What makes for a great bike city in America? Is it the miles of protected bike lanes? The number of coffee shops? An abundance of stunning places to ride?

Yes to all of that, but as we sifted through thousands of data points and chatted with bike advocates and transportation officials around the country, we determined that the best cities are the ones that don’t cater to one specific type of rider—be it the daily commuter or competitive roadie. The ones that top our list have built systems and a riding culture that benefits everyone—from the kid who rides to school to the retiree who takes a weekend trip to the grocery store.

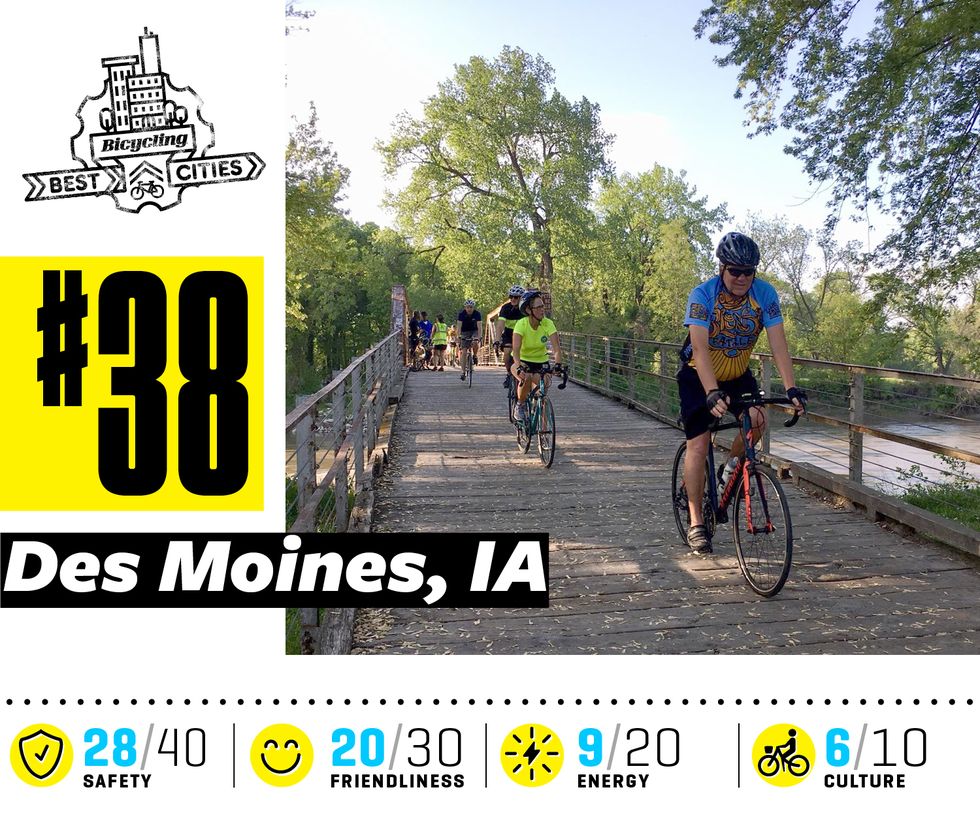

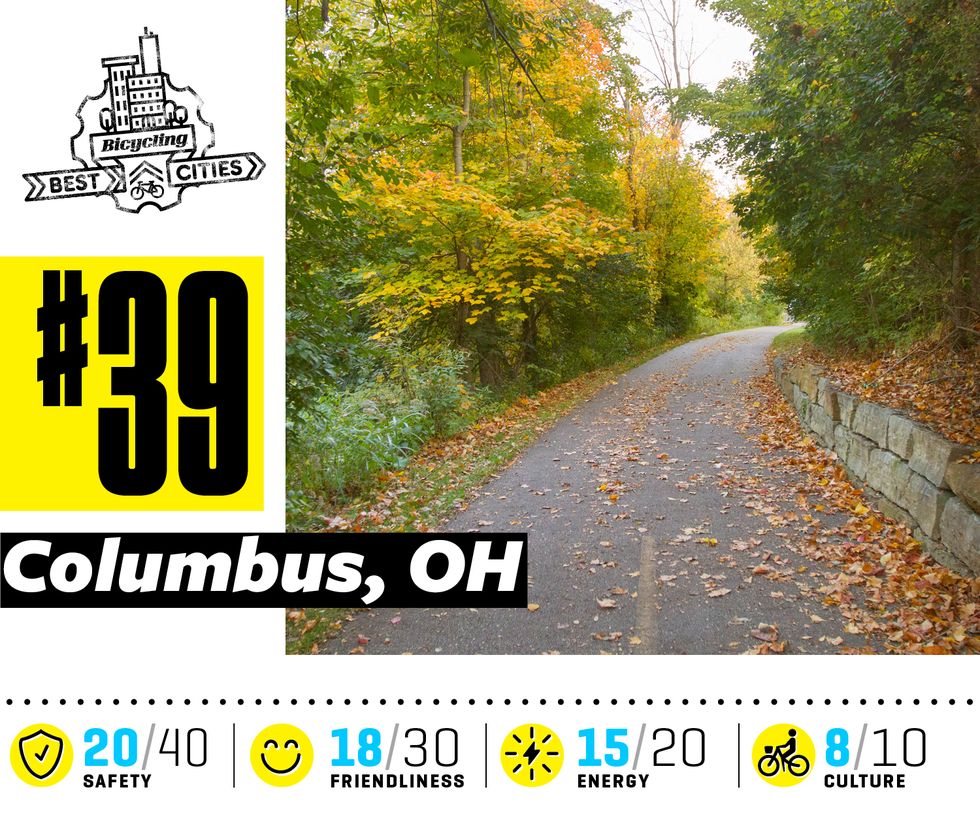

Our ranking system is out of 100 points divided into four categories, each weighted based on their importance. Safety tops the list and is ranked out of 40 points. Eight to 80 friendliness (how accessible the city is to riders of all ages) came next out of 30 points. Then energy—a measure of the political climate in regards to bikes—out of 20 points. Finally, culture—the shops, routes, and attributes that make each city a great place to ride—was ranked out of 10 points. For a more detailed look on how we ranked each city, go here.

One takeaway we can’t stop thinking about is that there is no perfect American city for cycling. Our networks are still fragmented. Some cities have nothing besides paint-on-pavement lanes. Many socioeconomically disadvantaged communities lack any bike infrastructure at all. And we don’t have any one organization that collects comprehensive data on cycling injuries. America has a lot of work to do. But a few cities are leading the way, and seeing the work they're putting in makes us hopeful that other areas will soon follow suit.

Check out how your city ranks below.

2016 Ranking: 5

Very few bike lanes in the country are being built with the attention to detail that engineers in Seattle are using. Protected lanes sport concrete buffers—the gold standard for protected lanes—and at intersections, riders can lean on lean rails as they wait for their cycling-specific signal to change. “The city has done some really impressive things,” says Tom Fucoloro, editor of the Seattle Bike Blog. “The Second Avenue protected bike lane takes you all the way from the Space Needle to Pioneer Square on a nice, protected bike lane that’s really fun to ride.” A few miles away, the West Lake Cycle Track was even chosen as the best bike facility in North America by People For Bikes.

Seattle is going through a major growth spurt, with 60,000 new jobs added downtown between 2010 and 2017. That’s forcing a lot of conversations about how to move people in and out of town each day. Bikes have been at the forefront of those conversations, with elected leaders actually taking DOT staffers to task for not building bike lanes fast enough. Oh, what sweet utopia is this?

