Poop has always been a slightly taboo but important topic for endurance athletes. Heck, it cost Tom Domoulin a stage win a few years back. Most of us have had at least one sprint-for-the-toilet situation, exacerbated by bib shorts that didn’t have an emergency release flap.

Your poop isn’t just something to deal with preride by drinking a lot of coffee to get things moving, either. It’s an important measure of overall gut health, and it may tell you that you need to make some dietary or lifestyle changes to optimize your health and your training.

Why does our poop matter?

How our poop looks is usually a good early indicator that things are going awry, or that all systems are “go.” For athletes, this is even more important, because we’re potentially more vulnerable to gut issues, and a grumpy gut can mean the difference between a top 10 finish or an Uber home from the porta potty.

More From Bicycling

“Keeping tabs on our poop provides a view—albeit limited—into a body system that is otherwise hidden from us,” explains Patrick Wilson, Ph.D., R.D., an associate professor of exercise science at Old Dominion University and author of The Athlete’s Gut. “A corollary would be the way we can use resting heart rate to get an idea about what might be happening with our cardiovascular system.”

“We’re learning more about the gut microbiome and the GI system as a whole and we’re beginning to understand the role it plays in our overall health,” says dietitian and FlyNutrition owner Kylee Van Horn, R.D. “And poop is one of the most visible indicators of gut health. We know that the gut relates to immune system health and mental health.”

Why do athletes specifically need to care about poop?

Why are runners and cyclists perpetually comparing bowel movements or making jokes about needing to pull off into the ditch? It’s not that sport is bad for the gut, exactly. But intense physical effort does influence the motility of the stuff in our GI tracts, and it can exacerbate small issues that may not have plagued you if you weren’t going for a new power threshold. In short, training stirs the pot—the pot being our guts.

“Exercise, particularly the intense or prolonged kind, challenges the gut’s ability to carry out its basic functions like nutrient absorption and protecting us from harmful pathogens,” says Wilson. “Ultimately, skeletal muscle and skin get a large piece of the resource pie during exercise, leaving the gut under-supplied with blood and oxygen as compared to at rest.”

Not only are we moving more and quite literally stirring shit up (sorry), we’re also eating more simple carbs in the form of sports drink, gels, and bars, and we’re more likely to eat more than our sedentary counterparts, which requires more work for our gut to process it all. We tend to go up and down in our hydration status more than your average Joe, too.

You may have also heard that during exercise, blood is shunted away from the gut and diverted to the legs so you can pedal with power—that’s great for your power numbers, but less than ideal for your gut health.

Athletes can also suffer from malabsorption of certain micro and macronutrients if their guts aren’t in great shape. To put it bluntly, you’re pooping out the good stuff along with the extra material. Van Horn says she sees athletes who struggle with low ferritin levels despite supplementation—the low levels persist because the gut isn’t actually absorbing the nutrients.

“I’ve found that a lot of athletes do tend to have hyper-permeable intestinal walls, which you may have heard called ‘leaky gut,’” says Van Horn. “This can happen due to the stresses that we’re under when we’re exercising a lot. The cells that make up your gut lining become more permeable, and that can cause serious issues—or just a lot of discomfort on and off the bike.”

Van Horn also sees a lot of athletes who have seemingly chronic diarrhea, especially while in the middle of exercising. “Obviously, having to stop all the time during your training is really annoying—but it can also be an indicator that something is going wrong in your digestive system,” she says. “It’s ruining your training, but we also need to figure out what it is doing to your overall health.”

Now, before you hang up your cycling shoes forever, there’s a caveat: It’s unlikely that your gut issues would disappear if you stop exercising. “Part of why athletes seem to have more of these issues could just be because athletes tend to be more in tune with their bodies, and are noticing these problems,” Van Horn says. “The average person may just be ignoring some of these symptoms.”

Also, some of these problems are acute—based on what you ate in the last couple of days, illness, or even stress—and you can generally manage these issues with small changes. For example, ensuring that you’ve given yourself time to have that morning bowel movement before hopping on the bike, getting enough fiber in your diet, avoiding foods that you know trigger bouts of constipation, and staying adequately hydrated can all help avoid the occasional stomach upset.

However, if you’re experiencing constipation or diarrhea (or a mix of both) on a regular, ongoing basis, that’s a sign you need to get some help to start the troubleshooting process.

Not sure if your poop is optimized? To understand if you have an issue to worry about, it’s important to get a handle on what “good poop” and conversely, “bad poop” looks like.

What exactly is a ‘good poop,’ anyway?

