Biddeford Pool is everything a tiny Maine seaside village should be. An ice cream scoop of land dangling in the cold blue Atlantic. Hand-painted mailboxes. Only one road in and out, the town beach an undulating swath of sand with ocean on one side and the Pool, a body of tidal saltwater surrounded by marsh grasses and sing-songing birds on the other.

“Have you arrived?” my friend Jan texted. Biddeford Pool, at 4 p.m. on day two of our four-day, 200-mile summer of 2021 bike tour through Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine was the one immovable deadline on the trip. The long-delayed memorial service for Jan’s husband Andy was to begin in a half hour. We had started early some 55 miles ago back in Rye, New Hampshire, and we were close.

We were soaking wet from a day’s worth of rains and the only place to change when we got to Biddeford Pool was a porta potty next to the picnic tables outside Pool Lobster at Goldthwaite’s. For a tired cyclist trying to throw around partially paralyzed legs it wasn’t pretty. Twenty minutes along, with urine fumes assuming critical mass, I was leaning over to tie my shoes when I lost balance and tumbled out the unlocked plastic door.

Embarrassment, sure.

But I was graced with an unimpeded view over the western tip of land to the bay’s Monument Island. The day was brightening.

My legs—good for thousands of cycling miles and adventures over four decades—had become partially paralyzed during a radical cancer surgery in 2014. The large tumor, a rare sarcoma called chordoma, encompassed my left hip and lower lumbar spine. The surgery saved my life, but the complication colored the result, the severity of it unclear until almost a year later after a battery of tests. In 2019, a stroke after another back surgery caused more leg damage.

From the beginning, my physical struggles were defined by a quest: Could I ride a bike again? I had a spine made mostly of metal rods and fused transplanted bone. Challenges abounded: legs with little power, dropped feet, hips that couldn’t raise either limb to clear a standard stair riser, much less a top tube.

My intent was to ride upright, like I used to. I first tried a pedal-assist step-thru e-bike, with a dropper post to aid getting on and off and clipless pedals to keep my feet from sliding off. Next came a beautiful, borrowed tandem. One summer day my son Henry and I rode it on some of my old routes in eastern Massachusetts, reminding me over 75 spectacular miles what I loved and what I missed.

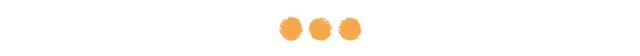

But being the stoker, and contributing little stoking at that, led to my first serious consideration of an adaptive hand pedal bike. When I tried a lay-down, luge-like race model at an adaptive sports center in New Hampshire, I admitted it wasn’t half bad. I was back in control, steering and shifting, going surprisingly fast. In 2020 I rode 2,000 miles on a rental, then at the end of the year I bought a used Top End Force RX race machine with aero wheels from a guy named Joey in Phoenix. He promised I would love it.

You know a cycling trip is real when t shirts are made. “RATBOi 2021” ours said, white cotton, hand lettered in marker, sort of like the “Cutters” ones in Breaking Away. The acronym stood for Ride Across Three Borders of Interest. Admittedly a bit vague, but I was looking for something that sounded like RAGBRAI, the iconic 7-day annual ride across Iowa I had originally signed up to do in 2021.

I was turning 60 in June, reason to try something I’ve never done that was well above my punching weight. I scanned the cycling horizon for a suitable challenge, considering everything from the nearly 300-mile Alaska Challenge to Norway’s Styrkeprøven, a roughly 340-mile gran fondo with a 32-hour time cutoff. These ideas were madness, but you can see what I was thinking. (Styrkeprøven translates to “Great Trial of Strength,” which might explain why the organizers never returned my email.) Ultimately, I learned the former was no longer and the latter a last-minute scratch in 2021 because of Covid.

RAGBRAI it was. Then it wasn’t. My wife Patty, justly, had rethought her summer “vacation” driving support across the lonely width of Iowa and worrying about me surviving (again) for seven long days.

After we scuttled those plans, my brother Tom wondered if I had thought about something local, maybe up the New England coast for three or four days. Maybe he would join me. We could start at my home in Beverly, a suburb of Boston on the North Shore, cross briefly through Massachusetts and New Hampshire to Maine, and perhaps pick up lapsed cycling friends along the way.

