In honor of Black History Month, we highlight these incredible stories of Black cycling pioneers who helped to shape the sport while enduring structural inequalities that perpetuate racism and oppression.

Despite the odds, these riders set world records, helped to desegregate cycling, demonstrated the utility of a bicycle for military travel, and advocated for sisterhood and athleticism in the outdoors. Their accomplishments, almost unimaginable in the present day, demonstrate how far Black cyclists have come and how far we still have to go.

The Indomitable Legend, Succeeding Against All Odds

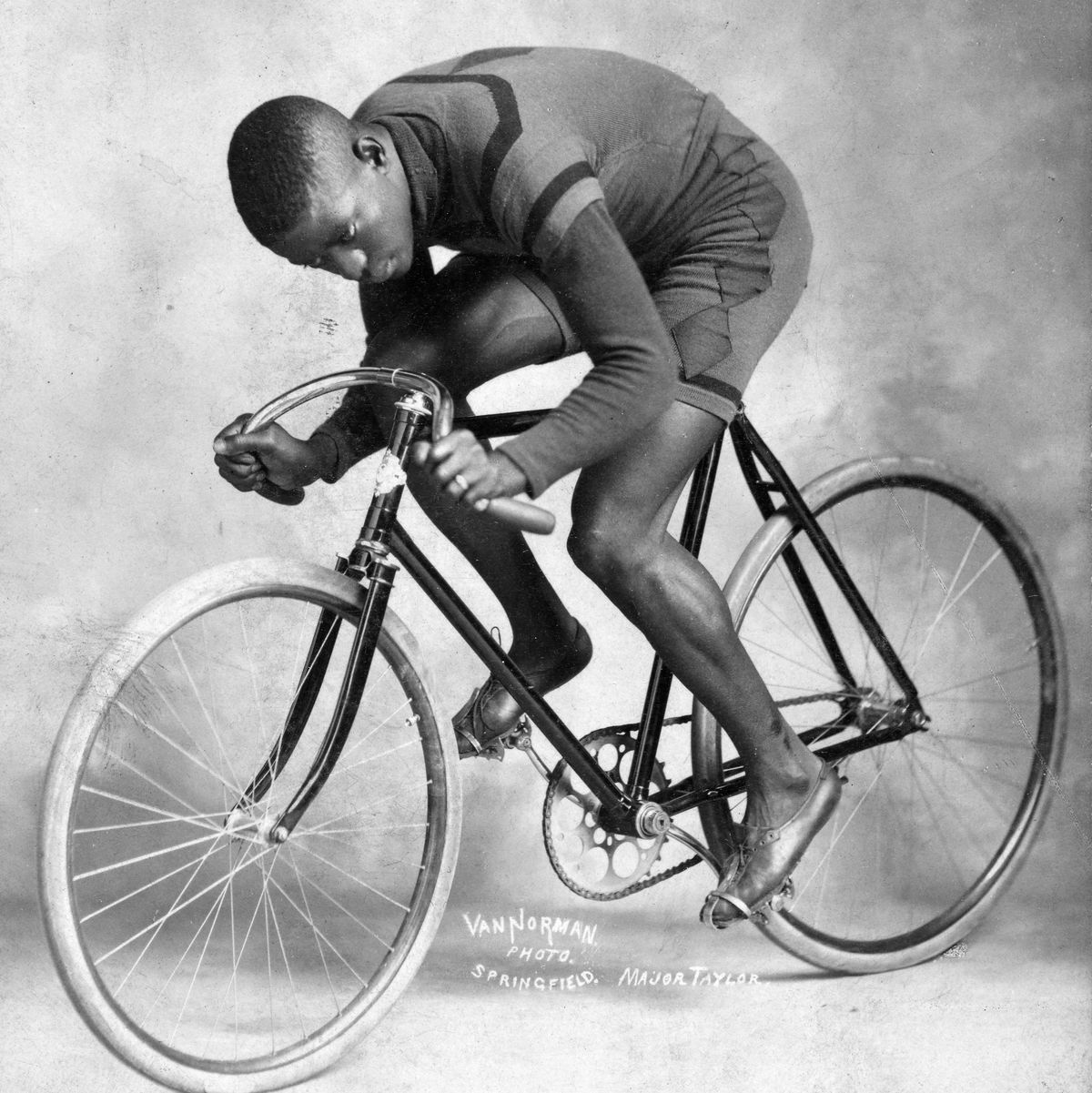

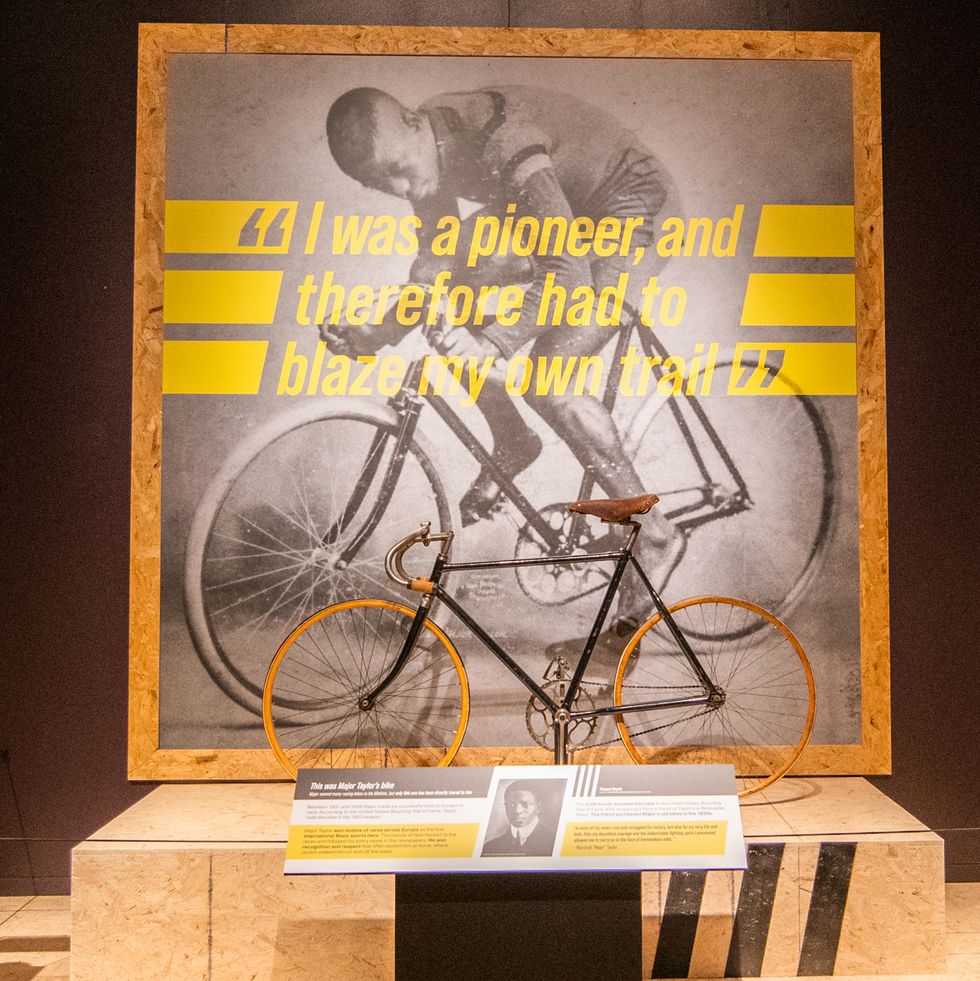

Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor, the first African American cycling legend, captivated the cycling world at the turn of the 20th century. Once referred to as the fastest man alive, Taylor dominated

More From Bicycling

Born to descendants of enslaved people in 1878 in Indianapolis, Indiana, Taylor was one of eight children. His father was a coachman for the wealthy Southard family. When his father worked for Mr. Southard, the Indianapolis, Peru, and Chicago Railroad superintendent, Taylor lived with the family, received a semiformal education with their son Dan, and got his first bicycle.

