The single biggest performance improvement you can make on your bike isn’t a lighter set of wheels or fancy electronic shifting. In fact, it isn’t an upgrade at all—and it doesn’t have to cost you more than some time and, maybe, as little as what you’d spend on a new roll of handlebar tape.

It’s bike tire pressure. If you don’t pay attention to inflation, the amount of air in your tires is probably not only not ideal but wrong enough to cause excess flats and serious drop-offs in performance and comfort. Here are our experts’ top tips for finding the perfect bike tire pressure.

Pump it up.

Proper tire pressure lets your bike roll quickly, ride smoothly, and avoid flats. Narrow tires need more air pressure than wide ones: Road tires typically require 80 to 130 psi (pounds per square inch); mountain bike tires, 25 to 35 psi; and hybrid tires, 40 to 70 psi.

To find your ideal pressure, start in the middle of these ranges, then factor in your body weight. The more you weigh, the higher your tire pressure needs to be. For example, if a 165-pound rider uses 100 psi on his road bike, a 200-pound rider should run closer to 120 psi, and a 130-pound rider could get away with 80 psi. Never go above or below the manufacturer’s recommended tire pressures, which are listed on the sidewall.

Check your bike tire pressure regularly.

Tires leak air over time. A properly set up tubeless tire, and tires that use butyl tubes (the most common type), leak far less than lightweight latex tubes. But air seeps out of all tires, from as little as a few psi a week to drastic drops overnight. And the rate of loss increases with pressure and in reaction to outside factors like lower temperatures (about 2 percent vanishes for each 10-degree dip in Fahrenheit). Some of us at Bicycling check out tire pressure before every ride, some once a week. The important thing is to develop and stick to a habit of regular checkups and top-offs that works for you—if you don’t, your pressure is probably wrong most of the time you ride.

And always check the pressure the day after you repair a flat with CO2 canisters. Carbon dioxide is highly soluble in butyl rubber (nitrogen and oxygen, which make up 98 percent of our atmosphere, are far less so), so it basically permeates right through the tube wall, and fast. In fact, if you flat early on in a ride and fix it with CO2, check the tire again after an hour or so—it will probably need topping off.

Find the sweet spot.

Tire pressure isn’t a set-it-and-forget-it thing. Traditional wisdom says that higher tire pressure equals lower rolling resistance, because on a smooth surface, hard tires flex less and create a smaller contact patch. But no road is perfectly smooth. Properly inflated bike tires conform to bumps and absorb shocks. Overinflated bike tires transmit impacts to the rider, which sacrifices speed and riding comfort.

On new pavement, your tires might feel great at 100 psi, but on a rough road, they might roll faster at 90 psi. In wet conditions, you may want to run 10 psi less than usual for improved traction. And if you’re a mountain biker who rides to the trailhead, keep in mind that while your bike rolls smoothly on the road with 40 psi, it might feel better on the singletrack at 30 psi.

Don’t overinflate.

More isn’t always better. The general bias is almost always to overinflate. The maximum pressure listed on the sidewall is generally too high—plus, it doesn’t take into account any factors that influence your tire pressure such as rider size and terrain. Especially if you’ve recently moved to wider tires, are about to embark on a ride full of cornering and switchbacks, or ride surfaces like chip seal, you want to lower your pressure.

While rolling resistance does increase with lower pressure, several studies show that across various road tires, rolling resistance increases only slightly, on the order of a few watts of power, even at pressures down to 60 psi on standard road tires. Then, consider that rolling resistance makes up only a tiny fraction of the forces we have to overcome (most is either wind resistance or, on hills, gravity). The biggest differences in rolling resistance aren’t in pressure, but the actual tire you’re using.

Adjust according to tire volume.

