It was just a flick of the elbow. Pull through.

Sepp Kuss, the talented American climber on Jumbo-Visma, was on the attack during the final stage of the 2020 Critérium du Dauphiné, and Tadej Pogačar, the even more talented Slovenian all-arounder on UAE Team Emirates, was covering his move. Flick went Kuss’s elbow, accompanied by a quick over-the-shoulder glance. The message of a flick is simple enough, but it often carries subtext. Pull through if you can. Pull through if you dare. Pull through, asshole, and do your work. But that day, the subtext was something else, an acknowledgement and respect, a sign of the fireworks we’d see in a month.

Pogačar pulled through with a bobbing nod, but the pair were quickly recaught by a two-man chase. The ferocious attacks, counterattacks, and attrition marked an unusually aggressive final stage, even by Dauphiné standards, of an unusual race in a most unusual year. So Kuss slipped back into the small group with eventual GC winner Daniel Martinez of EF Pro Cycling, soft-pedaled a couple of strokes, took a drink, and thought about his next move. He wasn’t even supposed to be in this position.

Oh, sure, Kuss was supposed to be here, at the front of the race. But he was supposed to be shepherding Jumbo’s captain and the race leader, Primož Roglič, to an orderly win. The Dauphiné, normally a key tune-up race for the Tour de France, seemed more fraught with meaning in a pandemic-scrambled 2020 season that saw the Tour delayed until September. The Dauphiné was just the second WorldTour stage race since March’s Paris-Nice, and the Tour was just two weeks away. Nobody knew what anyone’s form looked like, which is what the Dauphiné was supposed to help settle: Where did the star riders stack up in the WorldTour pecking order?

Roglič won Stage 2 to take the GC lead, widened the gap to second on Stage 3, and appeared poised to defend it through the final two days. Then Jumbo’s race went pear-shaped on Stage 4. First, Steven Kruijswijk, a key lieutenant and top GC rider himself for Jumbo, crashed out hard on an early descent. At the midpoint of the stage, Roglič went down too. He got up, jersey and shorts torn and bloodied, and under the watchful eye of Kuss and teammate Tom Dumoulin, managed to rejoin the group and finish with the leaders. But the team decided not to push its luck and scratched him from the final stage, an arduous, eight-climb affair. “The evolution of his injuries will determine the plans for the upcoming races,” the team said in a terse tweet that conspicuously avoided mentioning that Roglič’s only upcoming race was the Tour.

In the span of 24 hours, Jumbo went from commanding a prestigious and vital pre-Tour event to losing two top riders to injury and throwing its Tour de France plans into jeopardy. The team needed a comeback, and it was Kuss—not former Giro d’Italia winner Dumoulin—who delivered. On Stage 5, Jumbo forced the pace from the start, whittling the field to an elite group of around 20, including 2019 Tour revelation Julian Alaphilippe, former Tour podium finisher Romain Bardet, and, of course, Kuss and Pogačar. As the attacks continued, Kuss calmly made the selection at every point even as top contenders like Mikel Landa cracked and Thibaut Pinot spiked his water bottle in frustration at getting dropped. Kuss’s first attack neutralized, he sat patiently in the dwindling group and waited for his moment.

That opening came at the base of the final climb, a nine-kilometer stair-step ascent with a finishing ramp on an alpine airport runway, the kind that’s set on a slope to aid takeoffs and landings because it’s ringed by mountains. Kuss timed his move perfectly, pouncing just as an attack by Ineos’s Pavel Sivakov was hauled back, and this time not even Pogačar followed. After a furious 18 minutes of alternatively stomping his pedals and time-trialing from the drops, Kuss crossed the line first, 27 seconds up on Martinez and 30 ahead of Pogačar.

The Dauphiné stage win was a tantalizing result, yet another confirmation of Kuss’s formidable climbing talent, previously seen in his stage win at the 2019 Vuelta España and his dominating ride at the 2018 Tour of Utah. “That Dauphiné gave me confidence that I could be there against some of the best,” said Kuss when we hopped on a FaceTime interview this past May. And on a team that usually has him riding for others, he added, “it gave me a sense of how nice it is to win.”