The Southards moved to Chicago when Taylor was about 12 years old, and he started working at the local bicycle shop: Hay and Willits. As a trick rider wearing a military-style uniform, many think that’s how Taylor got the moniker, “Major.” Not only was he skilled, Taylor also had speed. At 14 years old, he obliterated a field of top amateur cyclists in a 10-mile race, and by 1895 he won a 75-mile road race. Such incredible feats garnered unwanted attention and death threats.

Like other African American athletes of this time period, Taylor was often prohibited from competing because he was black. For some events, he was smuggled into the race by his sponsor. When he was allowed to toe the line, he was denied access to hotels and public spaces reserved for whites only.

Driven to succeed, despite continued racial harassment, discrimination, and assaults, Taylor dominated podiums stateside and overseas. In Europe, he took the top spot in 42 of 57 races, broke seven cycling world records, and won multiple world and national sprint championships from 1899 to 1902, earning about $35,000 annually.

At the end of his career, Taylor faced unfortunate circumstances. He lost most of his wealth to bad investments and the stock market crash of 1929. At age 53, Taylor died in a charity ward of the Cook County Hospital and was buried in an unmarked grave. Throughout his life, Taylor faced insurmountable odds, yet he prevailed and declared in his autobiography that “life is too short for a man to hold bitterness in his heart.”