I had imagined my 60th to be about a singular individual test. I thought I was going to race someone or something. This was different. Different idea, different mood, different challenges. A part of my former identity was impulsively jumping into a cycling adventure and figuring it out later. This new idea had just enough of that. The final destination would be Westport Island in mid-coast Maine, about 50 miles north of Portland, where my friend Neil had a house. He promised fresh oysters, which were currently submerged in tidal water steps from his backyard.

RATBOi was born.

The start list from my driveway in Beverly, besides Neil and Tom, included guest riders Mike and Chris. Both were old friends who had been on the longest bike ride of my life, a hilly 150-mile daylong marathon from Westford, Massachusetts, to a 4th of July cookout in Vermont’s Green Mountains.

This day, I promised, would not be that day. I was “pedaling” with my arms, I reminded them. But my track record for unnecessarily leading others to extreme physical discomfort dated back decades. I was aware, and kind of pleased, that nobody quite trusted me.

At the time, I was nervous overseeing our route, unsettled with my trike setup plans. I’d never carried anything with me on the bike except a CO2 cartridge and a spare tube. In the weeks leading up to RATBOi I practiced roadside “dismounts” for nature breaks and flat repair with mixed success. I decided not to spend a small fortune in customized trike bags and instead used a kayaking dry bag looped over my seat to carry clothes, adding a hydration pack to stuff with tubes, tools, and snacks. A half-filled bladder, if positioned just so, felt like a water filled back cushion. Although if it moved even slightly, it would uncenter my weight and unhelpfully direct my trike toward the road’s margins.

Up until the moment of departure I had not decided what to do with my balky forearm crutches, which I needed for walking. With my legs fully extended in the trike’s footrests (and functionally useless), I was tempted to affix my sticks to them with tape or hook-and-loop strips, like an ungainly tomato stem on a tall wooden stake. But Neil wouldn’t have it. He came sporting a gear set-up like the one professional racer/adventurer Lachlan Morton used on his unsupported solo Tour de France expedition that year. He had extra room for everything.

The day could not have been more pleasant. It was a tidy 40 miles to our overnight stop near Rye, the scenic high point of New Hampshire’s modest 18-mile-long seacoast (the shortest of any state bordering the ocean). We cruised along with a nice tail breeze, passing bucolic horse farms in Ipswich and sun-worshiping Hampton Beach day-trippers where my low-riding set-up gained high praise and dozens of second looks. Whoops rained down from two-story Ocean Boulevard sundecks and the icy-drink revelers at Bernie’s Beach Bar. “Fuck yeah,” agreed a young woman looking up briefly from her phone. Several stuck out their phones to video me.

Ocean Boulevard, likely the most popular cycling road in southern New Hampshire, drifts along the Atlantic in North Hampton, inviting dreamy views seaward to the Isles of Shoals, a smattering of wind-blasted islands looking impossibly near despite being six miles out to the sea. Our overnight lodging was here, the home of an old college friend that overlooked a pebbly beach.

Spouses and friends converged on Ocean Boulevard after the ride, while riders who’d be joining us for the following day arrived. The trip had evolved into a sprawling reunion of half dozen of us who once shared a summer house after college. They were people who had isolated during Covid but were hard to find even before that.

I was one of them.

In the evening, a full moon rose, and a shower of cascading lights fell from a nearby fireworks show.

We had planned to beat the expected next day rains by waking at sunrise for an early start. But then everybody in the house woke at sunrise and we had breakfast instead.

In riding with friends to friends I had seemed to stumble upon the reason I was doing this. There were probably other reasons, too, with a part of me wondering if I could resurrect the feeling of touring again…how the hours stretched out across the endless daylight of a mid-summer day, how a bottom of the pack salvaged Snickers bar felt like a revelation, how ticking over pedals mile after mile could cause you to think of everything and nothing.

I wasn’t worried about keeping up with the others. I could maintain a decent enough 13 mph pace. It was something else. I was used to riding alone. When friends saw my low rider in person for the first time, I knew it was hard for them not to judge.