Right now, things are going the way they should in every city: There are currently 60 miles of low-stress neighborhood greenways in the works, and connecting existing protected bikeways is a major priority, says Dongho Chang, a traffic engineer for the city. The Vision Zero initiative has also been taken seriously. “We timed all 300 traffic signals for 23 miles per hour,” says Chang. That’s significantly slowed traffic, which is a major tenet of reducing bike and pedestrian deaths. The city has also narrowed lanes and inserted speed tables and traffic islands—all of which calm vehicular traffic. Fucoloro even says that the will to reduce speeds was surprisingly universal.

One of Seattle’s true bright spots is its transit system. During the period when Seattle added 60,000 jobs, it somehow also managed to reduce single occupancy car trips by 9 percent. This shift was thanks in large part to a well-engineered—and therefore well-used—public transit system. So what does that have to do with biking? First and last mile bike commuting, where you ride to or from the bus stop, helps cut down on car traffic around transit stops. It can also help cities develop more infrastructure for bikes in high-transportation areas. For many riders, riding to and from a stop is an end unto itself. But it’s also how many bike commuters get their start. First, you’re just riding a mile. Soon, you’re going all the way to work on two wheels.

One final success story in Seattle is its bike share system—or lack thereof. Seattle’s bike share system, named Pronto, shut down in 2017. “It felt like a real loss,” says Fucoloro. But he adds that really, it turned out to be kind of a blessing. When start-up bike share companies were looking for a market to enter, Seattle was just about the only large city that didn’t have a system already up and running. From day one, there were bikes everywhere–something the first system had failed to do. In its first six months, 1 million rides were taken on Limebikes in Seattle. “It turned this failure into a real success.”

2016 Ranking: 2

In 2010, the city of San Francisco didn’t have a single protected bike lane. “Five to six years ago, getting paint on the ground felt like a win,” says Brian Wiedenmeier, the executive director of the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition. “Now there are 10 protected bike lanes across the city,” which equate to almost 20 miles of protected riding bliss. Even better, between now and 2021, the city is investing $112 million in bike-related improvements.

The city also drastically reduced its traffic fatalities in 2017, from 30 in 2016 (including motorists and pedestrians), to 20 in 2017. “We’re really taking a data-driven approach to this,” says Wiedenmeier, adding that the city also has been extremely aggressive when setting goals for both maximizing safety and minimizing single-user car trips.

Amazingly, it’s actually reaching many of them. For example, one of those goals was to make 50 percent of all trips in the city via sustainable methods, like biking, walking and mass transit. The city hit and surpassed that mark in 2012, and has since upped it to 80 percent of trips being via sustainable methods by 2030.

No city is without its problems, though. The Bay Area’s current headache is ride-share programs, like Uber and Lyft. A few years ago, when rideshare first entered the marketplace, many thought that it would reduce car ownership and cut back on overall car trips. But that hasn’t happened. In San Francisco, those cars are so easy to find that people are using them instead of walking, biking, or taking the subway across town. “There are 20,000 additional vehicles in the city now that are Ubers or Lyfts. On many streets the bike lanes have been taken over by literally hundreds of loading and unloading vehicles that are illegally parked,” says Widenmeier. Ben Jose, the communications manager for San Francisco’s Sustainable Streets Division, agrees that rideshare is a nightmare for cyclists, and says finding solutions is a top priority. “We’re both trying to find better ways to use curb parking and ramping up enforcement,” he says, adding that the city has added a dedicated phone line where people can report cars illegally parked in the bike lane at any time.

Also, the city is trying to work as quickly as possible while still building high-quality infrastructure. This has been dubbed the “quick build” method, and it basically means that the city uses paint plus plastic or moveable concrete barriers to quickly get a protected bike lane onto a street, then allows the community to give feedback on ways to improve it. Because it isn’t expensive to do, there’s not much harm if a major design flaw is discovered, and it doesn’t have to go through as many channels of bureaucracy as something deemed “permanent.”

2016 Ranking: 12

Traditionally, these top spots have been saved for large cities, as a way of giving a nod to just how difficult it is to do good bike infrastructure in a giant metropolis. But Fort Collins is doing so much so right, that pushing the city down the list felt like a disservice.

What makes Fort Collins so great is that the city has focused on building pathways that move cyclists through town quickly and efficiently. “There’s little traffic in Fort Collins, but even without traffic it’s often faster to bike than to drive because of the multi-use paths,” says Will Hickey, who works with Bike Fort Collins. In many cities, pathways are simply old railroad beds that take you out of town, but in Fort Collins they are purpose-built, with under- or overpasses at nearly every main street crossing, so you rarely have to interface with cars at all. In fact there are currently 45 of these “grade crossings” (which means under- or overpasses) throughout the city.

You can tell that Fort Collins has built a successful low-stress network because its proportion of bike commuters—and that of female bike commuters—is almost double that of the top two cities. And even without a dedicated Vision Zero plan in place, the city has a very low cyclist fatality rate.

Like Seattle and San Francisco, Fort Collins is also in a period of rapid growth, and that’s complicating things. Hickey says that generally Fort Collins residents want more bike infrastructure, but things can get heated at city council meetings. As outward sprawl happens, more residents may want more car-focused projects. And both Hickey and Tessa Greegor, the Fort Collins Bikes Manager for the City of Fort Collins, say that equity is an issue, with some neighborhoods lacking access to the bike networks.

Still, it’s a great place to ride—both to the grocery store and to the local mountain bike trails, many of which you can get to via multi-use pathways. And with more bike friendly businesses than any other city in the U.S., your co-workers won’t give you side-eye when you roll up to a meeting with helmet hair.

2016 Ranking: 6

Thanks to a 19th century city planner named Horace W.S. Cleveland who believed cities should have green spaces, Minneapolis has always been full of outdoor recreational opportunities. That translates to miles and miles of off-street pathways going through and between these green spaces. The result is an amazing, low-stress web around the city. “I challenge anyone in just about any city to put together as nice of a 20-30-mile route as you can put together in Minneapolis,” says Matthew Dyrdahl, coordinator of walking and biking for the City of Minneapolis.

Minneapolis won this competition back in 2010, and it’s always near the top. But it’s been out of the top three spots in recent years because it’s playing catch-up when it comes to on-street infrastructure. That matters: If you can’t actually use your bike as transportation without battling traffic, that’s a problem. “Our bike paths have been here for a long time, and in the 90s and early 2000s we put in on-street bike lanes which are great for people who are confident,” says Dyrdahl. But the next step is expanding that network so it works for everyone, especially more timid riders.

Things are headed the right way. In 2016 the city adopted a complete streets policy, meaning all new design must prioritize walkers, cyclists, buses, and cars—in that order. And the city is currently in the midst of completing $15 million dollars worth of resurfacing and reconstruction projects, including $1 million just for protected bike lanes. “The city is also being proactive on improving the quality of the protection,” says Ethan Fawley, the executive director of advocacy organization Our Streets Minneapolis, adding that concrete curbs and planters are slowly replacing plastic bollards and posts.

Once Minneapolis improves its on-street lanes, the city will be downright amazing for biking. Sure, it gets cold in the winter, but the city has made a huge commitment to plowing bike lanes and pathways. “We have a 24-hour service goal,” says Dyrdahl, meaning all bikeways should be cleared within 24 hours of a snow, adding, “We don’t want to be a city that’s good for biking and walking from Memorial to Labor Day.” The culture here too is pretty unbeatable. Over 100,000 residents show up for the city’s regular open streets events, and on a sunny weekend it feels like the entire city is out riding.

