On the first day of 2022, I did a foolish thing. Buoyed by all the shiny possibilities of a new year, I signed up for the Off-Road Assault on Mount Mitchell (ORAMM), a 60-mile mountain bike race with 10,500 feet of ugly uphill on and around North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Parkway—in the hottest part of summer: late July.

It was the last thing I needed in my life. It was the exact thing I needed in my life. I am the poster child for hustle culture run amok. I’ve monetized all my hobbies into three very demanding jobs. I’m a full-time research producer on a true-crime TV series. I write for newspapers and magazines. In my “free hours,” I manage a 45-acre regenerative farm. That mostly means sprinting from one emergency (the sheep have worms!) to the next (the dog thinks the baby chicks are popcorn shrimp!).

After 10 years as a gig-economy worker, I realized everything in my life was in service of another dollar. Here held the allure of a long-distance mountain bike race: I’ll never monetize mountain biking. I wince at anything off-camber and creep through rock gardens. Prepping for ORAMM would be simply in service to me.

An eternal optimist about my time-management abilities, I sent off my registration and spent about three months training sporadically. Then I panicked. Twelve weeks before ORAMM, I enlisted the help of Christopher Harnish, PhD, an exercise physiologist, coach, and chair of the Department of Exercise Science at Mary Baldwin University in Staunton, Virginia. As he’s a former USA Triathlon Off-Road national champion, dad, and full-time academic, I knew he’d understand how to make the most out of minimal time.

It’s entirely possible to take on any of the marquee gravel races, or a mountain bike marathon, or a gran fondo, without your training feeling like a second (or third, or fourth) job, says Harnish. It might even be the best way to train.

“Regular people train too damn much,” he says. “They’re always tired and it’s because they’ve got a real life, kids, and work.” Training less with more time to recover is going to get you just as fit, he adds, as someone who is skimping on sleep to jam more hours and workouts into their week.

If you can train an hour a day—and slightly more on the weekends—you can tackle just about any big ride, Harnish says. For ORAMM, a race I hoped to finish in 10 hours, my weekly training typically totaled 7 to 9 hours, with a peak of 12.5 hours. Here’s the advice that made it happen.

Give Yourself Time to Build Up, and Screw Up

➤ Eight weeks is generally the minimum to prepare for a big event, but it’s far better to start at least 12 weeks out, says Harnish. “It’s enough time for you to build; it’s enough time for you to make, and recover from, mistakes,” like doing a few too many hard workouts in a row and needing extra rest, or bonking on a crucial long ride and having to Uber home. Give yourself 16 weeks if you’re starting with minimal fitness.

Ideally, you’d map your schedule out in monthlong blocks. Three weeks would be spent building fitness followed by a recovery week. Harnish says three weeks is enough time to focus on an objective—like improving aerobic capacity—without risking overtraining. It’s crucial to plan out blocks beforehand; otherwise it’s tempting to push for three, then four, then five weeks before realizing you need a break. If your life is chaos, like mine, you may not be able to stick to the perfect 3:1 ratio. Don’t sweat it. Find the weeks that are already a tangle of social commitments and responsible adulting and designate them as your recovery weeks. For me, times with heavy farm commitments—stacking hay or castrating bull calves—became down weeks. This let me not stress about fitting it all in during times that “all” was just too much.

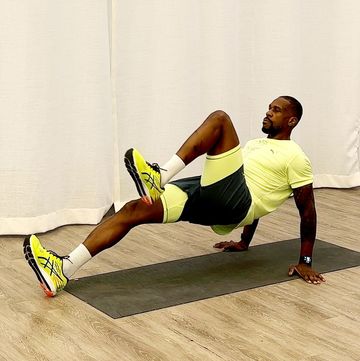

Your Most Efficient Workout Is Going Really Fast

➤ Tuesdays were for short, high-intensity intervals, usually on the trainer. Research shows that high-intensity efforts spur metabolic changes—specifically by building mitochondria, the powerhouses of your cells. Having more mitochondria boosts performance in events of any distance.

However, intervals are hard on your body. “There’s a limit to how much high-intensity work will help you,” says Trevor Connor, a former pro cyclist and founder of Fast Talk Labs, adding that research shows that two weekly sessions are all you need. You won’t necessarily benefit from a third session, he says, and four can be too much to recover from. Though painful, these sessions are blissfully brief. Sometimes it’d simply be 10 30-second sprints. But for my favorite, called “Fibertap,” I’d complete a set of 4 x 2:30 efforts plus a few 30-second sprints as a stinger at the end, then wobble my way toward the shower. (Check out 3 Key Workouts below.)