Katherine “Kittie” Knox: The Graceful Trailblazing Cycling Pioneer

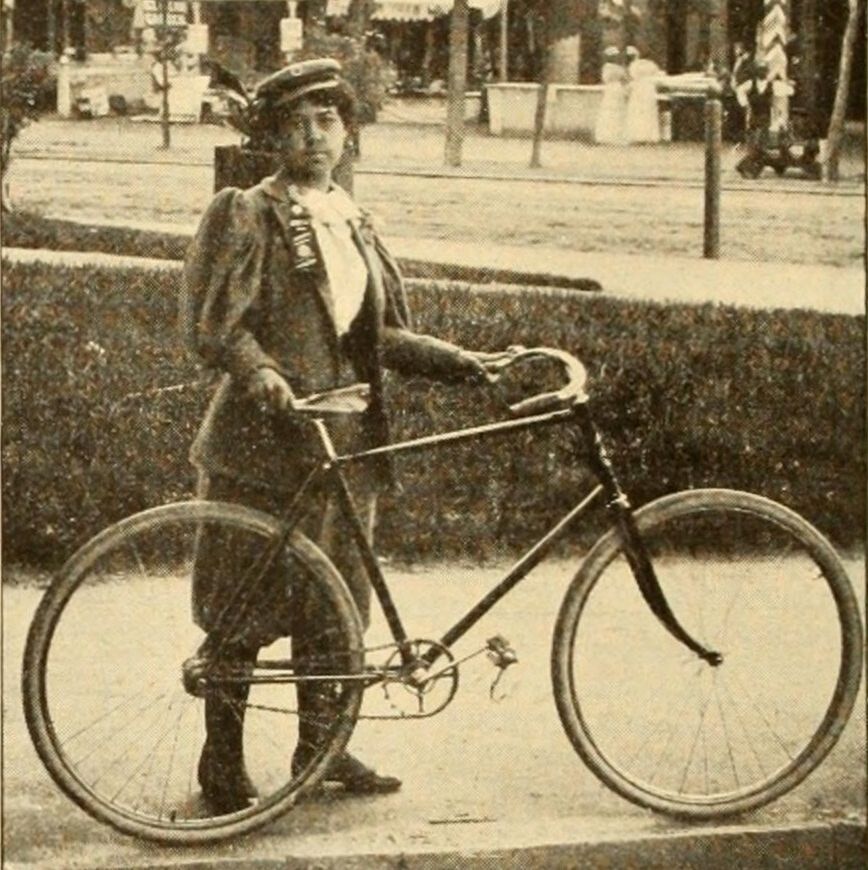

Katherine “Kittie” Knox, a bicycling pioneer and trailblazer, revolutionized cycling in the 19th century. A talented seamstress and cyclist, Knox’s skills were undeniable; yet misogyny and racial discrimination perpetuated by fellow cyclists made her journey even more challenging.

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1874, Knox was the second child of Katherine Towle, a white mill girl, and John Knox, a Black tailor. Her father died when she was 7 years old, and the family moved to a predominantly African American neighborhood in Boston’s West End.

The young seamstress soon picked up cycling, and before long she owned her own bicycle. Knox rode a male-specific bike instead of the traditional step-thru frame marketed for women. She opted for knickerbocker suits with baggy pants instead of dresses, to the consternation of many. When racing, she lined up with men, competing in races as long as 100 miles and consistently finishing in the top 20 percent.

In 1893, Knox joined the Riverside Cycling Club, Boston’s only Black cycling club, and the majority white, male League of American Wheelmen. The following year, the League voted to deny membership to nonwhite cyclists. With a “color bar” in the League’s by-laws, many white male members protested Knox’s membership.

In July 1895, Knox traveled to Asbury Park, New Jersey, for the League’s annual meeting. As a card-carrying member, she was entitled to tickets that granted her various privileges. However, upon arriving at the League’s headquarters, she was denied entry.

“When Ms. Knox, whose appearance and dress had been objects of admiration all day, walked into the committee room at the local clubhouse and presented her league card for a credential badge, the gentleman refused to recognize her card,” the San Francisco Call newspaper stated. It was later determined that the “color bar” could not be applied retroactively. Knox’s membership stood despite racial opposition.

Knox’s courage helped to highlight racial injustices that women and Black people faced. At 26, her life was cut short by kidney disease, and she was buried in an unmarked grave. A monument was later erected in her honor at Mount Auburn Cemetery, located between Cambridge and Watertown.

More than 120 years after her death, Black cyclists still face similar prejudices in the cycling industry.

