It’s no longer odd to see disc-brake bikes on a ride—from hardcore roadie world-championship training grinds, to the weekly shop ride, to the townie bar crawl—the brakes that were once only a staple on mountain bikes have become the new standard. WorldTour teams have been riding them during cycling’s biggest races since the UCI approved them for the 2018 season. Heck, even the purists at Bicycling who vehemently resisted discs on aesthetic principle have accepted their excellent stopping power, superior speed modulation, and better all-weather performance on all types of bikes.

What’s even better is that great braking power is now available at almost every price point. And while disc brakes make huge impacts on your ride, they can be heavier and sometimes more challenging to maintain. So whether you’re a holdout or already rocking them, here’s a basic guide to bicycle disc brakes and how to make the most of them.

Types of Disc Brakes for Bikes

There are two main types of disc brakes: mechanical, which works with cables (just like rim brakes), and hydraulic, which replaces the cables with hydraulic fluid in a fully sealed line. When you brake, the pressure forces the fluid to move into the caliper, pressing the pads against the disc.

If you’re interested in buying a disc brake-equipped bike for less than $1,000, you’re probably going to end up with mechanical brakes. This lower-cost option will allow you to spend less and still own a bike with reliable, all-weather stopping power. Apart from price, some riders prefer cable-activated disc brakes because they’re easier to work on at home, and they’re compatible with most mechanical brake levers. But more bikes are coming stock with hydraulic disc brakes. This pricier option is generally more difficult for the home mechanic to maintain.

We suggest having a shop mechanic bleed your brakes (the old hydraulic fluid is flushed and replaced with fresh fluid) because you need to use the right fluid, which is matched to your brake for proper heat management. While this costs more than replacing cables, it only needs to be done every six months. (SRAM recommends bleeding hydraulic disc brakes every six months. Shimano’s official user manuals do not specify a service interval but does say to replace the fluid when it becomes discolored.)

Disc Brake Calipers

Brake levers are attached by the brake lines to calipers located on both the front and rear discs. Calipers contain opposed pistons that sit on either side of the rotor; pressure from the brake line engages these pistons, which push the brake pads inward to contact the disc. The resulting friction slows the bike.

Disc Brake Caliper Maintenance

If your rotor doesn’t spin freely, you know it—the resulting rubbing, grinding, and squealing will drive you nuts—and it can cost you some momentum. Usually, the caliper is misaligned.

Fix this by loosening the two bolts attaching the caliper to the frame or fork just enough so that the caliper can move side-to-side. Wiggle the caliper to make sure it moves freely, then pull the corresponding brake lever hard. This will clamp the caliper to the rotor. Hold the brake lever down to keep the caliper in place while tightening the top and bottom bolts until snug. Then retighten the top bolt to torque spec, followed by the bottom bolt.

See a caliper being adjusted below:

Disc Brake Rotors

Rotors come as small as 140 millimeters in diameter for road and cyclocross applications, all the way up to 205mm for downhill (DH) mountain biking. Generally, road and cyclocross use 140 to 160mm, cross-country (XC) mountain biking uses 160mm, trail riding uses 160 to 180mm (sometimes a mix, with the larger rotor up front), enduro uses 180mm, and DH uses 200 to 205mm. Larger rotors are able to dissipate heat over a larger surface area, but are heavier, so you’ll want the smallest rotor you can get away with for the type of riding you generally do.

Disc Brake Rotor Maintenance

If you’ve adjusted your caliper but still hear rubbing, check your rotor: Sometimes, they warp from a hit or even just excess heat.

“Almost no rotor is perfectly straight,” says Mike Perejmybida of High Wheel Cyclery in Ontario, Canada.

To find out if your rotor is warped, set the bike in a stand or flip it over so the wheel can spin freely. Look between the pads for a wobble, or a gap opening and closing. If you see either, the rotor is out of true.