Get Intensity and Volume in One Ride With Tempo

➤ After a rest-ish day of an easy hour spin or 40-minute jog, I would kit up on Thursday for a tempo or “sweet spot” training session. Typically, these workouts would have me doing 15-minute intervals at about a 7 on a 1-to-10 scale of suffering, where 10 is agony. I’d repeat these 15-minute efforts two or three times with four or so minutes of recovery between efforts. At exactly the one-hour mark, I was ready for a nap and a snack.

In recent years, short, painful intervals like my Tuesday sessions have been the darlings of the endurance world. Some coaches, like Connor, even go so far as to say training in the middle of your athletic capacity—at tempo—isn’t worth the time investment. Connor feels that even though these workouts are hard, they don’t spur as much improvement to your mitochondria as high-intensity rides do. However, some experts, like Andrew Richard Coggan, PhD, the director of the Exercise Physiology Laboratory at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, feel that time spent in the middle range of your athletic capabilities allows you to integrate both intensity and volume into a single workout. And Harnish believes tempo can be a useful tool. “There’s nothing magical about any intensity,” he says. “Some are best for certain outcomes, but all are helpful.”

For me, these workouts were also confidence boosters. On race day, I tempo’d my way up long climbs. My training was a crash course in what to expect when you’re expecting to suffer.

Shorten Your Long Ride with a Little Effort

➤ If intensity is starting to look like a magic bullet for decreasing your training time, know that intervals alone will not get you to the finish line. Long rides still matter.

After three or so hours of steady cycling, your body ramps up production of both growth hormone and cortisol, which help you utilize stored fat as fuel, says Harnish. Getting your body to run efficiently off of fat is a worthwhile endeavor for anyone racing for hours and hours. Mentally, you also need to know the impending hell you’ve signed up for. I told Harnish early on that I didn’t have time for huge rides. I do 90 percent of my farmwork on weekends. Heading out for six hours every Sunday wasn’t going to fly. Harnish had a workaround.

First I pre-fatigued my legs on Saturday with a shorter effort—like a 90-minute ride with a few tempo efforts mixed in. And on Sunday I’d ride for three to four hours and add intensity at either the very beginning or the very end to reduce the amount of time I needed to grind away. Some weeks, I’d start with a set of 4 x 4 minutes of hard effort up a climb, then head off for three more hours of riding. Other weeks I’d put in three hours and finish with an interval set, or come home and put in a 20-minute time trial on the trainer.

Brutal? Yes. But they were absolutely effective.

In a long race like ORAMM, muscle cramps are the nemesis of most amateur racers. Harnish was frank with me: At some point in the day, I would cramp. His job was to make sure I didn’t cramp until the very end. While scientists still don’t fully understand the mechanisms that cause muscle cramps, research shows they’re likely the result of overexertion, says Harnish. If we could get me to cramp during a long ride, we’d know my limit and then work to extend it. But that can take hours if you’re just riding along. Instead, Harnish built workouts that would introduce me to what he calls “the entire realm of fatigue.” While I got the express tour of this realm, I still managed to see all of it.

Fuel Like a Pro

➤ You may not have time to train like a pro athlete, but it takes no extra time to eat like one. From the very first long ride of my training plan, Harnish had me striving for at least 60 grams of carbohydrate an hour, mostly from solid foods, which may be less likely than gels to cause gastrointestinal distress when you’re consuming them all day long. In a past life, I tried my nutrition strategy maybe once before the big day. This time, every long ride was also a snack buffet. Sixty grams of carbohydrate is a shocking amount. My favorite granola bar has just 20 grams, which meant I added in fistfuls of dried fruit and chocolate chips to make up the difference.

It felt like I suddenly had a turbo. And, in case you’re wondering: No, I didn’t gain weight. I thought I might—it was just so much food. But when I got home from a well-fueled ride, I noticed another side effect: I did not spend the rest of the day eating everything in sight.

