If you’ve retained one piece of information related to mitochondria, it’s probably the term “powerhouse of the cell.” While that’s accurate and easy to remember, it’s not all that informative or applicable to your cycling workouts.

Ready to dust off your microscope and go a little deeper? A better understanding of how mitochondria work will give you a leg up when building your training program and planning your rides.

What exactly are mitochondria?

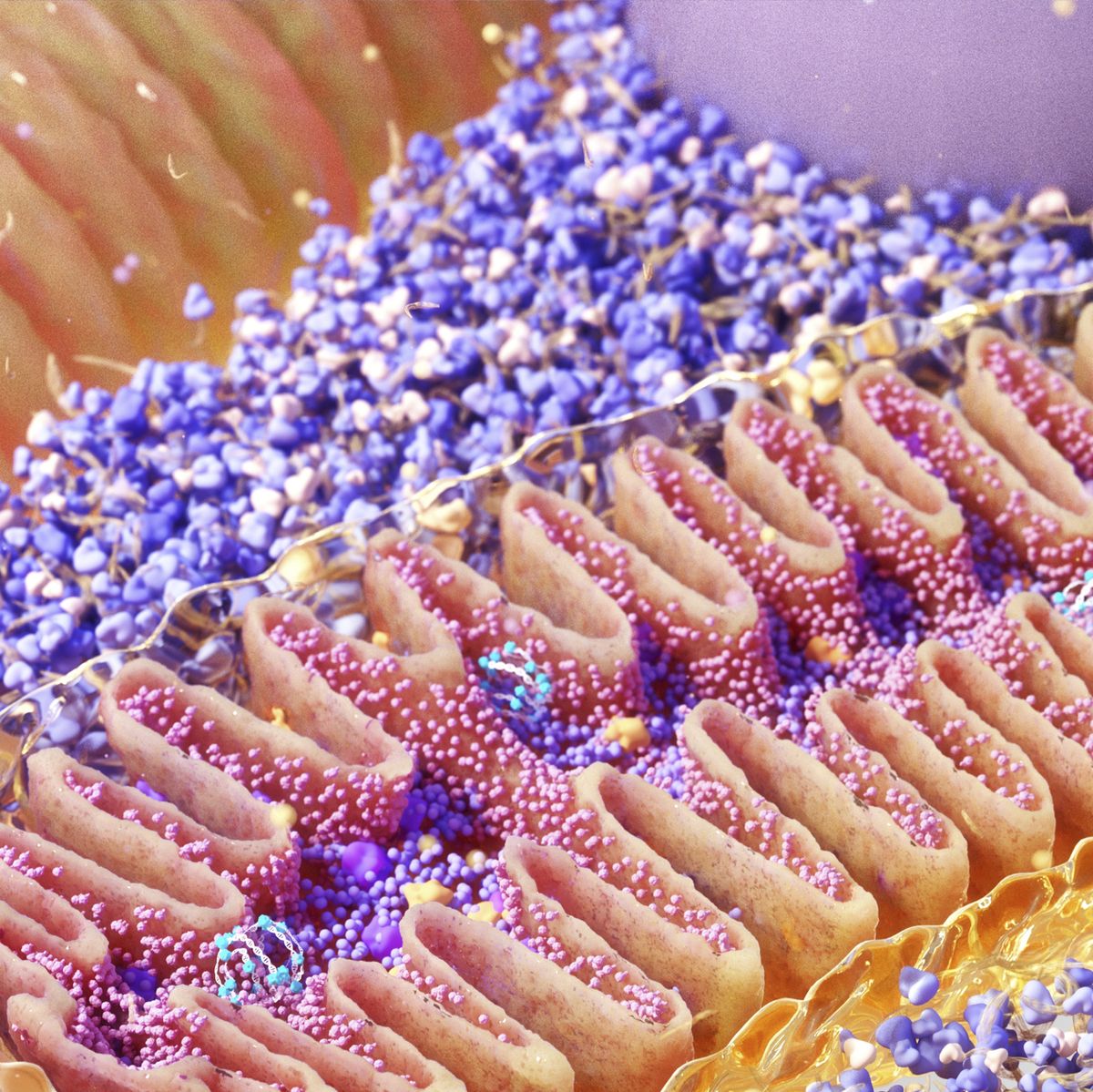

Mitochondria are microscopic, membrane-bound structures known as organelles. They’re found in most of the body’s cells, with the exception of red blood cells. Cells that require a lot of energy (that is, those in your muscles), contain hundreds or thousands of mitochondria, explains Todd Buckingham, Ph.D., chief exercise physiologist at The Bucking Fit Life, a wellness coaching company and community.