Often, but not always, warped rotors can simply be bent back using a rotor truing tool like the Jagwire Disc Brake Multi-Tool. Note the section that needs truing, and rotate it away from the caliper. Gently work the tool around the rotor at that section to straighten it. This only works if the rotor is rubbing in one specific spot. If you’re unsure if it’s the rotor or the brake, you’re better off taking your bike to a professional to get it done right. Rotors are strong stoppers, but are fragile side-to-side. “If you do try it yourself, be very gentle,” Perejmybida says.

See a rotor being trued below:

If there are signs of physical damage like gouges or warping that can’t be straightened, it’s time to replace your rotor. Rotors also need to be replaced when the total thickness of the braking surface is less than 1.5mm. If you’ve had your rotor for a while or suspect it’s getting thin, use a set of Vernier calipers to measure, or have your shop do it.

Disc Brake Pads

Brake pads are found inside the calipers. They’re designed to clamp down on the rotor at high speeds, which means their main job (besides stopping your bike) is to hold up under heat and friction.

Resin vs. Sintered Brake Pads

There are two main types of brake pads. Resin brake pads (also called organic) are composed of organic materials like glass, rubber, and fibrous binders bonded together with resin. Sintered brake pads (also known as metallic) are made of metallic grains that are bonded together at high pressure.

In terms of feel, resin pads are quieter and have a stronger sense of bite. They’re better at managing heat, but they can fade as heat builds up. They also wear more quickly, particularly in muddy conditions. Sintered pads are the choice for riders who do mostly steep, lift-served mountain biking. They produce more heat but are less susceptible to its effects; and they last longer under heavy use and in wet conditions.

Resin pads are what most brakes come with, but you should consider switching to metallic if you’re bigger, ride downhill terrain, or ride mostly in wet weather.

Disc Brake Pad Maintenance

If you’ve checked your caliper and rotor but still hear an awful squealing when braking, it can mean that the braking surface (including pads and/or rotors) is contaminated and needs cleaning.

Detach the wheel and use isopropyl alcohol on a clean rag to wipe off the rotor, then remove the pads and clean them as well. It’s also a good idea to wear disposable latex gloves; you’re trying to get dirt and oil off the braking surface, not add more. Make sure to let the pads dry completely before reinstalling.

See disc brake pads get replaced below:

SRAM recommends replacing pads when the total thickness of the backing plate and the pad material is under 3mm. Shimano says that when the pad material alone is less than half a millimeter thick, it needs to be replaced. If you switch pad type (resin to metallic, say), swap your rotors as well; the pads and rotors pair by “bedding” small amounts of the pad material on the rotor, which means an old rotor won’t get optimal performance with a new pad type because it’s already bedded to the other kind of pad material.

Expert Disc Brake Hack

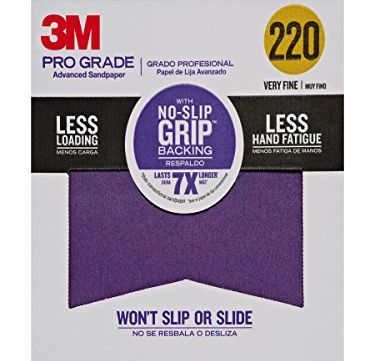

Once you’ve put some big hours in on your disc brake-equipped bike, you’ll start to incrementally wear down the pads and the rotors. If your brakes start to feel less effective, but you’re certain there’s still life left in the pads and that everything is aligned, check to see if the rotors look glossy. If so, it’s time to grab some sandpaper and get to work.

Opt for a minimum of 200-grit sandpaper. Remove your wheels, then gently sand each rotor until the glossy haze disappears, and you see a dull color with a slightly textured finish. With this new texture, your bike’s rotors will provide more friction against the brake pads when you pull the levers, restoring the performance you expect from discs. This inexpensive hack isn’t a cure-all, but it has helped our staff mechanic and logistician, Joël Nankman, extend the life of disc brakes for years. Congrats—you’ve just salvaged the integrity of your brakes.

Joe Lindsey is a longtime freelance journalist who writes about sports and outdoors, health and fitness, and science and tech, especially where the three elements in that Venn diagram overlap.