We were chasing an Edo poet, trying to catch his vibe. In 1684, Matsuo Bashō, the greatest haiku master, walked away from home to wander. He left depressed, lonely, and expecting to die on the medieval highways. Instead, he befriended strangers, embraced the outdoors, and returned renewed. Once a poet that looked inward, his journey through rural Japan turned his focus to the world around him.

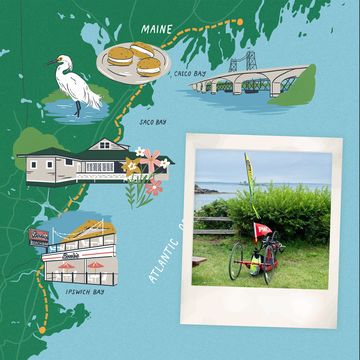

Our adventure had a more humble origin: Joe Cruz and Chris Burati talking big rides over beers at a metal show. Japan was Chris’s idea. He’d studied Japanese literature, and Bashō’s travel and poetry on the landscape stuck with him. Joe, the more experienced bikepacker, charted our route: 800 miles from Tokyo—called Edo when Bashō lived there—to Hiroshima, following his travels when possible. They asked me to join because they knew I’d say yes, and I brought in fellow photographer Parker Feierbach for an even quartet.

We rode 50-pound loaded bikes over mountains, and most nights we camped wherever we found suitable ground: fields, forests, the quiet edge of a city park. We also stopped at onsens, or hot springs, for recovery, and greeted every smiling local we encountered. Once Bashō saw Japan beyond himself, he couldn’t look away, and he couldn’t stop exploring. By the end of our ride, we didn’t want to stop either.

Road Quality

Japan takes care of its roads, all of them. The more remote regions we rode through were covered in logging roads of either single- lane blacktop ribbons or smooth, graded gravel. We felt so far from everything, but we still had roads that had been paved every four or five years.