Fellow riders who saw me on Beverly area roads sometimes reported back to my friend Marc, the owner of my local bike shop, with suggestions for a taller flag, brighter taillights, yellower shells. And there was the time my former neighbor waved me down on the street, and grabbing his crotch area with two hands, exclaimed, “Dude, you have to have ones like this…”

My bike, odd looking as it was, flying a flapping lime green flag as it did, low, low, low as it went, wasn’t my first idea, wasn’t as I dreamt riding life would be at this point in my life. But it allowed me, when I rode alone, to feel independent. I felt normal and strong in a way being off the bike never would again.

The contrast with walking was stark. Six months earlier I fell at a rest stop on the Mass Pike, shattering my left hip. I’d never felt more infirm. Being part of a whimsical bike adventure in summer was the furthest thing from my mind.

I flashed back to when I was similarly surrounded on our first riding day—a semi-circle of guys, them standing, me looking up to them. We were taking a water break at a low bridge looking out to Plum Island, an 11-mile-long barrier island known for shedding houses into the sea. Neil searched through his endless Mary Poppins bags and fished out a yo-yo that he had apparently been perfecting in his recent retirement. “Walk the dog” was the opening salvo in an impressive array of higher-level tricks.

For several minutes we had nowhere to go. I lay happily transfixed by the recoiling yo-yo line, the lazy Parker River beneath me, like one of the kids in the overgrown sun-bathed outfield in the movie The Sandlot.