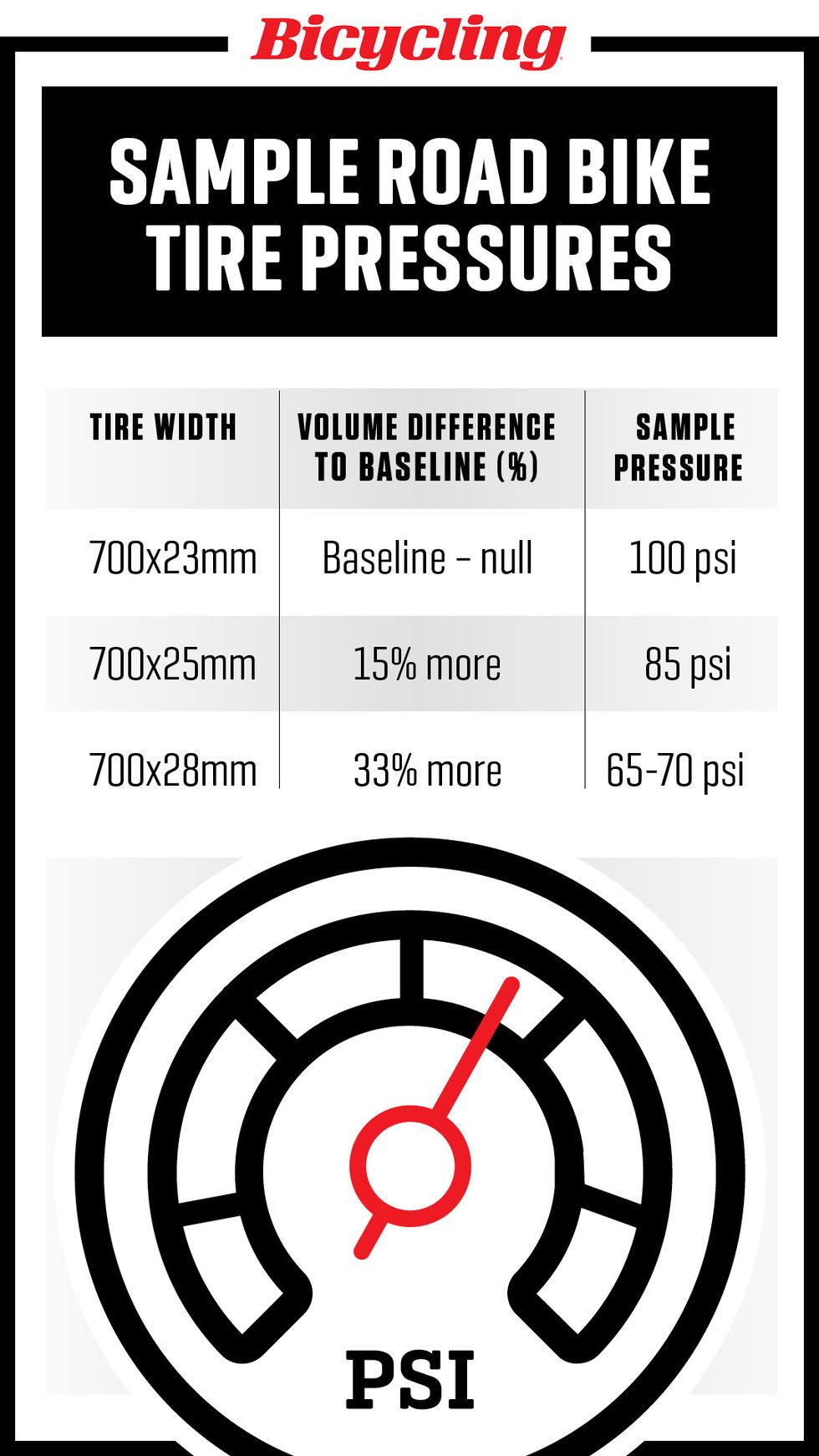

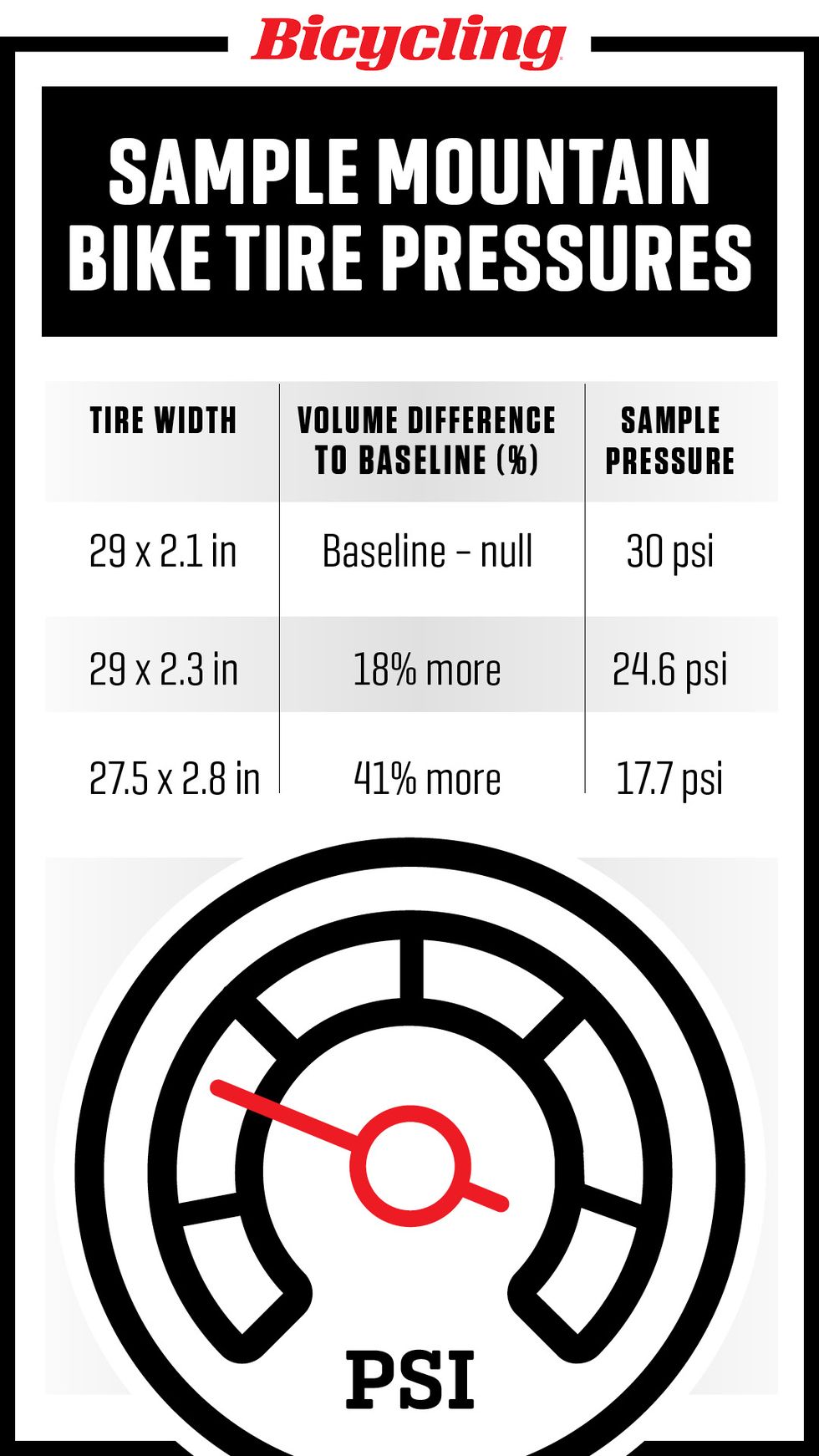

If you’re swapping from a traditional 23mm road clincher to 25mm or 28mm tires, or from a 2.1-inch mountain bike tire to a meatier 2.3-inch, you’re increasing tire volume significantly, so you have to adjust air pressure downward. Here are some sample bike tire pressure charts to consider.

Road Bike Tire Pressure Chart:

Mountain Bike Tire Pressure Chart:

Please note that these sample charts are just guidelines. If you run tubeless, you can scale down even further, about 10 to 20 percent in some cases.

Beware of the floor pump.

If you’re inflating your tires with a floor pump, the gauge is probably not that accurate. Floor pump gauges measure pressure at the gauge, so they’re measuring air pressure inside the pump, not the tire. And gauge quality varies—it may be off by a few psi or as much as 10 to 15 psi.

The good news is that most gauges are at least consistent even if they’re not totally accurate; so at least you’re inflating to the same pressure each time. The fix: Get a separate gauge. A needle-type Presta gauge is simple, affordable, accurate, and durable. Other brands also makes low-psi versions (30 or 15 psi) for use with mountain, cyclocross, and fat bikes for better resolution.

Play with different pressures.

It’s pretty common to simply inflate front and rear tires identically. But your weight balance isn’t 50-50 front to rear. For road riders, it’s more like 40 percent on the front, 60 percent on the rear in most cases, according to a study at the University of Colorado. But it can vary: the study found a range from 33-67 to 45-55 across the athletes they tested.

This means whatever pressure you prefer is going to depend on a variety of things including your tire choice and riding style, but it’s also clear that you shouldn’t run the same pressure front and rear. If you weigh 150 pounds with a 40-60 weight distribution, that’s 90 pounds on the back wheel and 60 on the front. So it stands to reason that you should be running proportionately less pressure up front. It won’t be 50 percent less, but it’s not unreasonable to think it could be 15 to 20 percent less.

Experiment with tire pressure by deflating front and rear, say, 5 percent each (percent, not PSI, because remember, front and rear are different and should be changed proportionately). Go ride and take note of how it feels, and don’t be afraid to drop a little more. Ideal tire pressure gives you a comfortable ride with a confident feeling in corners. Once the front wheel starts to feel the least bit squirmy in hard cornering, add a few psi back in. Measure front and rear with your gauge and write it down as a baseline, but remember—the perfect pressure may change according to conditions, terrain, weather, and if you switch tire sizes or brands.