The next logical step for the 26-year-old Colorado native is an opportunity to lead the team at a Grand Tour himself. That might come as soon as this fall’s Vuelta, after his usual role at the Tour backing others (where he and the team have salvaged impressive results despite Roglič’s DNF). “We see in Sepp a rider who can lead our team in a Grand Tour, and that moment can come quicker than expected,” says Mathieu Heijboer, his coach at Jumbo. But it’s a big jump from riding to a high finish in service of another rider to fighting for a podium yourself. And among those who question whether or not Sepp Kuss can make that leap is Kuss himself.

In a May 2020 interview with Procycling, he said, “right now, I can’t imagine myself being a Grand Tour contender.” It’s a remarkable admission of self-doubt in a sport whose athletes aren’t known for that kind of open reflection.

But then came the Tour, where he again went wheel-to-wheel with Pogačar through the Alps, and the Vuelta barely a month later, where he helped Roglič win. Kuss finished well inside the top 20 both times, results that hint that something far greater is possible. I wanted to know: Had those rides changed his view? “It’s not like a block, not something that I don’t want to do…” he began to explain. But he was hedging, speaking so carefully that he used a double negative to distance himself from the notion. Does Sepp Kuss want a shot at a Grand Tour, or not?

It would be easy to view Kuss’s rise to the WorldTour as a tale of destiny: an athlete built for racing, with the innate gifts to excel in the world’s hardest races. Kuss was born and raised in Durango, the son of endurance athletes and prominent members of Durango’s hard-core outdoor community. He’s an alumni of Durango Devo, the renowned junior mountain bike program that has produced such athletes as Olympian Chris Blevins and fellow WorldTour roadie Quinn Simmons.

Kuss won three national collegiate mountain bike titles at the University of Colorado Boulder. There he dabbled briefly in road racing until 2016, when he won a stage of the Redlands Classic against a top domestic field and scored a pro contract with highly regarded Rally Racing; by the end of that season he was riding for the U.S. national team in Europe. A standout ride at the 2017 Tour of California drew the notice of top European teams. On his superlative climbing and dirt-honed handling skills, he went from amateur roadie to the WorldTour in under three years.

That’s the condensed, conventional version of Sepp Kuss’s rise, the one that treats his path to his current station in life as a series of inevitabilities. But the tale of that arc also leads to a question with no obvious answer: Why, given Kuss’s path, would he not wholeheartedly, instantly, with zero reservations, embrace the idea of team leadership?

Put another way: What young American bike racer of Kuss’s talent would not say, “Yes, my dream is to one day win the Tour de France,” the only race most Americans even care about? But Kuss does not say that. And to understand why, you have to understand that his path to this point was far from a sure thing. That he’s here by a series of choices that were deliberate and considered, if the circumstances are still serendipitous. Sepp Kuss is where he is because he’s thought—deeply—about every step he’s taken. He is where he is because he’s still thinking about the steps to come.

The steps started early, and small. Kuss’s first love was hockey, says his mother, Sabina, and like all children, he had dreams of being a pro. His slight frame (he’s 135 pounds even today) made that impossible. Fortunately, he had other options.