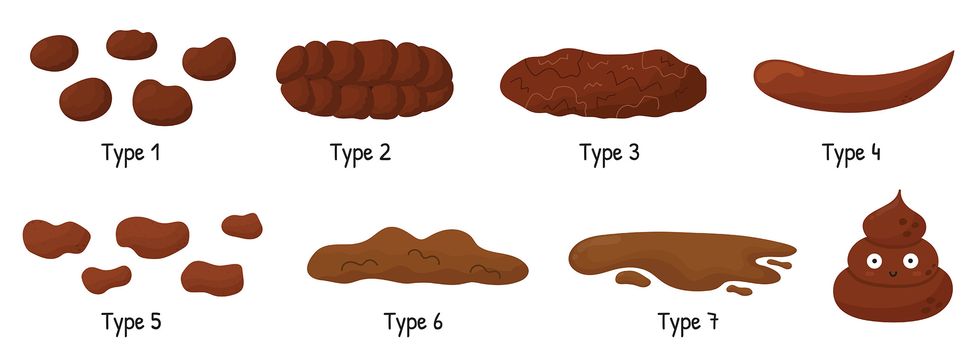

Here, we defer to the Bristol Stool Chart, which covers the range of shapes and consistency of your bowel movements. In general, Van Horn says the goal should be Type 4 poop—smooth and sausage-like—but if yours veers into cracked or a little less defined, that’s likely fine.

Type 1: Separate small hard lumps (may be constipated)

Type 2: Sausage shaped, but lumpy

Type 3: Sausage shaped with cracks on the surface

Type 4: Sausage shaped and smooth (this is optimal!)

Type 5: Soft blobs, but with defined edges (bordering on diarrhea)

Type 6: Fluffy pieces with ragged edges

Type 7: Entirely liquid (diarrhea)

What does your poop say about you?

Your poop can be a cry for help. Larger shifts in consistency, like diarrhea that lasts for days or the sudden need to go often during a ride can indicate that something has changed in your gut that needs to be addressed.

“Look at the number of bowel movements that you have every day, and what those bowel movements look like,” says Van Horn. “If it’s not formed stool or if it’s really hard stool, then that’s an indicator that something isn’t right. Are you hydrating enough? Are you eating enough fiber? Is something off with your microbiome? Use your poop as a signal to check in.”

A change in your digestive situation could even indicate that you’re edging into relative energy deficiency in sport (REDS) territory. “Your GI symptoms and stool consistency might also be impacted by energy availability,” says Wilson. In fact, GI distress is one of the symptoms of REDS, though experts still aren’t exactly sure of the connection.

Don’t panic if you have one weird day with your bowels. “Don’t expect it to be the exact same every time you go,” Van Horn says. “Because there are so many things that can affect it, it’s unlikely that you always have the exact same type of poop.”

However, if you’re not between Type 3 and 5 most of the time, that could indicate a problem—it might be time to check with an expert.

What is a normal poop schedule like for a healthy athlete?

“Everyone has a different transit time,” says Van Horn. Still, there are some basic guardrails: You should be pooping once a day, but not more than three times per day. And according to the American Journal of Gastroenterology, normal frequency can mean going just three times a week. If you’re going less often than that, though, consider it a red flag.

Not to make it weird, but one final caveat: For those who are pretty constipated, pooping out one or two small pellets doesn’t count as a full bowel movement.

However, don’t expect to poop at the exact same time (or same consistency) every day if you’re changing up your training or your diet. If you ate a lot of high-fiber foods for dinner the night before, you may have a speedier, heftier bowel movement in the morning compared to the smaller poop that you may have if you had a smaller, less fiber-rich meal.

If you’re someone who stresses about their bowel movements on race day, Van Horn suggests keeping a poop and food journal to start to see how timing of certain meals impacts your bathroom breaks. There are other factors that play into your bowel movements, too, like stress, hydration, and movement, but you’ll still get some good insights.

Do you need to poop preride?

You probably have heard the jokes about doing shots of espresso preride not just for the wake up, but because caffeine stimulates your system and speeds up the process of shedding those last ounces of “extra weight” in the form of number two.

While yes, that espresso might work, if you’re not a caffeine lover, you can skip it. “There is some evidence that caffeine stimulates colon activity and the urge to have a bowel movement,” say Wilson. “That said, simply eating or drinking also does that, so for many athletes it is not necessary to seek out caffeine for the specific purpose of triggering a bowl movement. When I compete in races, I make sure to wake up early enough so that I can eat and have a bowel movement before I head out the door.”

Also, while bowel movements might happen before a morning ride for some people, for others, it might happen when they get home. Don’t stress if you’re not a morning pooper.

What do all the gels, bars, and sports drinks do to our digestion?

Seriously, how many gels is too many gels before things start to clog up? Well, when your system gets hit with too many carbs to handle, that’s when things can go wrong. And it’s a delicate balance when it comes to getting enough fuel to keep pedaling hard, but not so much that you need to pull over to find a toilet.