2016 Ranking: 3

It’s always near the top, but there are a few reasons that this year, Portland isn’t at the head of the class. For one, we’re concerned that Portland residents are so good at getting around by bike that they’ve forgotten what it’s like for newbies. “We’re not doing the work to get new people on bikes,” says Jonathan Maus, of Bike Portland. In fact, he says that at council meetings he’s actually heard experienced riders arguing against the addition of protected bike lanes. “They’ve been cycling on streets for a long time and they figure that because they’re okay with it, everyone should be okay with it.” In fact, since we last put out this guide two years ago, Portland has only built 5.2 miles of protected lanes. Seattle and San Francisco built 15 and 18 miles respectively in in that same period.

More protected lanes are coming, though, says Hannah Schafer, a communications specialist with the Portland Bureau of Transportation. Between now and 2020, the goal is to build 24.4 miles of protected bike lanes throughout the city, focusing especially on parts of the network that have previously been neglected, says Schafer.

One of the big projects the department has planned will happen in Gateway, a neighborhood that’s traditionally been underserved by bike infrastructure. Equity, Maus says, is one issue that Portland is finally getting right. The bike share has low-cost memberships for low-income residents, and it’s one of few cities with an adaptive bike share that serves people with disabilities.

In May, Portland announced that it planned to make protected bike lanes a feature on 450 new roadways, making them more or less the standard. While that should be an awesome, exciting announcement, Maus and others in the advocacy space will celebrate once they see construction beginning. “In terms of spirit, Portland is an amazing place. But we’ve been resting on our laurels. We have to build protected lanes, and there’s been a lot of conversation about it but they haven’t done anything,” he says. “People here love bikes. If we actually built adequate bike infrastructure, we would leap over Copenhagen.”

2016 Ranking: 1

In 2016, Chicago was our winner, coasting to the top on its embrace of bike share and its beginnings of a protected network. It’s continuing to grow its low-stress network, but “unfortunately, there’s been a little bit of a drop off, particularly with protected bike lanes in terms of new miles going in,” says Jim Merrell, the Advocacy Director for Chicago’s Active Transportation Alliance. For example, between 2016 and 2018, the city built just 3.75 miles of protected bike lanes. In a 227-square mile city, that’s a small drop in a very big bucket.

To be fair, the city has put in 21 miles of buffered bike lanes and upgraded 2.5 miles of existing protected bike lanes with concrete curb protection, bringing the total amount of protected, buffered, and off-path roadways up to 176 miles. And it’s also working to upgrade the protection on the lanes that already exist, “So we’re moving from plastic posts to concrete curbs wherever possible,” says David Smith, a Senior Transportation Planner for the City of Chicago.

One thing that Chicago is acing is project funding. In 2018, bike-infrastructure related spending was an amazing $53.5 million. That money is coming from a mix of local and federal funds, says Smith, adding that the Divvy Bike Share Program’s revenues are also helping out. And, private funds have helped get things finished, too. One example of that is a $12 million gift that allowed the city to fully separate bikes and pedestrians on the Lakefront Trail. “It’s the busiest trail in the country,” says Smith. All 18 miles are currently undergoing a major upgrade as the city constructs a separate bike path to keep both pedestrians and cyclists safer.

Chicago is an enormous city and it’s impressive how well planners have managed to make bike infrastructure almost ubiquitous, especially downtown. Expanding outward is next. In 2017, the city purposely focused on adding new Divvy stations to underserved neighborhoods, especially in Chicago’s South and West sides. By the end of 2018, the city will have 600 operational stations. By 2020, the city hopes to have every single resident of Chicago within half a mile of an accessible bike route.

Finally, we docked Chicago a few points because its modeshare is still relatively low, especially among women. According to the U.S. Census, just one percent of Chicago’s women are getting to work by bike. That’s significantly lower than all the cities that came before it on this list, and a number we’d love to see grow in the future.

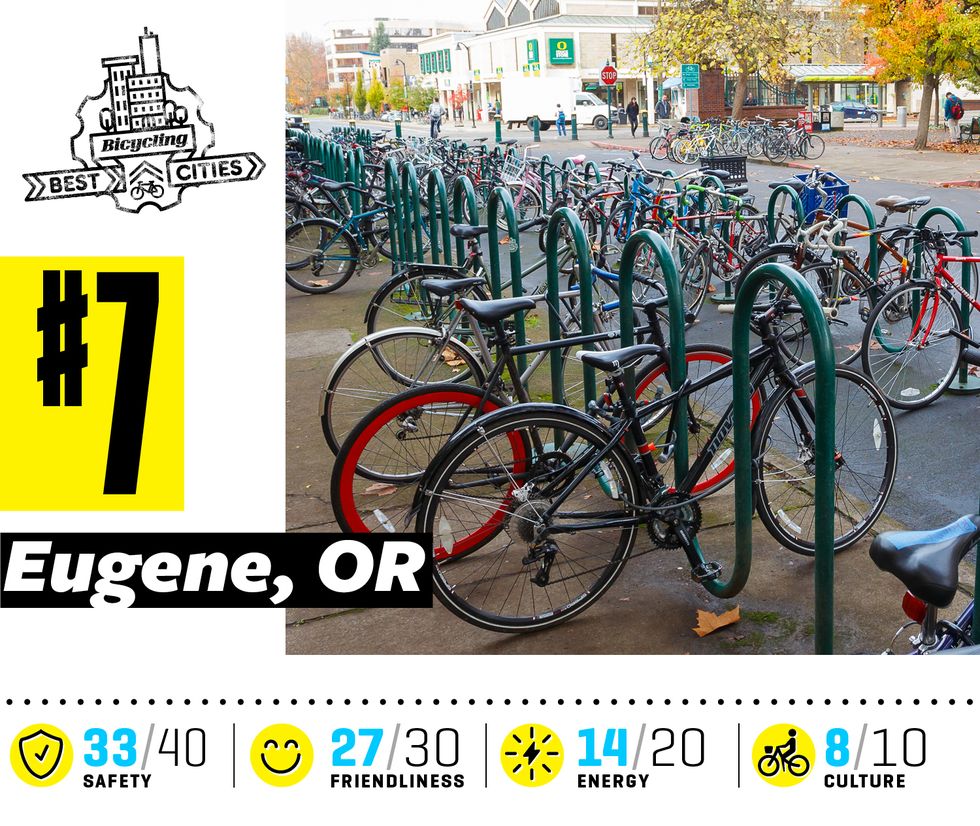

2016 Ranking: 18

Hippie Eugene has always been bike friendly—especially with all those college kids zipping around. Reed Dunbar, the bicycle and pedestrian planner for the city, says that the current focus in Eugene is on increasing connectivity. “We’ve built three bike bridges this year,” he says, adding that there are plans for three more. Eugene is also experimenting with bike-specific signaling at intersections, to keep riders safe as they move across lanes.

Eugene is starting to add more protected and buffered bike lanes too, including a two-way protected bikeway that will connect the University of Oregon to Eugene’s downtown. “We’re also adding buffers to existing bike lanes,” says Dunbar, adding that the city is specifically focusing on adding buffers to the door-zone bike lanes installed in previous decades.

While most cities have some sort of safe routes to school program, Eugene is taking the recruitment of kid cyclists very seriously. “We have three full-time safe routes school coordinators,” he says, adding that there are five roving fleets of bikes that are passed from school to school so every fifth- and sixth-grade student in the area learns how to ride.