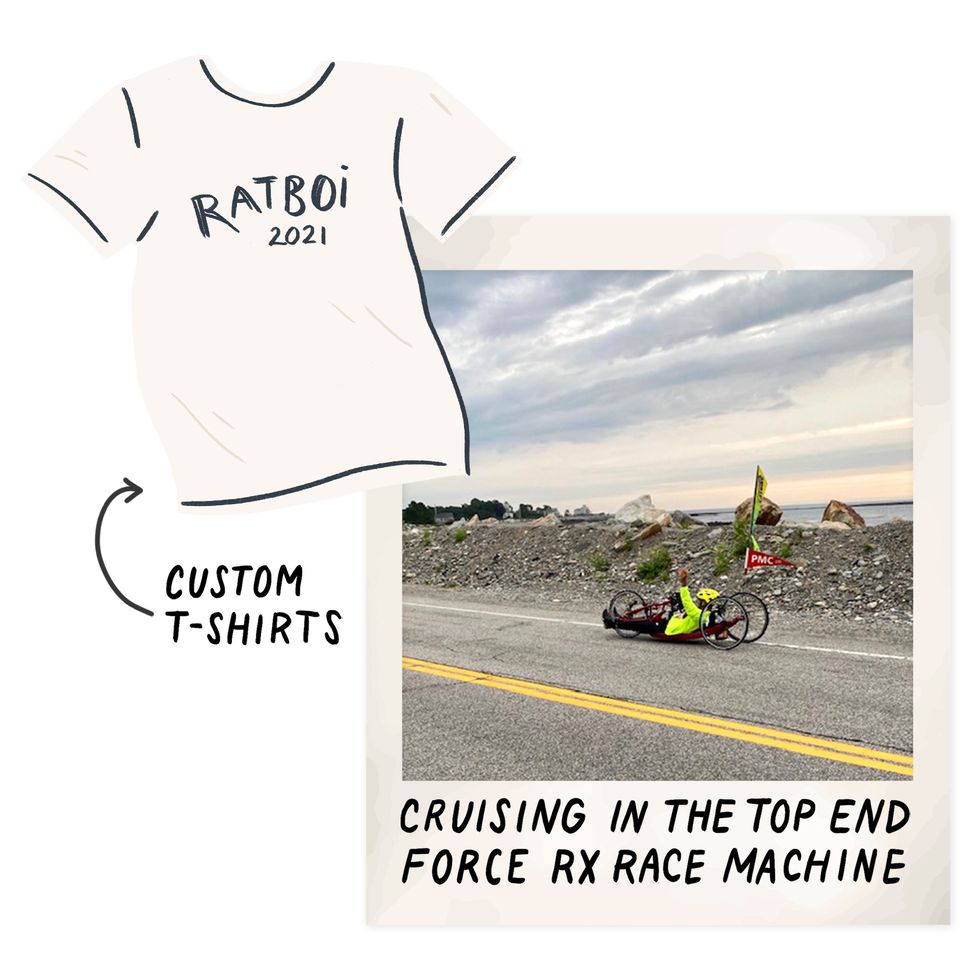

As predicted, it did rain the following day. All morning. My brother was wearing a heavy yellow sou’wester circa 1991. “I have an extra lightweight shell if you want it,” I offered beforehand, but he declined. He also had his fraying yellow panniers, harkening back to a Nova Scotia trip he’d done as a teen in the 1970s by using the same gear. When he rode his bike to Cape Breton Island, he became the first person I knew to cycle tour. Back then, when I chiefly occupied myself writing fan letters to the Dallas Cowboys “Bullet” Bob Hayes, I thought he was weird. But as tended to happen with anything my older brother did, it rubbed off.

Tom hadn’t just brought the sou’wester and panniers—he was also riding my old Scott bike, which I had given him when I couldn’t ride upright anymore. The retro vibe made him very happy. “I feel really good,” he announced about 20 miles in, like he was an adventurer in an REI ad and not a man sweltering inside five pounds of vulcanized rubber.

Brad, my old college roommate, was today’s guest rider. His most recent job was co-manager at Grain Surfboards, an acclaimed workshop making beautiful wooden boards. After leaving his full-time job Grain, he had let himself go a bit in pursuing, as he put it, “a life of the mind.” He was heavier and hairier with unruly muttonchops, but he had begun riding again in the last few years. Brad had once accompanied me in Colorado and Utah on the 142-mile Kokopelli’s Trail, in a ludicrous attempt to speed trial it in 48 hours by riding both night and day. Then—in the cliff-edge darkness of the desert—and now, as the rain swamped us for 40 miles from Kittery to Kennebunkport, he framed our experience with a simple question: “Is this fun?”

We made it on time to the memorial. The venue was the Abenakee Club —a century-old cottage-style clubhouse with a wraparound porch. On a point of land surrounded by ocean, we said goodbye to Andy, a husband, father, brother; a sailor, alpinist, skier, and fellow cancer cyclist. We had been diagnosed within weeks of one another, he with Stage 4 lung cancer. He had never smoked, his targeting as seemingly random as my own. He had been my model, and the stories from the podium in a big breezy tent only reinforced it. A sailing friend talked about plans they’d made to build their own boat, which they flirted with calling Row v Wade. His adult children remembered his sense of humor and his always answering the phone. Covid had interrupted our collective goodbye. No longer. The wind shifted as we exited the tent, fittingly blowing out the last rain clouds for blue skies and late afternoon sunshine.

When I had originally signed up for RAGBRAI, I called Jan to let her know I couldn’t make the memorial. I knew she would understand, and I knew Andy would’ve too (one of the attendees cycled 150 miles to get to Biddeford; I wasn’t Andy’s only nutty friend). All day as we rode to Biddeford Pool, the pull was discernible, and the closer we got, the more I understood our arrival was the figurative and literal center point of our trip. Andy, despite his sickness, seemed to grab every window of opportunity, famously flying out the door when the medicine temporarily cleared his lungs to ski, bike, play in his coffeehouse band, and romp with his first grandson.

As we rode the day’s final 10 miles to Old Orchard Beach, having left late and pedaling all out to beat the darkness, it occurred to me in the strongest way yet, we had grabbed a window. We were a trio of 60-year-olds heading north. Tom with two recently rebuilt knees, Neil a fellow cancer survivor with a trip-wire bad back. Me, six months out from a prone position on a pale white restroom floor. Andy would’ve liked the RAGBRAI idea just fine, but he would’ve loved this.

Day three was the longest day, some 60 miles from Old Orchard Beach, past Portland to West Bath. Our intended primary route was the Eastern Trail (ET), the main biking corridor in southern Maine. The longest off-road section intersected with our route at Saco, featuring shady woodland cinder stretches that feed into a two-mile long causeway across the spectacular Scarborough Marsh, the largest saltwater marsh in Maine. Snowy egrets and herons abounded, with islands of native grasses appearing like floating haystacks.