“It largely comes down to the rate of carbohydrate feeding,” says Wilson. “The higher the rate of feeding, the higher the probability of having some gut issues.” He notes that some studies suggest that more solid foods, like bars, may cause more gut issues, especially if you’re sensitive.

Generally speaking, cyclists should be taking in between 200 and 400 calories per hour in the form of simple carbohydrates. You may find that gels or sports drink mix go down smooth, or maybe you prefer bars, homemade rice cakes, or even baked goods like cookies. It’s important to experiment to see what makes you perform your best while also feeling good on the bike—and never try something new on race day!

Hydration also plays into gut distress and its potential to cause untimely number-two urges. Aim to drink roughly one regular sized water bottle per hour (a bit more if it’s hot out or you’re a heavy sweater) to give your gut the fluid it needs to process the carbs. Otherwise, you may experience some serious discomfort on the bike, as well as postride.

Lastly, timing and frequency matter: Try to avoid chugging a whole water bottle in one shot or downing four gels all at once. Often, this can lead to serious GI distress. Think small amounts of carbs and water on a frequent basis—you can even set a reminder on your phone to ping every 15 minutes if you know you struggle with fueling consistency.

Athletes and fiber—what’s the balance for optimal pooping?

We know that as athletes, there are times when we need to drop our insoluble fiber intake down in order to prioritize simple carbohydrates, like rice and pasta. But we also know that fiber is critically important for good gut health and motility, so what’s the balance between performance and overall health?

Sorry, you don’t get a pass to skip broccoli at dinner tonight, unless you’re racing very soon.

“For the most part, the only time it makes sense to me to drop fiber intake substantially is over the few days before races,” says Wilson. “It might reduce the likelihood of having certain GI symptoms during racing.”

If you eat a diet that is high in fiber—lots of vegetables, beans, and fruit—start scaling back a few days ahead of your race, and as it gets closer, cut back further. This just means skipping or scaling down intake of fiber-rich foods like broccoli, kale, or black beans. Or have a rice bowl rather than a salad.

It may take doing this during a few race weeks to figure out what feels best for you, because everyone reacts to fiber differently. Your goal is that on race morning, you’re able to have a solid (Type 4) poop before your race, and head to the start line not feeling as though you need to race the peloton to the first porta potty on the course.

What can I do at home to improve the quality of my poop (and my gut health)?

Start with a food log and write down everything you eat and drink for a few days and add notes about when you’re pooping and the consistency.

Then, do a scan of the food log: Does it seem like you’re well-hydrated? Are you eating a lot of fiber-rich foods? Are you eating a wide variety of plant-based foods?

“I like starting with food-related interventions,” says Van Horn.

After looking at your food log, ask yourself:

What prebiotic-rich foods can you add in? Once a day, could you add one serving of resistant starch, like rice or potatoes that have been cooked and then cooled? (To make a starch into a resistant starch, which is the optimal prebiotic snack, you need to first heat and then cool it.)

Can you add a serving of fermented foods to your plate, like sauerkraut, kimchi, yogurt, kombucha or a serving of unpasteurized pickles? And you don’t need to overdo this: Just a tablespoon or two is plenty.

Can you add a wide variety of foods that grow from the ground into your diet? If we can get a little bit more variety in our diet, sometimes that can actually encourage a healthier and more diverse microbiome. This could mean eating whole wheat pasta, brown rice, or quinoa, rather than sticking with white rice. Aim for around 30 different foods from the ground per week as a starting point.

When should I get help?

First and foremost: “You always want to check with a doctor if you notice blood in your stool,” says Van Horn. But if your poop is simply a little looser or more compact that is considered ideal, you may want to start with a dietitian who works with athletes.

Dietitians are more likely to look at an athlete as a whole, rather than—pardon the pun—a series of holes. A GI doctor may recommend a restrictive food protocol without much context, or order invasive testing like a colonoscopy or endoscopy before trying less painful protocols.

“I’ve found that PCR stool testing has been very helpful for many of my athletes,” says Van Horn. “It’s a stool test that provides a great analysis that can point us in certain directions.” (For example, the poop test can pick up on things like yeast or bacterial overgrowths that lead to GI issues, which can then be treated.)

TL;DR: If your poop is impacting the way that you race or train, or causing you physical (or emotional!) discomfort, it’s time to make some changes and an expert can help.

Molly writes about cycling, nutrition and training, with an emphasis on women in sport. Her new middle-grade series, Shred Girls, debuts with Rodale Kids/Random House in 2019 with "Lindsay's Joyride." Her other books include "Mud, Snow and Cyclocross," "Saddle, Sore" and "Fuel Your Ride." Her work has been published in magazines like Bicycling, Outside and Nylon. She co-hosts The Consummate Athlete Podcast.