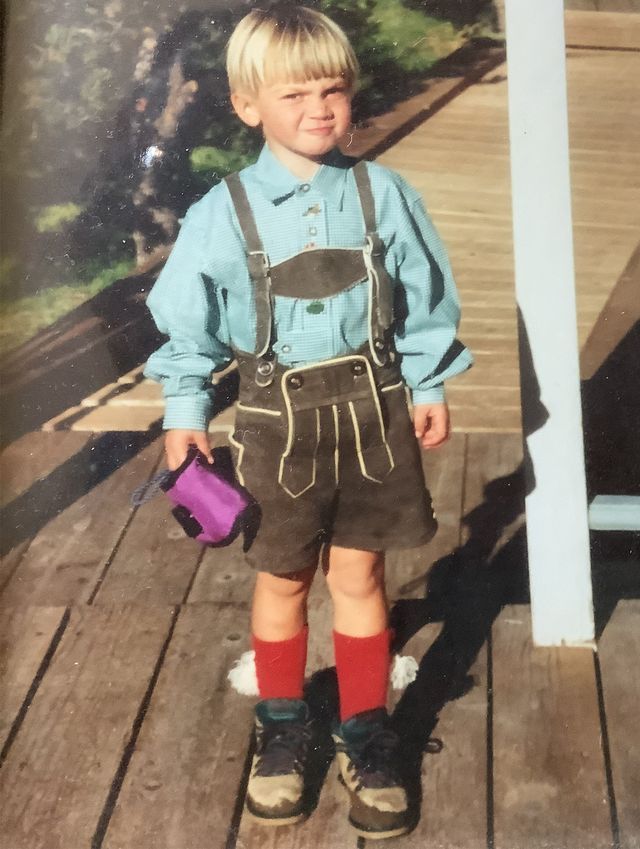

“Our way of life is sports participation,” says his father, Dolph, and from an early age, Sepp excelled at trail running, whitewater kayaking, skiing, and anything outdoors. Sepp was also steeped in a blend of German and American mountain cultures. Sabina, whose mother had emigrated from Germany, fell in love with mountaineering when she spent a year in Austria. (While there, she picked up the name Sepp from local climbers, and liked it enough to use the name on a pet goat before her son was born.)

As an infant and toddler, Sepp (the human) regularly accompanied Dolph and Sabina on weeklong burro pack trips in the rugged San Juan mountains around Durango. “Seppy never knew anything different” than life in the outdoors, Sabina says. Those trips were also their first encounter with his decisive, self-confident nature. As soon as Sepp was able to take more than a few steps on his own, Sabina recalls, “he didn’t want to ride [the burro] anymore. He wanted to go on his own.”

Despite their impressive backgrounds, Dolph and Sabina didn’t push Sepp. Dolph is a former U.S. Ski Team coach and played an instrumental role in Durango’s development as an outdoor capital. A professor of exercise science at Fort Lewis College, he founded the school’s treasured Outdoor Pursuits program and built the rope tow on Chapman Hill, Durango’s in-town ski area. He’s also in the Colorado Ski Hall of Fame. Sabina teaches Nordic skiing and is an accomplished whitewater kayaker.

“We just introduced him to things that were close to our heart,” says Sabina. And Sepp had little trouble asserting his independence. One day, when Sepp was in fifth grade, Sabina recalls, he came to her and said he didn’t want to do the river trips anymore. In summer, he said, he liked mountain biking best.

So Dolph and Sabina enrolled him in Durango Devo’s first class of riders. “He was a coachable little guy,” recalls Devo cofounder Chad Cheeney, but not the best rider on the team. Maybe that had to do with his teammates—like Howard Grotts, who went to the Olympics twice, and Stephan Davoust, who’s now a top domestic pro for Giant Factory Off-Road. But it might also have been Devo’s approach to the sport, which began long before the club got a rep for developing champions. Instead of the tight training focus that marks some junior programs, Cheeney and cofounder Sarah Tescher emphasized games and adventure rides, says Davoust. “You thought you were just racing friends to stop signs, but you were doing sneaky interval training,” he says.

That attitude fit Kuss perfectly. He was never motivated by results or rankings. What mattered to him about mountain biking was exploring; he’d go out regularly for six-hour adventures, Dolph recalls. And what mattered to him about Devo was the fun and camaraderie. Even in races, says Cheeney, Kuss would sometimes stop to help fellow racers on course if they had a mechanical.

Still, Kuss’s talent was evident, and he could have easily followed in the family footsteps to Fort Lewis and its powerhouse collegiate mountain bike program. But one day, Sabina recalls, he sat her and Dolph down to tell them that he’d decided to move to the other side of the Rockies and attend the University of Colorado Boulder. While Kuss joined CU’s club cycling team, racing had little to do with his choice of universities. “I love Durango, but it’s a small town,” he says. “I wanted to meet different people and see what else was out there besides cycling.”