More From Bicycling

Like all organelles, mitochondria is tasked with a specific function. And for mitochondria, that role is energy production, hence their “powerhouse” moniker.

Mitochondria serve as an intracellular factory for adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the continuously generated molecule often referred to as the body’s “energy currency.” Through a series of complex chemical processes, mitochondria use the oxygen we breathe in through our lungs and the nutrients we consume to produce ATP, which the body then “spends” to execute everything from essential biological functions to hour-long sweat sessions.

What role do mitochondria play in ride performance?

“Mitochondria play a vital role in endurance cycling performance,” says Buckingham. “Cycling is an endurance sport that relies heavily on aerobic energy production—that means using oxygen to provide the body with energy—and the mitochondria are what turn the oxygen into energy, or ATP,” he says.

The more mitochondria you have in your cells (your muscle cells, specifically), the more muscle-contracting energy you can produce. That translates to more efficient pedaling and endurance workouts that feel less grueling.

How do you increase mitochondria?

The number, size, and quality of your mitochondria are largely determined by your genetics. While there’s some research that suggests that, in rare cases, mitochondrial DNA can be inherited from both parents, it’s almost always exclusively passed down from the maternal side. (“If you’re a great endurance athlete, be sure to thank your mom,” Buckingham says.)

Regardless of your genetic lottery winnings (or losses), you can improve upon your mitochondrial baseline through exercise. Research shows that working out is the best way to increase the number of mitochondria in the cells and it improves their quality.

A recent review article published in Frontiers in Physiology describes part of the physiological process that happens when you exercise: “In response to exercise, mitochondria increase ATP synthesis rates to address the cell’s metabolic requests. To this aim, several nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins are activated to induce MQC [mitochondrial quality control] and recover mitochondrial function,” the research reads.

Translation: Your cells want (and need) energy during exercise, and mitochondria works to produce more of the energy provider (ATP). In return, the body increases mitochondrial quality and function so it can keep producing that energy.

What that means for your workouts? If you want ride longer or at higher intensities, then you have to practice exercising longer and harder. That is what will enhance your mitochondrial function and eventually, make your efforts feel easier.

What type of exercise is best for increasing mitochondria?

Aerobic training, or exercise that utilizes oxygen and lasts for at least five continuous minutes, will positively impact mitochondria. However, the type of effect it has on mitochondria will depend on the intensity of exercise, says Buckingham.

“Low-intensity training will increase the number of mitochondria that we have in the cells. High-intensity training increases the size of the mitochondria,” he says.

Buckingham continues: “I like to use this example: Think about a single mitochondrion as a school bus. The oxygen molecules that we breathe in are kids looking to get a seat on the school bus. If we have more school buses, we can get more kids on the buses. At the same time, if we have bigger school buses, we can get more kids on those school buses as well. So, by increasing the size and number of mitochondria in our muscles, we can get more oxygen into the mitochondria, and therefore, we can produce more ATP and provide the body with more energy.”

This is why you want to incorporate both low- and high-intensity rides into your training plan to receive the full range of benefits.

Training anaerobically, or without oxygen (think 60-second, all-out sprints) won’t impact your mitochondria, as they aren’t involved in providing the body with energy during this type of training. But there’s still value in exercising at ultra-high intensities for very short periods of time, Buckingham says. “[Anaerobic training] will improve the function of lactate transporters in the muscle, which is another important part of the training process to improve aerobic endurance performance,” he says.

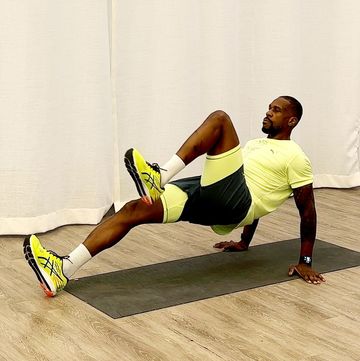

Does resistance training influence mitochondria?

What you do off the bike and in the weight room may also impact your mitochondria. In one study published by Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 11 healthy but untrained men participated in a 12-week resistance training program.

The subjects performed a full-body strength workout three times a week. The study concluded that “12 weeks of resistance exercise training resulted in qualitative and quantitative changes in skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiration” and that “resistance exercise training appears to be a means to augment the respiratory capacity and intrinsic function of skeletal muscle mitochondria.”

So just like aerobic training, resistance training can improve the quality and function of these cellular power providers—which means, if you needed another reason to make time for strength training, look no further than your mitochondria.