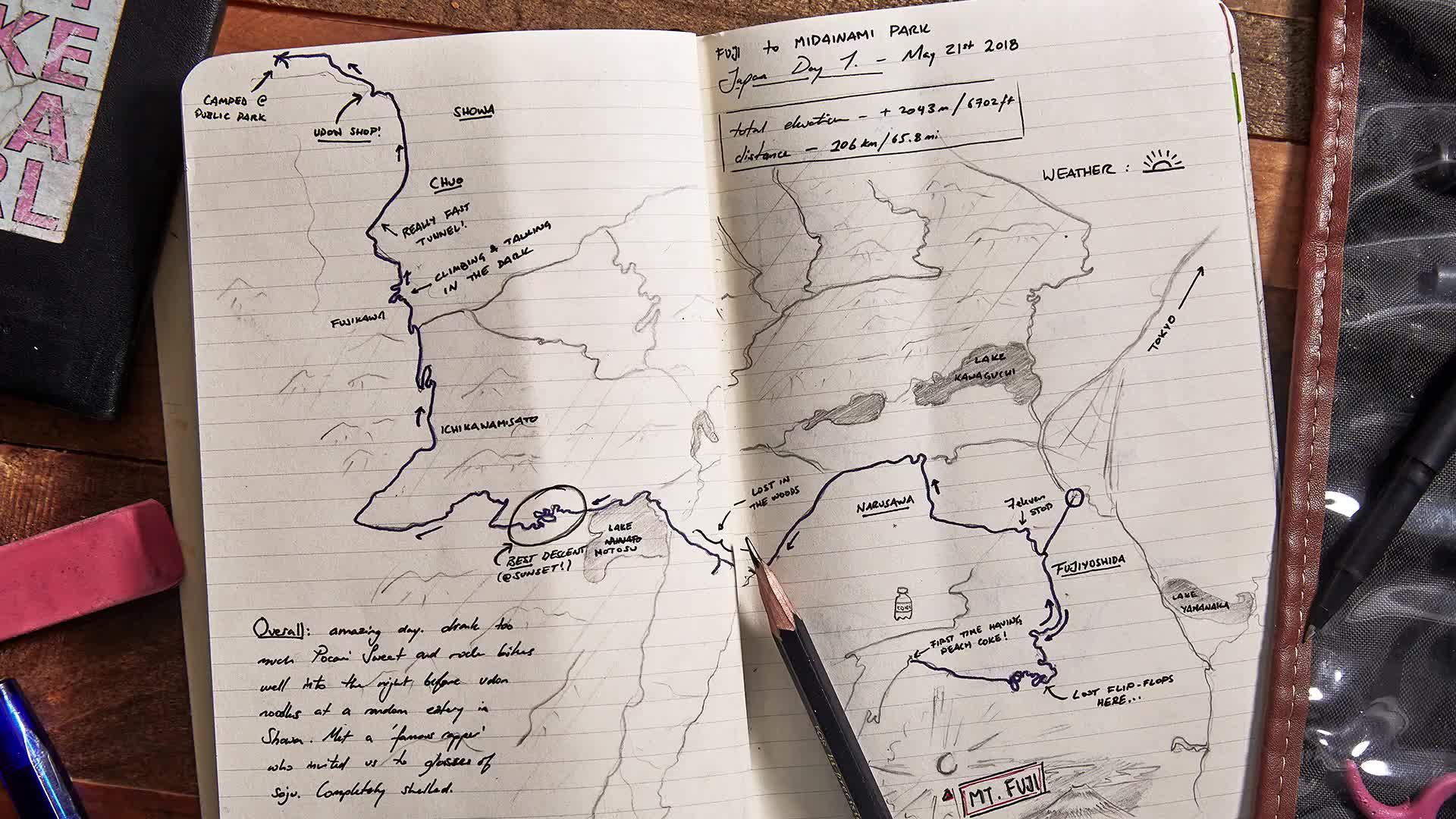

Mount Fuji

After leaving Tokyo by train, we began our first big day in Fujiyoshida at the base of Mount Fuji. Rather, after a mandatory 7-Eleven stop for cans of iced coffee, Pocari Sweat, and packaged pancakes, we began. The climbing started in the town’s quiet streets, and a few miles in we stripped to just bibs under the heat and humidity. We struggled to pedal our loaded bikes in the lowest possible gear, but the dense forest road led to spectacular views of the valley and lakes below Fuji. To avoid the tour vans and cars most cyclists endure, we hopped a gate, ignored the warnings of hikers, and took a single-lane path up to the highest point you can ride on the mountain. Toward the end, the pavement turned to dirt and volcanic ash. After three hours, we reached our summit at the Fujisankomitake Shrine elated, sweaty, and now cold. We had another nine hours of riding before we’d set up camp on the edge of a park, but first we layered up, raised cans of peach Coca-Cola, and descended 4,000 feet back down the quiet lane (almost) without seeing a single car.

Best Japanese Convenience Store Fuel

Japanese convenience stores, konbini, are a wonder of the culinary world. With aisles of elaborately packaged food, you could live off them for weeks. We did.

Hospitality

The kindness and warmth we were met with were unparalleled. Whenever we passed someone, we’d ring our bells and say “ohayo” and they’d say it right back. Locals we stopped to talk with met our sweaty, dirt-covered faces with soft smiles, and gasped in disbelief at the length of our journey. The proprietors of a handmade home goods store welcomed us in with tea and a wood stove to warm up. The owners of a tiny hole-in-the-wall ramen shop in Onomichi kept serving us tall beers and local sake. A bike shop drove out and delivered tubes when we ran low.

And then there was Humi. We had been riding through Japan’s southern Alps, and after skidding and squealing our way down a gravel descent, stopped for dinner at a quiet Swiss-style visitor’s center and restaurant. Humi served our table and walked us through the entire menu, drawing the foods she didn’t know in English. She had questions about our trip and shared her own story—growing up in Kobe but moving to the mountains for the peaceful, open skies. During a formal, surprisingly sad goodbye out in the parking lot, I said I’d be back someday and she jumped in excitement. Our hearts melted.

Tokushima Prefecture

The riding on the east end of Shikoku Island, specifically Tokushima Prefecture, was amazing, remote, and rugged. On day nine, our ride to the night’s onsen, we basically just started going uphill until we were riding above low-hanging clouds. The paved lane, the impressively named Tsurugisan Super Forest Road, was barely wide enough for a truck, and rich, shining green wilderness leaned in on both sides. Finally, the road plateaued and turned to a gravel doubletrack before our 10-mile descent to the hot springs.

The next day we returned to Tsurugisan to keep traveling west. We started in the rain and it never let up. Again we climbed into the clouds and rode a magnificent ridgeline with huge chunks of rocks from the mountain littering the road. We could barely see 10 feet in front of us. It was spooky and cold and windy and beautiful and terrifying all at once. When we reached the top of Mount Tsurugi, we sheltered in a tunnel for a few moments to regroup and made the kind of jokes one makes while wet, frozen, cold, and starving: “Wouldn’t it be amazing if there was a warm restaurant just down the road from us?” No more than two minutes out of the tunnel did we find a mostly abandoned mountain town with a single restaurant open. We piled inside for cups of piping hot tea and bowls of noodles and tall beers. We ended up sleeping in an empty room in a shrine above town to stay warm and dry that evening.

Next Time

A lot of my memories are me thinking a lighter bike would have been really cool—to rip up Mount Fuji or across the Shimanami Kaido, a 44-mile dedicated bike route connecting eight islands. But I’d also try more advanced bikepacking, bringing nutrition so we could go up to four days without services, and get even more remote.

We tried to see as much of the country as we could, which meant a lot of pedaling and debating about whether we were going to stop. My next trip would be more focused on regions, doing a loop in an area for a better feel instead of a straight shot across it. And, of course, I’d have to stop to see Humi. Japan taught me that I want to experience things by bicycle that I’d never expect to see, and meet people I’d never meet otherwise. This is the kind of riding I want to do for the rest of my life.