Sometimes, what else is out there is just a different kind of cycling. In Boulder, Kuss and his roommates discovered the Thursday Night Cruiser Ride, a warm-season tradition that brings out the town’s looser two-wheeled side. (For years, the ride would end at the Rio Grande restaurant downtown, where patrons are limited to three of its famously potent margaritas.)

Kuss liked the ride’s party vibe, especially the costume theme, which extended to the bikes themselves: At its peak, the ride had a couple of hundred riders who rode everything from elaborately constructed tall bikes to bakfiets decorated like pirate ships, all meandering along Boulder’s streets and multiuse paths while music blared from portable speakers. Josh Gallen, his roommate for four of Kuss’s five years in Boulder, recalls regular trips to thrift shops where they’d buy kitschy shirts, vintage suits, wigs, anything to add to their massive collection of random costume items for the ride. “Sepp doesn’t really do anything in moderation,” says Gallen. “He’s the fastest guy on the bike and then he’ll out-party you the same night.”

While he was winning his three collegiate titles, Kuss was also exploring Boulder’s deep road scene. On training rides, he began claiming Strava KOMs held by top local pros, like Taylor Phinney and Tom Danielson. Kuss likes KOMs, that’s clear; his profile lists more than 60 pages of them, many from his time in Boulder. But he wasn’t hunting just to hunt. He was also using Strava to look for new routes and adventures, six-hour odysseys he’d do—often solo—finding climbs he’d never ridden before.

In Boulder, Gallen recalls, Kuss spent hours on the site, piecing together routes and looking up climbs, “and then he’d get up the next day, go do the ride and come back with all these KOMs.” A classic example of Kuss’s affinity for perversely difficult routes not suited to KOM bagging is a 2014 ride he titled “ooo kill ’em!” On his Strava profile, the route map shows a seven-hour, six-tentacled beast of out-and-back climbs around Boulder totaling 92 miles and 15,000-plus feet of climbing. He still notched a second-place time on the nearly 10 percent gradient Magnolia Road climb—in January, and which still stands seven years and thousands of attempts later—and took a KOM on the fifth of six major climbs that day, which also still stands. By the end of his freshman year, says Gallen, Kuss was going on rides with “all the fast dudes” whose KOMs he was taking.

Encouraged, Kuss decided to explore road racing more. In spring 2016 he joined a small amateur development team sponsored by a Harley-Davidson dealer to race the Redlands Classic, where he surprised the field by winning the hilly Oak Glen stage over a field of top domestic pros.

Jonas Carney noticed. Carney is the performance manager for Rally Cycling, which races one level below the WorldTour, and he’s always on the lookout for prodigies. While not specifically a development team, Rally has nonetheless sent a number of North Americans to the WorldTour, including Michael “Rusty” Woods and Brandon McNulty. “A lot of times you’ll find climbers who just can’t ride their bikes very well,” says Carney of the hunt for hidden talent, but Kuss’s off-road handling skills meant he was already comfortable in the pack. Kuss signed with Rally in late May; in his first stage race with the team, Canada’s Tour de Beauce, he struck again, winning a climbing stage and finishing sixth overall. By late summer he was finishing his first season on the road, racing in Europe for the U.S. national team at the prestigious Tour de l’Avenir, the Tour de France for young riders.

Still, Kuss didn’t think seriously about a pro career. He was rarely riding more than 15 hours a week, still focusing on school, and mindful that the term “pro cyclist” is pretty loosely defined. “If I was going to do it, I wanted to make an actual living, not just get by,” he says. Even as he continued racing full time for Rally in 2017, he graduated with a degree in advertising.

It wasn’t until the 2017 Tour of California that “making an actual living” became a clear possibility. Rally won two stages, but it was Kuss’s 10th-place finish on the grueling Mount Baldy stage that turned heads. He finished just behind Robert Gesink, one of the top climbers on what was then the LottoNL-Jumbo team. LottoNL management noticed, and by that fall his contract was inked: Kuss was headed to the WorldTour.