We stitched together paths into and out of Portland, taking Route 1 alternatives including the Eastern Promenade Trail near Old Port that leads to Back Cove. There we said goodbye to the ET and continued further along the East Coast Greenway before ditching it in Bath, where it begins to jog north to complete the final portion of the 3000-mile trail to the Canadian border in Calais, Maine.

In Falmouth, we met Steve, a roommate of Tom’s three decades earlier. He had planned to meet us at Town Landing Market, the iconic general store in Falmouth Foreside, but then he just appeared on the side of Route 88 a few miles earlier, carrying drinks, salty snacks, and whoopie pies. The spot he had chosen was the site of his wedding, the Episcopal Church of St. Mary, a handsome stone chapel on sweeping grounds.

Grant met us there too. He was another college friend of Tom’s who had rarely been seen of late as he dealt with a serious cancer condition. He was hesitant to talk about his ordeal, except to say he was starting to find a bit of footing. His immune-compromised system had to be guarded, there were more doctors’ visits coming, but he could still get his boat out, he said, making it up and down the steep hill to the launch ramp. “Be careful,” he said, eyeing me, as he simultaneously scanned the long downhill grade in front of us.

I was never much of a speed demon in my upright riding life, preferring instead steep climbs, including New Hampshire’s grueling Mount Washington hill climb one year. But now I craved speed, in part because I crept so slowly in the rest of my life, from the 13 stairs to our 2nd floor bedroom to Main Street crosswalks where I took all the allotted time to make it from one side to the other.

Neil and Tom, cautious at first, were happy to let me go on long downhills, happy to climb ahead on steep inclines. We established a nice rhythm. When to push, when to chill. Neil and Tom started to get used to me, when to help, how. They worried more than they let on, sometimes riding as personal guardians through busy intersections, or standing around while I attempted to get to my feet.

Now, though, a couple of days in, their watchfulness eased. When we stopped for coffee, nobody did anything. Neil left my poles on the ground for me and went to join Tom to order. I slid off my bike seat and found a bench, levering upward from kneeing to standing, using a modified push-up. They had seen it many times now, me finding tables, trees, and trash cans to repeat the process. They had stopped thinking about it. I stopped thinking about them thinking about it. We were just riding.

Neil was one of the first people to know I was sick. I told him at a cyclocross race in Gloucester. When I got out of the hospital, he brought me a stationary recumbent bike so I could begin to turn pedals again. Before cancer, and after, we ran a bike advocacy group with grand hopes to transform our little city into a mini-Copenhagen.

Neil fell in love with cycling when he lived in Maine in the ’90s, well before his move to Beverly when I met him. I knew he wanted to lead on these roads as we approached Westport Island. I put my Strava and Google Maps aside.

South of Freeport, maybe 50 miles along we came to a juncture with a popular route that tantalizingly dropped down to a ragged inlet carved by Harraseeket River. Likely more hills. “I know you want to go that way,” Neil said, a reference to my annoying lifelong habit for self-punishment. “No, no, I’m good,” I said.

Neil navigated us northward from Freeport to Brunswick along Pleasant Hill Road, in and out of the Bowdoin College greens to the 8-mile bike path that stretches along the Androscoggin River.

We arrived exhausted in West Bath, just prior to sundown at the seasonal cottage of another pair of Beverly friends who had left a welcome note and fresh cobbler. Their backyard was the New Meadows River, a tidal inlet flowing into northern Casco Bay. Tom ambled down the long dock and jumped in.

Neil sat at the top of the arrow straight gangway and seemed to be drinking it all in. He didn’t tally ride miles or elevation gained like most cyclists. He wasn’t overly concerned about fitness either. He rode for this, for seeing something he hadn’t seen before.