2016 Ranking: 16

Madison is shaped like a bowtie, with downtown occupying the narrow middle part. “That makes getting in and out of town in a car a real challenge,” says Robbie Webber, a member of Madison Bike’s Board of Directors. However, it makes biking a super-efficient way to get around, which has probably helped grow Madison’s large bike commuting modeshare.

Plus, the city has long built for bikes—especially downtown. Madison has a nice web of existing off-street pathways. However, on-street infrastructure is still mostly limited to painted bike lanes. So far, Madison has only put in a single mile of protected bike lane, though Yang Tao, the assistance city traffic engineer says more protected lanes are coming.

One cool project the city is undertaking is a massive wayfinding mission. “Signage along routes will show distances and times to major destinations,” says Tao. Right now, the effort is focusing on signage and maps, but eventually may include an app.

While Webber says Madison truly deserves its “platinum” rating from the League of American Bicyclists, there are things she’d still like to see improved—like more bike connectivity outside the city center. “There’s this band that was built from the 1970s to the 2000s that’s really not built for walking or biking,” she says, adding that it’s time to address making places farther out of the city just as bikeable as downtown. “We’ve done a lot of the lower hanging fruit things, now it’s time to go for the harder projects.”

2016 Ranking: 4

It only took 40 years of lobbying, but cyclists finally have a car-free Central Park. “It was never even supposed to be a thoroughfare, it was supposed to be a respite and refuge from the city,” says Paul Steely White, the executive director for Transportation Alternatives, a local advocacy group. What took so long? Steely White says there was some opposition from motorists who feared traffic would worsen on nearby streets, but “for the most part it was political cowardice that kept it from getting done.”

While Central Park opens up six blissfully car-free miles, it’s more of a recreational win than a victory for the transportation network. Luckily, New York has been working on that too. “Our protected bike lane mileage has gone through the roof,” says Ted Wright, director of the Bicycle and Greenway Program for the City of New York. “In 2014 we were building five miles of protected bike lanes a year. In 2017 we built 24.9 miles.” In fact, the city now has 460 protected miles spread across the five boroughs. The goal for the next few years, adds Wright, is getting more connectivity to the bridges that connect the city.

New York is also piloting a few intersection projects to try and keep bikes safer. “These tougher intersections are where people get hurt,” says Wright. Right now, the city has 50 intersections that are allowing bike to go first, using the pedestrian signals, while cars wait. This gives bikes a few extra seconds to get into the intersection, thus being clearly visible to drivers.

All these improvements have helped the city grow its ridership. According to data from the New York Department of Transportation, 49 percent of New Yorkers now say they ride a bike at least a few times a month. The improvements have increased New York’s overall safety too. Data collected from the state shows a 74 percent decrease in crash risk for cyclists between 2000 and 2016.

Still, New York isn’t yet a cyclist’s utopia. In 2017, 23 cyclists were killed in traffic accidents, up five deaths from 2016. That’s something we take seriously, and one reason why the city, despite its many bike lanes, wasn’t closer to the top of this list.

Correction: A previous version of this story included fatality rates from 2014. The article has been updated with more recent statistics.

2016 Ranking: 8

“Cambridge depends on bicycles for its existence,” says Nathan Fillmore, the executive director of Cambridge Bike Safety, the local advocacy group. As a city, Cambridge is cramped. It’s just 7.1 square miles with 105,000 residents—plus tons of tech companies and Harvard University—crammed into it. “Our infrastructure is at 200 percent capacity,” says Fillmore. Which means biking is an appealing option.

The city boasts one of the highest modeshares in the country, with seven percent of residents commuting via bike. But Fillmore says that there’s still a lot of work to be done to make Cambridge truly bike friendly. “The longest protected bike lane in the Boston metro area is still only eight-tenths of a mile long,” he says, “and there really are no bike paths here.”

Cara Seiderman, the transportation program manager, says that the city is working faster than ever to get safer bike lanes online. “For the longest time we put in bike facilities when road work was going to be done,” she says. But with the city’s adoption of Vision Zero, that premise has shifted. “We had a couple of fatalities in one year and we realized that we couldn’t wait; that we had to build this stuff faster.”

The result is “quick build” projects, which can be done in weeks, not years. These projects move bike lanes out of door zones and protect them with plastic stanchions, then denote them with green paint and signs. Cambridge has also successfully navigated several road diets, which lowered speed limits and improved safety in areas that have previously been problematic.

Perhaps the best thing about Cambridge’s bike scene though, is its diversity. “The number of spandex clad bikers is really small, it’s more of a European city feel,” says Seiderman. “There’s a good diversity of ages and we do a lot of out-reach to seniors and non-English speaking communities,” she adds. “The random cross section of the population that’s out biking—just out doing their own thing on a bike—is really cool.”

2016 Ranking: 9

Our nation’s capital has done an excellent job investing in both trail systems and on-street infrastructure, so cyclists can zip in from the suburbs on pathways, but still feel safe as they connect from pathways to office.

One of the city’s recent big projects is the Anacostia River Trail, a four-mile section of trail that connects to 26 more miles of trail in Maryland. Traditionally, Anacostia has been an underserved community, so the trail was one step towards infrastructure equity, says Jim Sebastian, who works for the District’s Department of Transportation.

D.C. is also prioritizing programs that incentivize cycling in the city. The GoDCGo program works with employers make their offices bike friendly. And the 2014 DC Commuter Benefit Ordinance stipulates that all D.C. employers with 20 or more employees must offer transit benefits—like free bus passes or a bikeshare membership.

Finally, D.C. continues to be a leader on the safe routes to school program. Every single second grader in the city learns to ride a bike, and many of the schools have bike to school days where large numbers of students actually make their way to school by bike—something other cities are truly struggling to achieve.

