathing at a heavier rate, you’re breathing in a controlled way that you’re able to maintain. It’s this steady flow of oxygen that’s providing the fuel source for your slow-twitch fibers—those mitochondria-filled, oxygen-loving fibers—in your working muscles.

All about fast-twitch muscle fibers

If you go from a slow ride to an all-out sprint, very quickly you realize your oxygen intake can’t keep up with your muscles’ oxygen requirements. Even as you breathe faster and deeper, your muscles start to burn and you start to tire. When oxygen isn’t sufficiently available to fuel your slow-twitch muscle fibers, your fast-twitch fibers take over.

“Fast-twitch muscle fibers contain low levels of mitochondria and myoglobin, making them rely on anaerobic metabolism for energy production. Instead of oxygen, these fibers utilize creatine phosphate to create quick and powerful muscle contractions that are shorter in duration and more sensitive to fatigue. These properties make fast-twitch muscle fibers useful to powerlifters, sprinters, and other athletes who require short bursts of energy,” Scott says.

All of your muscle groups have both fast- and slow-twitch fibers, but distribution varies

The very fact that you can move from a sustained, oxygen-fueled ride to an all-out sprint is evidence that your muscles contain both types of muscle fibers. You’re using the same general muscle groups whether riding slowly or riding really fast, but the activity you’re performing determines which fibers play a predominant role in energy production.

“The proportion of slow-twitch to fast-twitch muscle fibers in a particular muscle varies depending on the function of the muscle and the type of training in which an individual participates. For example, muscles involved in maintaining posture tend to have more slow-twitch fibers while muscles involved in weightlifting will have more fast-twitch fibers,” Scott explains.

What determines your distribution of fast-twitch versus slow-twitch muscle fibers?

Genetics

Just as genetically-determined height can play a role in which sports or activities you may be more inclined to excel at (shorter individuals in gymnastics; taller individuals in basketball), genetically-determined muscle fiber distribution can, too. If you have more slow-twitch fibers, for example, you might excel more at a long-distance ride than a sprint. That said, unlike height, there’s evidence that specific types of training can change muscle fiber distribution.

“Genetics generally have the most control over your fiber distribution,” says Hannah Dove, P.T., D.P.T., C.S.C.S. at Providence Saint John’s Health Center’s Performance Therapy in Santa Monica, California. A fact that’s particularly true of those who are “blank slates” when it comes to sport-specific training. In other words, what you were born with may automatically predispose you to be better at one type of activity or another. If you want to ride centuries and your body already has more slow-twitch fibers, you might be predisposed to be good at riding those longer distances. But, if your muscles are composed of more fast-twitch fibers, you would have the capacity to be a better sprinter, Dove explains.

This genetic predisposition may play a fairly significant role in high-level competition in sports. “Genetic predisposition is set in the developmental years and sets the overall composition of the muscle,” says Lem Taylor, Ph.D., director of graduate studies in the Mayborn College of Health Sciences at the University of Mary Hardin-Baylor in Belton, Texas. “Elite endurance athletes may be born with a 72% to 28% slow- versus fast-twitch composition, whereas most people are in the middle of the normal distribution—roughly 50/50 of each.”

The natural question, then, is what type of muscle-fiber distribution are you working with? Well, it’s a little tricky to know for sure. For one thing, muscle fiber distribution varies between muscles themselves, so the exact distribution you have in your calves may be different than what you have in your deep core muscles.

Second, to get an accounting of your muscle fiber distribution, a muscle biopsy is the only truly accurate way to know. This is an invasive procedure that needs to be performed in a lab or medical setting… and if you don’t like needles, it may not be a test you want to get done.

There are other, non-invasive ways to get an idea of what your muscle fiber distribution might be based on multiple rep testing from a one-rep max (that’s how much weight you can lift for just one rep), but the accuracy could be limited. “I’m not a big believer in those fitness tests,” says Taylor. “It’s all based on rep ranges, and we know repetitions to failure may be influenced by [muscle fiber type], but it’s also highly influenced by training and overall current level of muscular endurance. They don’t have much application to administer from a standpoint that would predict success in a particular athletic event.”

If you’ve ever taken a genetic test to gauge your fitness abilities, you might have gotten an assessment of your muscle fiber breakdown. Taylor explains that these tests do have some validity, but results should also be taken with a grain of salt. “The most common test would be for the ACTN3 gene and its three genotypes. Expression of a particular genotype is more connected to the fast-twitch characteristics,” he says.

So if you happen to test high for that phenotype, there’s a reasonable probability that you have a higher number of fast-twitch muscle fibers, but there’s no good test for slow-twitch fiber distribution. “One could possibly work backwards… if they didn’t express the [fast-twitch] genotype, they could assume more slow-twitch [fibers]. But again, there are caveats to that gene, and research to support that athletes in high-level competition for anaerobic sports don’t always express the most fast-twitch version of that gene.”

Short of a muscle biopsy, the science just isn’t there yet for a non-invasive and reliable muscle fiber distribution test.

The type of training you do

Genetics doesn’t tell the full story, though, especially in those who have been training or participating in sports for years. In these individuals, their training’s influence plays a role in their success in their chosen sport. “There is some genetic component that may cause some individuals to have more of one type of muscle fiber compared to others, but there is evidence that muscles are able to adapt and switch muscle fiber types with specific training,” says Scott. An individual who is training for longer distances will have more slow-twitch muscle fibers in their leg muscles compared to an individual training for short-distance sprinting, who will have more fast-twitch muscle fibers.