In the morning, with only a 25-mile ride to Westport Island and Neil’s promised oysters remaining, Tom announced he had to scrub. He had been up all night with a stomach bug. Neil’s wife Karen would pick him up and we would meet at Westport later in the day. Tom separated out the clothing of mine he had been carrying. It gave me pause. Tom has never not been there for me. Through teen breakups and periodic depressive episodes, he was the big brother with the gentle touch, calling or showing up when I didn’t want to talk or see anyone. Exactly seven years ago, on the eve of my radical cancer surgery, he and my wife Patty had emailed friends to ride that day in solidarity. It didn’t seem right that Tom wouldn’t finish. “It’s okay, I know I can bike 25 more miles,” he said. “But I also know there is a fair chance of me having to leave my underwear on Route 1 if I do.”

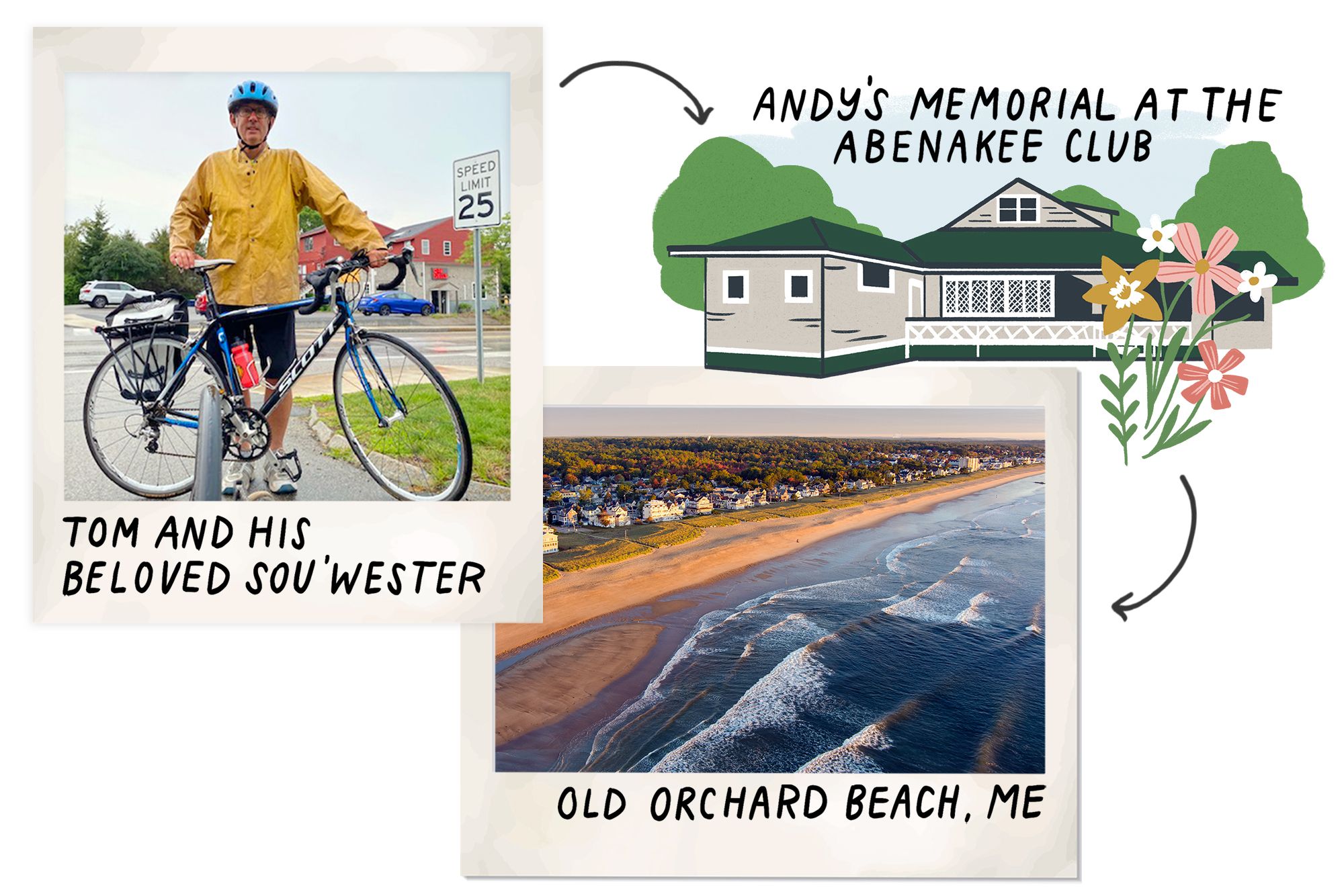

Neil and I had a civilized day, beginning with muffins at Bath’s Café Crème, and an easy ride across the Sagadahoc Bridge over the Kennebec River and onward to his home.