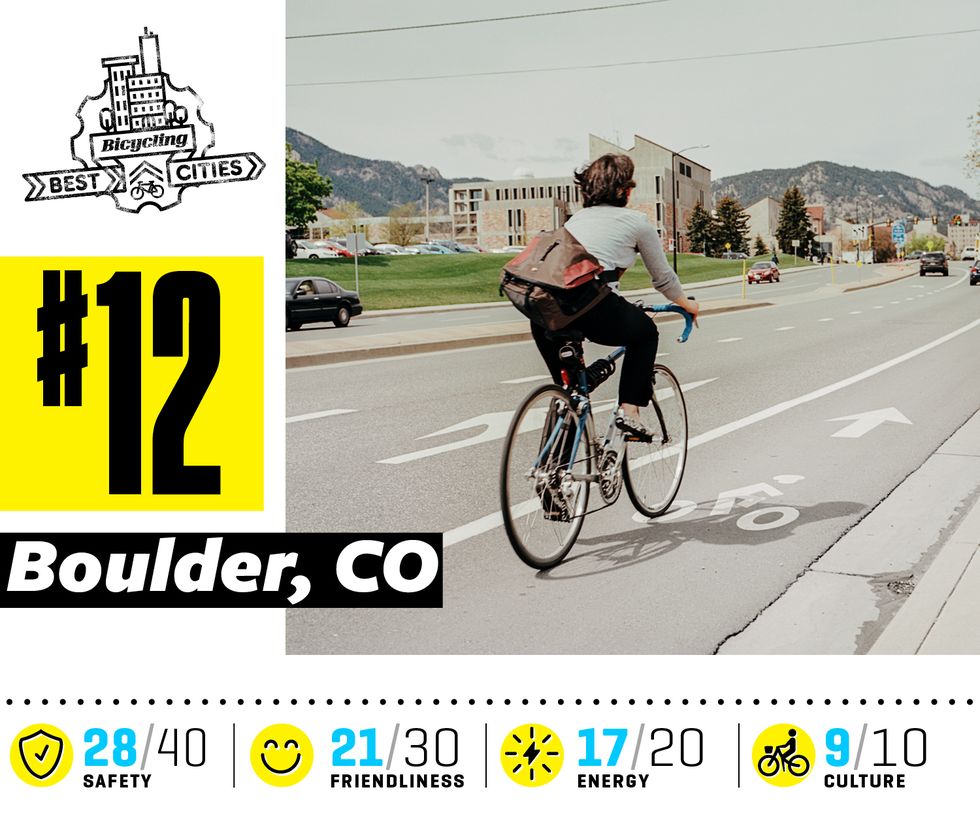

2016 Ranking: 10

Boulder’s protected bike lanes got off to a rocky start, when, in 2015, the city capitulated to the car lobby and removed several blocks of protected lanes on Folsom Avenue. For many bike advocates, it felt like waving the white flag and allowing the car-centric status quo to rule. But city transportation officials like Dave Kemp, say they’ve learned from their mistakes and that things are getting better.

Boulder now has four miles of protected bike lanes, and three and a half miles of buffered lanes. “There’s a great multi-use pathway system too,” says Sue Prant, director of Community Cycles, an advocacy organization in Boulder. Though she adds that throughout the city there are some missing links.

The city is trying to address those missing links, but many of them are in spots that require major engineering changes. “The projects that are left are pretty challenging; we’ve done all the low hanging fruit,” says Kemp. And despite Boulder’s “Gortex Vortex” reputation, it can still be surprisingly hard to get motorists on board with supporting bike infrastructure. The city is growing rapidly, and the increased traffic has many motorists lobbying for more room for cars—even though that’s an ultimately unsustainable fix.

Although the City of Boulder hasn’t had a bike fatality since 2016, the city’s other big struggle is a perception that it’s not a safe place to ride. This is, in part, due to several high-profile crashes that have happened just outside the city limits. While Boulder technically scores well on our safety category, we must acknowledge that no city exists in a vacuum, and if the rate of fatalities is high right outside city limits, that’s a problem for encouraging new riders.

2016 Ranking: 7

A recipient of one of the 10 Big Jump Grants from People For Bikes, Austin has a goal of doubling the number of people on bikes by 2020. To do that, however, is going to take a lot of work. “Right now, things are still pretty car-centric,” says Katie Smith Deolloz, executive director of Bike Austin. On some key bikeways, bike lanes are shared with parking lanes, and too many miles of infrastructure are just sharrows.

But Austin, with its rapid pace of growth, is a prime place for a bicycle revolution. “You can’t go a day without someone complaining about Austin’s parking or traffic problems,” says Deolloz. The city is firmly committed to easing that congestion problem via better biking and transit options, too. Since 2016—the last time we did these rankings—Austin has built 7.8 miles of protected bike lanes. That’s the most of any city on this list (although, San Fransisco is a close second with 7.7 miles).

Unlike other cities, which have avoided removing parking at all costs, Austin is plunging ahead with eliminating parking, even in key downtown areas. One of those projects is Guadalupe Avenue, one of the busiest streets in the city. In 2017, transportation planners proposed removing all the car parking in a 1-mile stretch, and taking out two vehicle lanes as well. The message this plan sent was clear: To keep Austin moving, we have to prioritize transit, pedestrians and cyclists—not cars.

One of Austin’s main challenges is its size. “Austin is a big place,” says Laura Dierenfield, the Active Transportation Program Manager for the city. And it’s sprawling outwards every day. To make biking work, especially for those living out in the exurbs, Austin is focusing on its bus rapid transit lines and encouraging the growth of bikeshare and scooter systems.

There are growing pains with expanding these systems, though. For example, Deolloz says she lost the bus line that used to run right by her house because it was consolidated with another route. “There’s this expectation that people will walk or bike the extra distance to catch another bus,” she says. While she’s been car free for years and will make the trek, she worries that those just entering the car free lifestyle may not.

2016 Ranking: 11

It always seems like Denver should be higher in our rankings—after all, recreational cycling is so popular among Denver’s outdoorsy residents. “Bike ownership here is really high,” says James Waddell, the executive director of Bike Denver. But there’s a difference between driving your bike out to the mountains on the weekend and using it as your main form of transportation. That’s something Denver still needs to work on. In fact, just 2.3 percent of Denver residents use that bike they own to get to work. “It’s still a really car-centric part of the country,” says Waddell.

The good news is that people living in Denver do seem to support more bike infrastructure. “There was a huge voter-driven bond initiative which provided a $900 million bond,” a large chunk of which will go to transportation and bike projects, says Dan Raines, a senior city planner for Denver County (which also oversees the city). He adds that the city’s current plan will put every household in Denver within a quarter mile of a low-stress bikeway by the year 2030.

Still, bike advocates feel like progress is too slow and the funding is too sparse. “It’s still vastly underfunded. To go from $2 million to $4 million on spending when what you really need is $20 million feels a little frustrating,” says Waddell.

Finally, like Boulder, there’s a real perception that cycling isn’t safe. How pervasive is this feeling? Well, it’s so pervasive that Denver’s bike cops won’t ride on the streets. A 5280 magazine piece interviewed a number of bike cops, all of whom said they vastly prefer riding on the sidewalks. If Denver’s finest are too afraid to take to the streets, what does that say for the rest of the city’s residents?

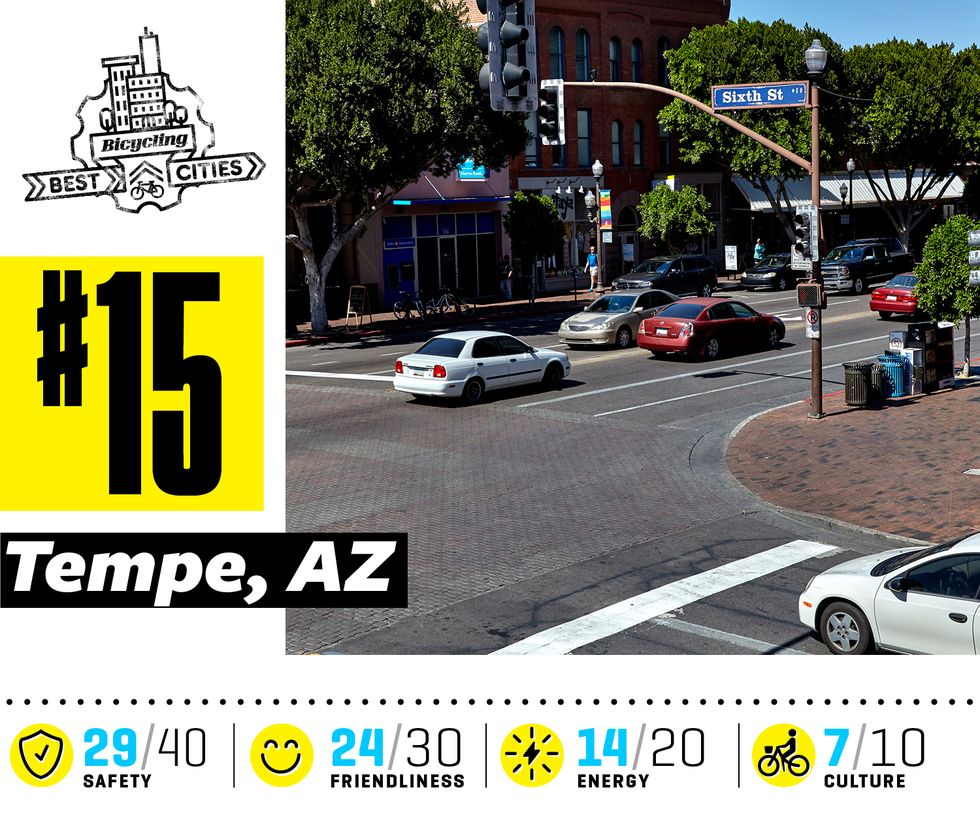

2016 Ranking: 22

Sprawling western cities tend to score poorly on our rankings. This is in part because the streets are often overbuilt, so heavy traffic isn’t an incentive for getting out of your car and onto a bike. It’s also because growth tends to roll outward for miles and miles, making the sheer distance you’d have to travel undoable for casual riders.