Sleep Is the Ultimate Recovery Tool

➤ Don’t invest significant time in foam rolling, stretching, massage-gun sessions, or wriggling into and out of compression gear. They won’t hurt, but the research simply doesn’t show that they’re worth the precious minutes they take.

What is worth your time? Sleep. If I was regularly cheating myself of sleep to fit in 5 a.m. workouts, Harnish told me point-blank to skip a workout or two and snooze. “Probably the most important recovery tool that nobody uses is sleep,” he says, adding that a missed workout here or there in service of adequate rest wasn’t going to derail my plan.

Know When to Call It

➤ Finally, it’s crucial for athletes with mega-hectic lives to acknowledge their non-training stress. Pressure from life can trigger the same stress hormones we purposefully trigger when we train. “High-intensity exercise after a stressful day can actually compound the stress response,” he says. That means you’ll feel extra sluggish and may need more recovery time.

Harnish’s rule for training when you’re stressed out is this: Try starting the workout. If you don’t feel better a few minutes into the meat of the thing—be it the first interval, or trying to hang on with a hard group ride—then ride easy or call it a day.

In the last couple weeks of training for ORAMM, my marriage—which had long been rocky—went full rockslide. I stopped sleeping. Work that normally took me an hour to do was taking three because I couldn’t focus. That made me fall behind, which added more stress. When I went to ride, I felt like a sack of sad bones bouncing around the trails. So I skipped a few sessions. But because I had consistently worked for the previous 10 weeks, Harnish told me there was “no need to worry.”

Two nights before ORAMM, I packed a bag and moved out of my house. Truly: A mountain bike race was the last thing I needed.

But I’d put in too much work to bail. I drove to North Carolina the next day, feeling completely adrift. A long-time mountain biking friend who lives 1,000 miles away met me at our rental house and held me while I sobbed. And then we got our bikes ready to race.

Truly: A mountain bike race was exactly what I needed.

Me and hundreds of other riders pedaled all day in unrelenting heat. I watched a woman slide off the side of the mountain, and we all dropped our bikes and ran to haul her back up. I lost my confidence on a downhill section harder than anything I ride at home. At a morale low, I talked myself back onto my bike for the final climb and waited for the cramps to set in. But a weird thing happened: I just kept climbing. Around me, men were slugging salt tablets like ravers doing MDMA in a club bathroom. I, however, seemed immune to their fate. It wouldn’t be until the very top of the last climb that my first cramp would set in. By then, it was all downhill to the finish.

I turned my bike onto the last section of hard singletrack and let go of my brakes. I’d finish the race in 9:03, nearly an hour under my goal time. The finish line served as the perfect reminder of my ability to get through hard things. And the work to get there was the perfect reminder that in life and in cycling—sometimes less is more.

3 KEY WORKOUTS

(and why they work)

My weeks were built around these speed, tempo, and endurance workouts. On the days in between, Harnish prescribed an easy hour to stave off detraining—which happens surprisingly fast, he says. This also keeps you in a routine, a useful thing for time-crunched athletes.

1 FIBERTAP

Harnish calls this one “Fibertap” because it taps out both slow- and fast-twitch muscles in under an hour. It became one of my favorites in that hurts so good way.

- 10-minute warmup

- Ride 4 x 2:30 up a hill or in a large gear on a trainer at a 9 out of 10 effort, with an easy spin for 4 minutes between efforts

- 10-minute easy spin

- Complete 2 to 3 all-out 30-second sprints with 4 to 5 minutes of recovery

- 5- to 10-minute cooldown

2 TEMPO REPEATS

Whether you’re prepping for a long gravel ride, a century, or a mountain bike race, there will be times you need to ride at a tough intensity for a significant duration. As my training progressed, we swapped out this workout for Zwift group rides, which added small surges into the mix.

- 10-minute warmup

- 2 x 15 minutes on a flat road at a 7 out of 10 effort, with 4 minutes of easy spinning between

- 5- to 10-minute cooldown

3 HARD THEN EASY

This was the worst/best workout of my entire training cycle. The “hard then easy” name is a misnomer. The easy never really feels that easy. As we got closer to the race, the length of the ride after the intervals increased.

- 10-minute warmup

- Complete 4 x 4 minutes at an 8 to 9 out of 10 effort, preferably on a hill, with 4 minutes of easy spinning between

- Ride 3 to 4 hours at a low intensity, paying particular attention to getting 60 grams of carbohydrate per hour