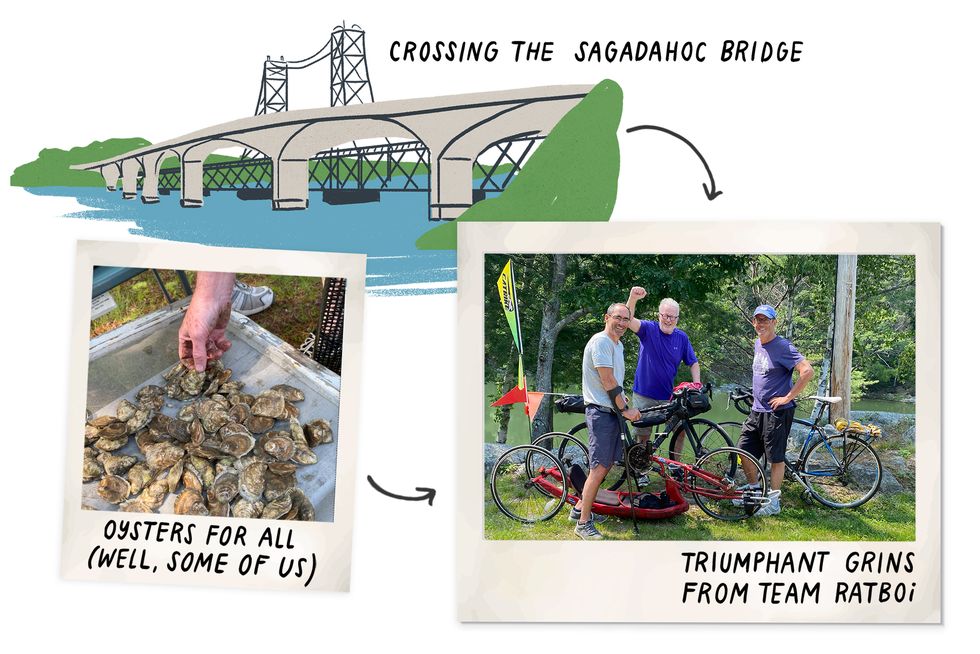

As promised, he swam out to his submerged oyster cages, fished one up, and cracked a half dozen. Tom excused himself from eating but rallied for the team photograph, taken on the little bluff above the tidal flats.

The picture of three men grinning next to their bikes reminded me of ones I had seen of our parents with their friends at a beach shack they all shared for a couple golden summers on the Gulf Coast. We were about the same age, an age where it’s impossible not to smile at the smiles.

I was 54 when I became disabled. I’m still young to it. I still feel the push-pull of wanting to be accepted and excused.

When I wrote my first draft of this story, a funny thing happened. I didn’t do a very good job explaining what it feels like to ride as an adaptive cyclist. It surprised me because for the last several years it’s all I’ve thought about, the difference between me and everyone I know who rides a bike.

But maybe, in the heady immediate aftermath of a first successful tour, my draft reflected a feeling I was left with. That I felt less different, less of the weird guy with a funky bike, and nothing more or less than a capable cyclist on a tour with friends in a beautiful part of the world.

Two weeks later I completed a 100-mile charity ride in seven and half hours, doing everything, as planned, by myself. I drove to the start, unloaded my rig, rode the loop south of Boston, and packed back up for the return home. I was pleased by an earned effort, and even felt the radiating warmth of the thousands-strong pack. But it also struck me that the day was a solo endeavor among cyclists I’d never met before. There was a bright finish line, but no oysters at the end.

Todd Balf is a longtime contributor to Bicycling and the author of Major (a biography of Major Taylor), along with several other books, including Complications, a memoir of his recent medical odyssey.