The 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps: Buffalo Soldiers From Montana to Missouri

In the late 19th century, the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps, stationed in Fort Missoula, Montana, enlisted 20 Black soldiers to show the feasibility of using bicycles in military operations. These Black infantrymen, sometimes called the Buffalo Soldiers or Iron Riders, embarked on “the Great Experiment.” Cycling 1,900 miles from Montana to Missouri, these pioneers, perpetually perceived as inferior in courage and ability, endured hostility and racism; yet they persevered and accomplished the mission.

U.S. Army 2nd Lt. James Moss, commanding officer of the 25th Infantry and an avid cyclist, wanted to show Army leadership that bicycles were more practical than horses for transporting soldiers. On May 12, 1896, the Army approved Moss’s bicycle experiment, but it allocated no funding. To bring his dream to fruition, Moss contacted the A.G. Spalding Company to get bicycles for his soldiers.

With the steel frame Spalding bicycles weighing 60 pounds fully loaded, the experiment was limited to riders 24 to 39 years old, weighing 140 pounds and no taller than 5 feet 8 inches. Each rider also carried a 10-pound rifle and a belt with 50 rounds of ammunition.

On June 14, 1897, the Buffalo Soldiers embarked on their five-state journey. Before leaving Montana, they endured heavy rains that turned the mud to a gumbo-like consistency. Along the Continental Divide, weather conditions shifted to sleet and snow, reducing visibility to about 20 feet; between Montana and Wyoming, the soldiers were forced to cross the Little Bighorn River while shouldering their bicycles. Deep sand in Nebraska, a “monotonous series of hills” in South Dakota, oppressive heat, and illness from drinking alkaline water made an arduous trip almost unsustainable. When the soldiers stopped to rest, townspeople along the route were almost as challenging as the weather. The Kansas City Journal reported that “when away from the railroad, the people were inhospitable” to the soldiers.

Averaging 56 miles a day, the Buffalo Soldiers approached St. Louis, Missouri, on July 24, 1897. Like much of the trip, the this part of the journey was fraught with heavy rains, heat, and mud. After 41 days, 1,000 cyclists greeted the soldiers in Forest Park.

“An Army bicycle corps can travel twice as fast as cavalry or infantry under any conditions, and at one third the cost and effort,” Moss told the United States Army and Navy Journal at the time.

Over 125 years after the Buffalo Soldiers’ historic feat, their story remains relatively unknown. Despite harsh environmental and social conditions, they endured. Last year, the Missouri State Parks celebrated their contributions with reenactments and exhibits along the historic route.

Riding 250 Miles for “Love of the Great Out-of-Doors”

Almost 95 years ago, five Black women mounted their bicycles and set out to pedal 250 miles from New York City to Washington, D.C. Their historic journey, an uncommon feat in 1928, captured the attention of news outlets and redefined the narrative of bike touring.

It was 6 a.m. on Good Friday, April 6, 1928, when Marylou Jackson, Velva Jackson, Ethyl Miller, Leolya Nelson, and Constance White departed Manhattan and rode 110 miles to Philadelphia. The women spent the night at a Young Women’s Christian Association branch. On day two, the group rode approximately 40 miles to Wilmington, and on Easter Sunday they rode another 100 miles and arrived in D.C. around 9 p.m.

Upon arriving, the avid cyclists visited the National Mall and Howard University. Stylishly dressed in leather jackets, caps, bloomers, and eye-catching socks, the group posed in front of the Washington Tribune newspaper building for their historic photograph, taken by the prominent photographer Addison Scurlock of the famous Scurlock Studio.

Miller and her compatriots rested at the Phyllis Wheatley YWCA. They loaded their bikes on a train the next morning and traveled back to Manhattan.

At a time when people of color were fleeing the South and cycling, then as now, was mostly the domain of white men, the five friends—Velva Jackson, a nurse; Nelson, a director of physical education; Miller, a teacher; and Marylou Jackson and White, both students—rode to publicize and elevate women cyclists. Asked why they embarked on the journey, the women said it was for their “love of the great out-of-doors.”

Later, the women challenged other female cyclists who were 21 and older to complete the same route in less time. Though the exact route of the 1928 ride is unknown, cyclists continue to memorialize these five friends by riding between these metropolitan cities. Most notably, Major Knox Adventures, a women-led movement that “promotes sisterhood, athleticism, and supports and amplifies the stories of Black women experiencing joy in the outdoors,” hosts the 1928 Legacy Tour. Like Jackson and her friends, the Legacy Tour starts in Harlem, covers 250 miles, and riders finish in D.C. on the third day.

These stories originally appeared in the weekly Bicycling members-only newsletter. To get more exclusive content and expert advice from coaches and experts, become an All Access member today!

Taneika is a Jamaica native, a runner and a gravel cyclist who resides in Virginia. Passionate about cycling, she aims to get more people, of all abilities, to ride the less beaten path.