Carney thought he jumped too soon. Kuss was just so green. “Europe is a shock to the system,” he says, and he knew Kuss had barely 25 days of racing on the continent under his belt. Unlike on wide American roads, European racing is “a fight to even be close to the front before the climbing starts, and that was Sepp’s learning curve,” says Carney. There’s also the cultural shift, says Christian Vande Velde, a former pro who’s now a commentator with NBC Sports. “It’s tough to be over there training in February when it’s raining and you don’t even know how to get groceries,” he says.

But Kuss was not naive; he’d traveled internationally as a kid, including to Europe to see family, and spent months in preschool in a small village in Chile’s Lake District, where Sabina had done a teaching sabbatical. So it wasn’t as if he was unfamiliar with other cultures. But from a racing standpoint, he knew that if he went to Europe unprepared, he wouldn’t have survived. That’s why he signed with Rally to begin with. “I didn’t want to do all the work and go to Europe and get my teeth kicked in every day and take a step backward,” he says.

He got his teeth kicked in anyway. Kuss’s first spring in Europe in 2018 was quiet and hard. He struggled with big packs on small roads, and his early results—in sharp-elbowed fields at sharp-profiled stage races like the Volta ao Algarve and Itzulia Basque Country—were anonymous finishes or DNFs. Carney watched, still concerned that it was too much, too soon. But Heijboer and Jumbo had expected the struggles, and remained patient. Kuss climbed his learning curve, and by the 2018 Dauphiné, just before a break for a trip home to the U.S., he wasn’t fighting just to survive anymore.

And yet his next big step up came back in North America. Kuss went to the Tour of Utah that August with good form, but no one really knew how good. On Stage 2, a bold attack from 50 kilometers out netted him the stage win and a narrow lead over BMC’s Tejay van Garderen and a stacked team from EF-Cannondale. Kuss ably defended the next two days, but a major challenge loomed in the Stage 5 finish atop the steep Snowbird climb, and Kuss faced threats from no fewer than four teams with riders in striking distance. He left nothing to chance.

Gallen, the roommate who rode with Kuss almost every day for four years, recognized it before it happened. “I’m watching him on TV at the front, and at the bottom of the [Snowbird] climb, he took his glasses off and took his gloves off,” he says. “I was like, ‘Oh, he’s about to go big.’” After soloing to the win and positively thumping the other climbers, Kuss added even more insurance on the final stage by going off the front again, taking his third win in five days and a dominating overall victory. That performance led to his first Grand Tour start, in the Vuelta a España that fall, and put him on Jumbo’s A team for the three-week races. Since then, he’s been on every Grand Tour team with Roglič, and even won a stage of the 2019 Vuelta. “He progressed faster than anyone else [I’ve seen],” says Carney. “Obviously, he proved me wrong.”

Despite all that promise and self-evident talent, Kuss has finished in the top 10 in European stage races just twice. What holds him back? While Carney credits Kuss’s progression, his former protégé’s craft is far from flawless. Kuss’s biggest weakness is the time trial. For one thing, he hasn’t had much experience. “I need more actual TTs,” Kuss admits. “It’s hard to replicate that in training.”

And no amount of training will settle some immutable math and physics. On climbs, Kuss has the goods: the magical six watts per kilogram of functional threshold power that is the mark of a potential Grand Tour winner. But in time trials, total power matters more, because aerodynamics, not gravity, is the primary obstacle. Aero drag is largely down to the athlete’s position, and the cruel truth is that shorter, lighter riders put out less total power than big ones but don’t have proportionately lower drag.

Current world time trial champion Filippo Ganna, for instance, at 45 pounds heavier and six inches taller than Kuss, produces roughly 100 more watts at threshold but has an exceptionally efficient position. That’s not to say Kuss is hopeless; he turned in a surprisingly solid result at the prologue at the Tour of Romandie in April, and a respectable 33rd at this Tour’s first time trial. But his prowess is never going to match up to that of teammates like Roglič, much less specialists of the discipline. He needs a course suited to him: lots of mountaintop finishes, light on TTs.