Tempe, however, seems to be bucking the trend. In part, that’s because it’s the highest density city in the state of Arizona. Still, it’s hot as hell and like most big Western cities, has its share of suburban streets that go nowhere.

“We’ve been really focused on building out our pathways program,” says Eric Iwersen, the transit manager for the City of Tempe Public Works. He adds that right now there are 38 miles of off-street paths crisscrossing the city.

Usage of the pathways has exceeded the city’s expectations, so Iwersen says there’s now an even greater push in the city to expand offerings. Planners are also trying to make intersections safer, with the installation of eight protected intersections. The building of several underpasses—so bikes can bypass intersections all together, is also underway.

We were forced to dock some points from Tempe since it’s one of several cities that has removed protected bike lanes. “There was a 3-and-a-half-mile project on McClintock Drive that drew quite a lot of public division,” says Iwersen. The result was that bikes lost, with drivers re-gaining a lane, and the bike lane being pushed to a mix of widened sidewalks and traditional bike lanes.

Still, the bike infrastructure that does exist is well built and—most importantly—designed to keep riders cool and comfortable. Iwersen says that there’s an effort underway to plant trees along Tempe’s bike routes, and to make riding the pathways as enjoyable as possible by adding neat public art and nice landscaping to every mile.

2016 Ranking: 14

This summer, Salt Lake City cut the ribbon on the completed Golden Spoke trail, which is the longest paved trail west of the Mississippi, says Becka Roolf, the active transportation planner for the city. A few new on-street facilities have been installed, too, including a 2.5-mile bikeway from downtown to the University of Utah. “It’s a mix of traditional bike lanes and bike boulevards,” says Roolf, adding that because the route climbs a steep hill, engineers gave riders three route options. The first (symbolized by green signage, like the ski slopes nearby) is the easiest with two low-key switchbacks. Then there’s a blue intermediate route. Finally, there’s a black diamond lung buster that goes straight up.

But Salt Lake City’s rapidly growing population is also going to present challenges in the years to come—especially with growing air pollution, which is already a real problem. Phil Sarnoff, who runs Bike Utah, says that if elected officials in the city don’t start making driving a whole lot less comfortable, drivers are going to do that for themselves—in other words, increases in traffic and low-air-quality days will soon make everyone miserable. The city’s new mayor ran on a platform of reducing smog, but so far, bike advocates are skeptical of her plan. “She’s made this huge push for making Salt Lake City carbon-neutral, but increasing biking is absent in the plan,” says Sarnoff. And the city isn’t incentivizing bike travel at the rate that cyclists would like. Still, the city has a better basic network than a lot of other places in the country, with more then 200 miles of bike lanes, plus a relatively low fatality rate, and a pretty robust bike culture.

2016 Ranking: 25

This D.C. suburb was one of those cities that, back in 2016, looked like it was poised to make a big jump up the rankings. Gaps in the network were being closed, and residents seemed to support multi-modal transit. “Arlington has been pretty good at making community bike routes accessible,” says Gillian Burgess, who sits on the Arlington Bike Advisory Committee, adding “and the trails really serve the commuting population well.”

But then came a series of budget blows. First, the Metro—DC’s subway system—needs major repairs, and Virginia and Maryland are footing the bill. That means state transportation funds that might have helped with bike route building have been diverted to train repairs. Secondly, several large government contractors and agencies have moved their offices out of the city. “So we have a high commercial vacancy rate,” says Burgess. The result is lower tax revenues—and therefore—less money to spend on bike lanes and pathways.

Still, Richard Viola, the bicycle and pedestrian programs manager for Arlington, says improvements are happening. He points to a recently completed two-way cycletrack near Ballston—a busy shopping and eating district in the city. He says the Arlington is also adding buffers to existing bike lanes to try and make routes more comfortable to all.

One of the neatest things currently happening in Arlington is a push to get public school teachers biking to school. In 2017, the county began incentivizing biking and carpooling for school employees. Now, schools have commuter lounges where teachers can change out of their bike clothes, and priority bike and carpool parking. The hope is that watching their teachers roll to work on two wheels will help kids think of bike commuting as normal and accessible.

2016 Ranking: 32

Minneapolis and Saint Paul may be twins, but Saint Paul doesn’t have quite the same infrastructure that Minneapolis does for one key reason: As the state’s capital, Saint Paul houses many government buildings—which don’t pay property taxes. “The city has significantly lower tax revenues,” says Andy Singer, co-chair of the Saint Paul Bike Coalition.

That’s made getting on-street infrastructure difficult. “Saint Paul didn’t even have a comprehensive bike plan until 2015,” says Singer. But, things are looking up. Since the bike plan was passed in 2015, the city has embarked on a number of new projects including two protected bike lanes and a protected, two-way cycletrack.

Singer also says that Saint Paul is blessed with an engaged citizenry and many elected officials who are pro-bike. “All we do is win with the city council right now. For a long time we had a problem where we never won, but now that’s changing.” Though funds may be limited, the city is improving bike lanes as it paves streets and is working to create more low-stress routes between its robust trail system. Look for Saint Paul to continue to climb up in these ranks in future years.

2016 Ranking: 21

One way to quickly grow your city’s bikability? Hire the guy that made New York City bike friendly. In 2017, Oakland hired Ryan Russo as its first permanent director of transportation, luring him away from the Big Apple. The goal, Russo says, is to catch up in bike friendliness with San Francisco, though Oakland has a long way to go.

Oakland plans to gain ground by having its very own department of transportation, something that few mid-sized cities actually have, says Russo, adding, “The mayor campaigned on the idea that managing the streets was an important thing for the city of Oakland.”

So far, managing the streets has meant moving bike lanes out of door zones, and adding buffers when possible. Oakland is also addressing dangerous intersections—especially around BART Stations, something residents say is badly needed.

Things aren’t perfect, of course. In May, the city was chastised for building a bike lane that was wickedly narrow and littered with drainage ditches. However, there’s lots happening in Oakland and we expect this to be another city that moves up in placing in the next two years.

2016 Ranking: 17

Boston has always had a lot of riders, thanks to its many colleges and lack of parking. But for years, those riders were relegated to sub-standard bike lanes, many of which were in door zones. Finally, things are changing, says Tom Francis, Deputy Director of MassBike. “Things are going remarkably well in a lot of ways,” he says adding that because downtown congestion is now so bad its hindering economic growth, city leaders are starting to get really serious about alternative travel modes.