In these examples, it’s a little tricky to know which came first—the training or the muscle fiber distribution? In other words, did those genetically graced with more slow-twitch fibers naturally choose to train for endurance activities and events, and those graced with more fast-twitch fibers gravitate toward more fast, powerful events? Or did they follow their passion and experience muscle fiber changes based on their training to support their activities?

So far, the jury is still out. The science is still relatively new, and there exists a high between-person variability when it comes to training response. So where one person might respond significantly to training, another might not.

“We know the easier transition in fiber types can come with endurance training,” says Taylor. “It’s probably around a 35% to 55% range for the role that genetics plays in how much this can change, as we know there is a lot of variability [between individuals]. A ‘low responder’ to exercise training in general isn’t going to have much control over [the change in muscle fiber distribution], while a ‘high responder’ to exercise training will have the opposite effect.”

So if you’re someone who trains and trains and trains but struggles to see improvements (whether in endurance or strength), you likely fall in the low responder group, and would struggle to experience changes in your muscle fiber distribution.

The takeaway here is that you shouldn’t let your possible genetic distribution affect your choice of sports. “In each sport it is important to train for the demands of that sport, which a performance coach or strength coach can help you achieve if you don’t know where to start or how to train correctly,” says Dove. And this training plays a considerable role in how your muscle fibers change and develop, and how you’ll perform within the sport.

How can you train fast-twitch versus slow-twitch muscle fibers?

When it comes to training your muscle fiber types, especially if your goal is to accrue more of one type than another for a particular sport, you need to think about the specific needs of the sport itself.

The best activities for slow-twitch muscle fibers

“In order to enhance slow-twitch fiber performance, you would want to focus on endurance training,” says Dove. This may mean long rides, swims, runs, or strength exercises that challenge your muscular endurance. Keep in mind that “long” is relative. Regardless of muscle fiber distribution, you’re also working with your current level of cardiovascular and muscular endurance.

If you haven’t been training for any type of endurance event, starting a beginner training plan has the ability to improve your overall endurance, and with time and continued training, may also help alter your muscle fiber distribution based on your personal ability to do so.

It also may mean adding endurance-specific strength training to your routine. “Doing higher reps at a low weight or resistance [builds muscular endurance],” explains Dove. “The general rep schemes for endurance are 12 to 20 reps for 3 sets with a light weight.”

The best activities for fast-twitch muscle fibers

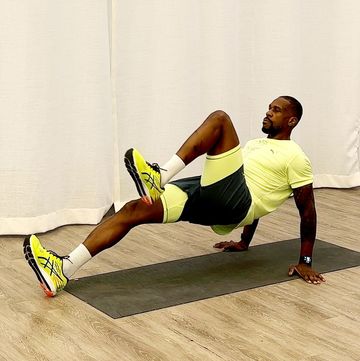

If you’re training for an event that requires power and speed, whether it’s a riding for a mile or a weightlifting competition, you’ll want to balance training for that sport with other strength training and power activities that further challenge your fast-twitch muscle fibers. “This generally means lower reps, but higher weight,” Dove says. “You could also work on explosive training such as plyometrics, jumping, and sprinting.”

To focus on fast-twitch fibers in your strength sessions, focus on a rep scheme of 6 to 8 reps for 3 to 4 sets at a heavier weight, closer to your one-rep maximum. “Sprinting, jumping, and plyometric exercises are also performed fewer times due to the high-intensity, short-duration nature of the moves,” Dove says.

The bottom line on fast-twitch versus slow-twitch muscle fibers

At the end of the day, you’re likely not going to get tested with a muscle biopsy to know whether you have a greater personal distribution of fast-twitch versus slow-twitch muscle fibers in a particular muscle group. Even if you were tempted to get tested, distribution varies between muscle groups, so knowing the distribution in your quadriceps, calves, or glutes certainly is interesting information to have, and likely gives you a snapshot of overall distribution, but may not tell the full story.

The main thing to remember is that everyone has both types of fibers, and most sports and activities actually do require use of both. Think about sports like soccer, tennis, or basketball—each requires endurance, speed, and power to varying degrees, which means all of your muscle fibers are needed to play their given roles.

Regardless, training does make a difference in how your muscle fibers develop, so if you want to try an activity, it shouldn’t matter what you’re genetically inclined to do. Enjoyment in sport is every bit as important as performance. And if you enjoy your sport, and you train accordingly, your performance will improve as your muscle fibers adapt to support your sport and training.

Laura Williams, M.S., ACSM EP-C holds a master's degree in exercise and sport science and is a certified exercise physiologist through the American College of Sports Medicine. She also holds sports nutritionist, youth fitness, sports conditioning, and behavioral change specialist certifications through the American Council on Exercise. She has been writing on health, fitness, and wellness for 12 years, with bylines appearing online and in print for Men's Health, Healthline, Verywell Fit, The Healthy, Giddy, Thrillist, Men's Journal, Reader's Digest, and Runner's World. After losing her first husband to cancer in 2018, she moved to Costa Rica to use surfing, beach running, and horseback riding as part of her healing process. There, she met her current husband, had her son, and now splits time between Texas and Costa Rica.