The second major issue is one over which Kuss has arguably even less control. While being on a team like Jumbo that’s stacked with talent means there isn’t much pressure on Kuss to deliver a big result, it’s a problem if Kuss wants to lead. He recently re-signed with Jumbo through 2024, when he’ll turn 30; that gives him security, but it also locks in what will likely be his most productive racing years.

The team’s top rider, unquestionably, is 31-year-old Roglič. Its likely No. 2 is former Giro d’Italia winner Tom Dumoulin, who is 30. Kuss would seem to be option 3, but Jumbo is also excellent at identifying and developing young riders.

And there is a pair of fast-rising all-rounders behind him: Jonas Vingegaard, who was second to Roglič at April’s grueling Itzulia stage race and is turning into this Tour’s revelation, currently in third overall; and Tobias Foss, who quietly rode to an impressive ninth-place finish at the Giro in just his second Grand Tour. Both are 24. You get the sense that if Kuss doesn’t deliver some significant GC results of his own soon, he’s going to forever be a wingman, the guy behind the guy.

But the biggest obstacle to Kuss’s progression and development into a team leader and Grand Tour contender isn’t some simple problem of physical abilities. On the right course, Kuss is as much a threat as any other climber-GC guys who’ve found a way to succeed. And it isn’t his team, either; Kuss is being given chances to lead, and will be given more. The biggest question, honestly, is something far more basic: Does Sepp Kuss really want to be a leader?

He insists that yes, he is looking for leadership opportunities at Jumbo; he’s just not sure where. “It’s hard to say what I want, because there are so many races that suit my skill set,” he says. And he’s had a few shots this year already, although his performance in those races has been uneven. But if he feels pressure to make it happen right away, he’s not showing it. And his ambivalence raises a different concern: Are the questions about Sepp Kuss’s future as a racer more about his hopes, or ours?

The peloton is packed with guys who spent chunks of their careers trying to be riders they weren’t. Guys who tried to be Grand Tour champions when a focus on climbing and weeklong stage races might’ve suited them better. Guys who burned out their engines trying to transform themselves into Monuments Men, specialists at 250K and longer distances, when hunting stages and shorter one-day races might’ve been a far more rewarding endeavor. And guys who rode to top-15 finishes in Grand Tours while supporting teammates, only to freeze up when given their own chance to race for the win.

Heijboer, Kuss’s coach at Jumbo, says one of Kuss’s biggest assets is mental strength. “He’s never stressed or uncomfortable with expectations,” he says. But Vande Velde notes that there’s a different pressure in leadership than as a support rider, and he should know: He rode 22 Grand Tours, mostly in support of others, but shouldered the leader role in 2008 when he finished just one spot off the podium at the Tour de France while captaining Slipstream-Chipotle, then an extremely green wild-card team.

To Vande Velde, Kuss’s 2020 Dauphine stage win shows his potential. “It’s so hard to just completely change the chip in your head from looking out for someone else and then trying to get a win for yourself,” he says. “For him to win with only one day of thinking about it, that was impressive.” On the other hand, it was just for one day, and then the race was over. As Kuss himself notes, it’s another thing entirely to deal with that for three weeks straight. “Having that focus every day, it’s really hard mentally to do that,” he says. “Getting used to being in that frame, being in the right position all the time, is pretty draining.”

But maybe the reason Kuss never seems stressed is that he has a sense of himself; he knows where he best fits. When you talk to people about Kuss, the picture that emerges is of a person Gallen calls “a super, super nice and friendly guy.” As a college housemate, Gallen recalls, Kuss was “tidy and conscientious,” not qualities young guys are known for. He’d wake up early in the morning on a weekend, make a pot of ridiculously strong coffee, and spend the day cleaning the friends’ shared garage and tuning everyone’s bikes. As a child, Sabina recalls, Sepp had none of the natural self-centeredness that’s so common to very young kids. “When we went on a vacation, he would say, ‘What would you like to do, mama?’ or, ‘Which mountain do you want to climb?’ He’d always put it to us instead of being the leader,” she says. Despite his age, Sepp is, as she puts it, an old soul.