That seriousness has resulted in a number of protected bike lanes, including protected lanes on the Longfellow Bridge, and down Beacon Street and Massachusetts Avenue, all of which are major thoroughfares. There are still connectivity issues in the network, says Francis, adding that big arterials seem to border many of the city’s prime greenspaces, making it hard to ride to and from some of the nicest spots in town. Still, overall the network is much better than it was even just a few years ago.

“Today, I’m more comfortable riding in the city of Boston than in the suburbs, which is not what I would have said 10 years ago,” he says. That’s in part due to the bike network, and in part due to the city changing speed limits to 25 miles per hour citywide. “It’s also hard to be distracted for long while driving in the city,” he adds.

Boston technically fell a bit in our rankings, in part because its fatality rate (3.1 per 10,000 riders) is significantly higher than any other city that made the top 20. If Boston can lower that rate and continue to improve the connectivity of its network, it will surely be a top bike city in no time.

2016 Ranking: 27

The City of Boise’s streets are actually owned and managed by the county, “so often it’s like, what is in our control to change?” says Jimmy Hallyburton, the executive director for Boise Bicycle Project, a community advocacy group. He adds, “But these past few years, the county has been really good at working with us.”

Boise is currently looking at 100 new bikeway projects, says Brooke Green, the bike and pedestrian coordinator for the Ada County Highway District. The goal is to build “a connected network of low-stress routes,” she adds.

From a recreational standpoint, Boise is a great place to ride, and what’s neat is that the city’s recreational riders are transitioning to transportation riders, too. Things like bike parks and mountain bike trails within riding distance of downtown have helped people see that riding to the trailhead makes more sense than driving. From there, Hallyburton says, people tend to start trying other errands on two wheels.

One of our favorite things about Boise’s bike scene right now is that ridership is extremely diverse. “Boise has a big refugee population, and the city has really embraced the refugee community,” says Hallyburton. Because it can take months for refugees to be able to get drivers’ licenses—or have the finances to buy a car—the Boise Bicycle Project helps by setting up refugees with bikes. It also teaches them to ride, if needed.

2016 Ranking: 19

A lot has changed in New Orleans since 2008, when the city put in its very first bike lane. Now there are 20 miles of shared-use pathways, 4.5 miles of protected bike lanes, and 45 miles of traditional lanes. In 2015, New Orleans opened the Lafitte Greenway, a 2.6-mile-long trail connecting NoLa’s Mid City and French Quarter.

Now, the goal is to add further connections, including one to Delgado Community College, the largest community college in the city. This will make biking a more attractive option for students, says Dwight Norton, the city’s mobility coordinator. “Right now we have great starter network to build off of,” he says. Thanks to a People For Bikes Jump Grant, the city has several plans for new routes. The focus for the future is downtown, because “that’s where most the jobs are,” says Norton.

“People have ridden their bikes in New Orleans in a traditional way—as a means of necessary transport—for a long time. But there’s been this perception, this stigma around riding. That’s finally starting to change,” says Norton. A diverse group of young cyclists has organized a weekly evening social ride called Get Up and Rid, where riders blare music from speakers and affix colorful lights to their bikes. It’s attracted up to 300 cyclists. And the bike share program, launched in December 2017, is growing beyond initial projections. “It took a couple of months, but then Mardi Gras got people trying it, and since then it’s taken off,” says Norton.

2016 Ranking: 29

Like the other college towns on our list, Gainesville’s modeshare is impressive (at least for America), with 5.1 percent of commuters using their bikes daily. But it has a safety issue. Averaging three bike fatalities for every 10,000 riders (per the League of American Bicyclists) is too many.

Chip Skinner, who works for the city’s department of transportation, says that Gainesville is trying to change that. “There’s a Vision Zero proposal in the works, and we look at every [road] construction process from a safety prospective.” Skinner says that Gainesville is also working hard to create bike boulevards, which offer riders a low-traffic alternative within a few blocks from a main arterial.

One neat thing Gainesville has done: Tweak the city building code to demand that every new construction project comes with a bike parking facility. It’s also working on making intersections safer by adding bike boxes and signals that can detect bikes.

Besides students, Gainesville’s thriving bike culture includes events like the annual Gainesville Cycling Festival, which includes the Santa Fe Century and a 65-mile gravel challenge; plus the silly-fun mountain bike trails at nearby Santos Trailhead. Mountain biking in Florida? Yes, it exists, and many of the best spots in the state are nearby.

2016 Ranking: 23

Tucson already has a terrific network of off-street paths, including the 130-mile Loop, which circles the city. Now the goal is making the on-street infrastructure as great as what’s happening off road. A 2017 Bicycle Masterplan will deliver 190 miles of new bike boulevards plus a few protected bike lanes, says Andrew Bemis, Bicycle and Pedestrian Program Coordinator for the city.

“Tucson has a strong and diverse culture for social riders and bike commuters,” he says, adding that the city is grooming a new generation of riders too, via a program called Riders & Walkers which teaches third graders how to bike and walk safely. It’s a great town for mountain biking too, with more than 100 miles of trail within a 20-minute drive from town.

While People For Bikes ranked Tucson high—fifth—on its list of best cities for cycling, and the League of American Bicyclists awarded it a gold rating, we just can’t put a city with an average of six fatalities per 10,000 riders (double the rate of even the next highest city in the top 25) any higher than 24th in the nation. Tucson has the bike culture, the beginnings of a truly great network, and tons of recreational opportunities for cyclists, but it needs to address its high fatality rate to really become a great bike city.

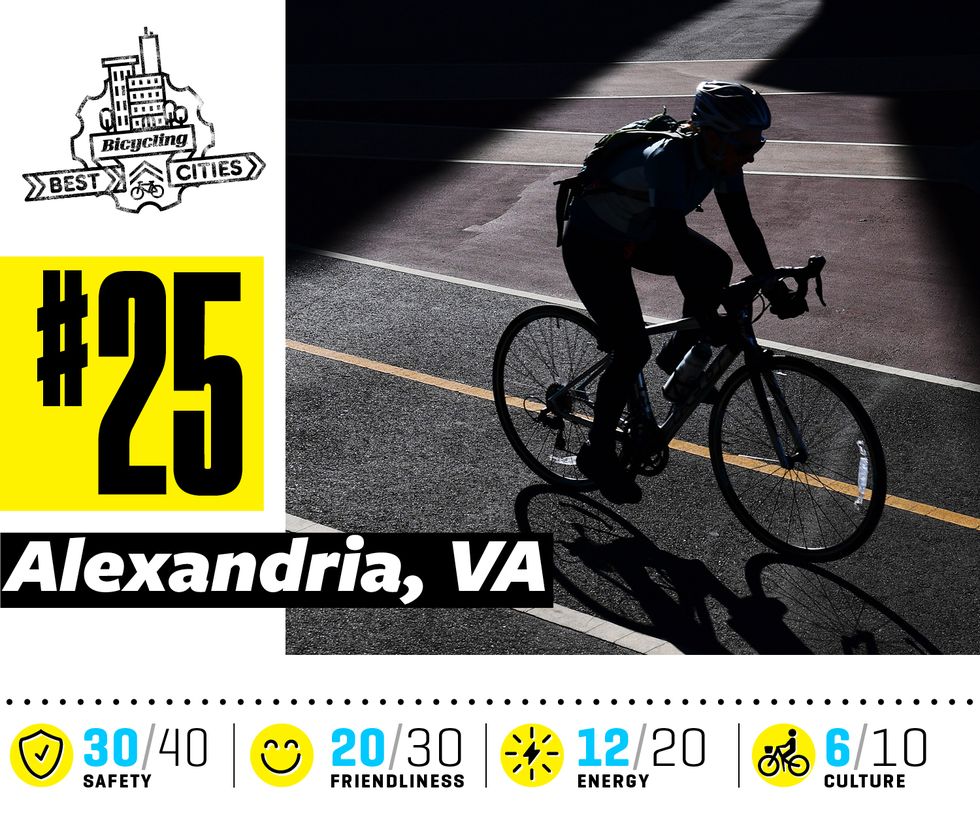

2016 Ranking: 34

This D.C. suburb is putting in the work to move up this list and should be even higher by the time the 2020 rankings roll around. In the past two years, Alexandria ratified a new bike and pedestrian plan, and a Vision Zero plan. The city has also added three employees who work extensively on bike and pedestrian projects, says Jim Durham, chair of the Alexandria Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory committee.