And when Carney was scouting Kuss as a possible fit for Rally, he contacted close friends in Durango for a character check before he offered a contract. The reviews came back glowing, and Carney says Kuss had an outsize impact on the team even in his short time there, “a really positive influence and just a great kid to work with.” Maybe Kuss isn’t pressing on the leadership thing because he really doesn’t feel a sense of urgency; he trusts that things will unfold as they should.

Vande Velde notes that Kuss is adept in a support role. “I think it’s his natural being; he really embraces that and does his job,” he says. It fits with Kuss’s easy nature, his conscientious mentality. And financially, a top équipier like Kuss can pull down as much as $1 million a year. A mil! To wear stretchy pants and ride a bicycle fast?! Young Sepp Kuss would never have dreamed of it.

“It’s really nice to be a helper,” he says. “That’s a big goal—when you ride for riders who are winning almost every race.” But, he adds, “It’s also really motivating to be in a position to win a race, to get a result for yourself.”

One such position happened on Stage 15 of this year’s Tour, one of the hardest. It crossed the race’s high point at the 2,408-meter Port d’Envalira before ending in Andorra, Kuss’s home in Europe. Emboldened on home roads, Kuss was one of the first riders to animate the early attacks, eventually joining a group of more than 30 riders ahead of an uninterested peloton led by Pogačar’s team.

On the final climb, the Col de Beixalis, baking in the late-afternoon heat, the break turned on itself, as it always does, with riders probing with attacks and counters, chasing and feinting to test their rivals. Midway up the climb, Kuss had seen enough and launched a ferocious attack that none could follow. One tried: Alejandro Valverde, the wily Spanish veteran still going strong in his 20th pro season.

As Valverde chased, Kuss’s directors coached him through the finale. “Now the real steep part is coming,” said Frans Maassen over the radio link to Kuss’s earpiece, “2.5K, really steep.” Over the summit, with just 15 kilometers of narrow, technical downhill to race, Kuss got another update: “It’s only Valverde on 25 seconds. The rest are gone.”

Ordinarily, experience would favor Valverde, who was riding his 14th Tour. But Kuss had just passed his home in Soldeu, Andorra; although he said post-stage that the Beixalis is hard enough that it’s not a common training fixture for him, he still knew the 11 switchbacks on the descent, where they tighten and how to maintain speed through their curves. “Twenty seconds, Sepp, 20 seconds,” came Maassen’s report over the radio. “Come on man! You’re flying. Come on!”

There would be no catching Sepp Kuss. Solo across the line, he joyously flicked his sunglasses to the crowd, exhaled a breath he might have held for the entire descent, and covered his eyes as if in disbelief.

“I still cannot believe I am in the Tour de France, much less winning a stage,” he said after the finish. “It’s really incredible; I’m lost for words.” Kuss noted that the team is split between objectives. “We want to go for stages, and we have Jonas, who is riding so strong.” He wanted to finish the day’s job with a stage win, he said, but added, “From here on out I will be supporting Jonas.”

Leader one day, helper the next. But athletes’ careers often have breakthrough moments, where a long plateau is suddenly broken with a steep ascent to a new level. And winning a stage of the Tour—Kuss’s finest victory yet—is definitely another plane.

With every race he does, he gets a little more used to that pressure. “When I do go to that mindset, it’s easier for me to stay out of trouble and be in front,” he said when we talked in May. Every top result he gets is another taste of success. He’s still circumspect about Grand Tour ambitions. “It would be good to try for that and at least give it a shot and see where my skills are,” he says mildly of the idea of Grand Tour leadership. He will not be pushed. Sepp Kuss is going to be the best damned Sepp Kuss he can be. What that is, he may not even know. But finding out will be his biggest adventure yet.