That’s just the groundwork, though. Now the hard part has to happen. Like Arlington and D.C., Alexandria has a good existing trail network that can move commuters into the city. But first- and last-mile connections leave something to be desired. And getting to and from places that aren’t served by this network means mostly riding in traditional bike lanes—just paint, few buffers and even fewer physical barriers. “Equity is also an issue,” say Durham. Alexandria’s West Side, which has traditionally been lower-income,hasn’t gotten the same amount of bike and pedestrian attention as the rest of the city.

Things are moving the right direction, though. Alexandria is taking safety seriously and has reduced speed limits, narrowed lanes—which slows traffic and forces drivers to be more careful—and built in speed cushions (which are flatter and less harsh than speed bumps) and curb bulb-outs to slow traffic. Moving forward, Durham says the focus will be on creating more neighborhood greenways to close gaps in the bike infrastructure—though to really bump this city up in this list, they’re going to need to get serious about building protected lanes too.

2016 Ranking: 15

Philadelphia has a lot working against it. First, the city’s historic streets are pencil-thin, and when they’re not, they turn into major thoroughfares with heavy volume and high speeds. Also, Philadelphia regularly tops the list as the poorest big city in America, meaning average wages, and thus property values and property taxes, are lower than in other places around the country. This keeps city coffers lean. But, it also keeps city employees creative. “One thing we’ve been really good at is getting grants,” says Kelley Yemen, the director of Philadelphia’s Complete Streets program, which works to make roads safer for bicyclists and pedestrians. Closing gaps in the 10-mile Schuylkill River Trail, which runs through and outside of the city, and adding a two-way cycle track on American Street, a main artery through town, are just two of several projects that came courtesy of ambitious grant writing.

Despite the city’s narrow streets, Philadelphia has put in 3.25 miles of protected bike lanes and 21 miles of buffered lanes. (Protected bike lanes have some sort of physical separation—like plastic bollards. Buffered lanes, generally have just an extra few feet of striping to keep cars away.) But some cyclists want more. “The three miles of protected bike lanes that have been installed are adequate for now, but we need the city to invest in long-term permanent solutions and move away from plastic bollards,” says Dena Driscoll, a car-free Philadelphian and avid bike commuter. Though Philadelphia’s streets are full of cyclists on any given weekday morning, and ridership is high, Driscoll’s sense is that the city still prioritizes cars over bikes.

Philadelphia has adopted a Vision Zero initiative and is currently working on fixing problem intersections, adding bike signals, and deploying traffic calming measures. One neat project raised the entire intersection at Chestnut and Walnut Streets: Not only does the bump in the road slow down vehicles, but it makes the crossing safer for pedestrians and people with disabilities, since it also raises the pedestrians up so they’re at eye level, says Yemen. Plus, changes in road conditions tend to force drivers to pay attention—meaning they’re more likely to see cyclists than they otherwise might be.

2016 Ranking: 28

In 2017, Long Beach finally updated its Bicycle Master Plan, with an ambitious goal of adding protected facilities all the way across the city. That’s still in its very early stages, with the city applying for funding, says Michelle Mowry, the Mobility and Healthy Living Coordinator for the city, but she says that three miles of protected lanes are already in and 3.8 more are on their way to being completed.

Despite much of Southern California being totally car-dependent, folks in Long Beach are embracing bike projects, and Mowry says there’s been relatively little pushback against road diets (removing a car lane to give more space to bikes). There’s also been widespread support for projects like separating the bike lane from a new pedestrian lane on the local San Gabriel River Trail, which improved the experience for both user groups.

Finally, a growing bike share program, and a bike parking program that provides free racks to businesses and communities, is making the city even more friendly to cyclists. If Long Beach sticks to its ambitions 2017 plan, we expect to see it moving up the ranks in coming years.

2016 Ranking: 66

You’d think the home to the Olympic Training Center would be a cyclist’s paradise, but that’s not always the case. “Colorado Springs’s motto is ‘Olympic City USA,’ and cycling has always been a part of that, but when it comes to using bikes as transportation, there’s still a lot of work to be done,” says Cully Radvillas, who works with Bike Colorado Springs. “I commute by bike and I can actually ride singletrack as part of my commute,” he says, but on-street infrastructure is lacking. “We’re working to change the culture so biking is a way of life.”

Since 2016, the city has installed 1.25 miles of protected bike lanes and 8.43 miles of lanes with buffers. However, some pilot project buffered lanes were taken out after motorist outcry, which Radvillas says was a real bummer—especially in a city with relatively light traffic and little parking trouble. On the plus side, Colorado Springs instituted a bike share program this year, with a second phase bringing more bikes and stations in 2019.

The biggest challenge for making Colorado Springs commuter-friendly is the city’s sheer size, says Radvillas. “We’re 220 square miles and laid out in a really car-centric way.” Hopefully with the growing bike share and more lanes going in, some of the city’s many recreational riders can be converted to making around town trips by bike too.

2016 Ranking: 41

The Cuyahoga River splits the city of Cleveland in half, and for years, bridge crossings were perilous for cyclists. Finally, that’s changing. A massive project on the Detroit Superior Bridge gave Cleveland cyclists their first protected bike lanes, shielding riders from fast-moving trucks and cars. “This is the culmination of a project that was planned 15 years ago,” says Jacob VanSickle, Bike Cleveland’s executive director. It’s not perfect— the west-bound lanes are still not protected, but between the bike boxes at traffic lights and bike-specific signals, and the protected lanes on the eastbound side, the project feels like solid progress.

Around town, painted bike lanes are popping up, especially near the entrances and exits of the area’s many off-street pathways. “We’re focusing on commuter corridors and now there’s much more of an ability to get around on them,” says Calley Mersmann, the bicycle and pedestrian coordinator for the city. VanSickle says that when it comes to downtown roadways, cars have previously taken priority, and getting parking removed or lanes taken away can be a fight. However, that’s also changing: “In the last five to six years we’ve taken more roadway away from cars and people are starting to realize it isn’t the apocalypse.”

2016 Ranking: 13

The glittering crown jewel of the Indianapolis cycling network is its Cultural Trail, an 8-mile, separated loop that shows off some of Indy’s best downtown spots. Its public art and lovely landscaping have made it a hit with tourists. But for locals trying to get around the city, it’s just one tiny piece of a somewhat fragmented network. “Indy has about 100 miles of greenways and 100 miles of bike lanes,” says Damon Richards, the interim executive director of IndyCog, the local advocacy group. He adds that folks on the south side of the city—a traditionally underserved area—have a particularly treacherous route into the city with few safe route options.

Things are, however, still better than they were a decade ago. Indianapolis has added three more miles of protected bike lanes in the past two years, plus 12 miles of off-road pathways, and has big plans for tripling the miles of protected lanes over the next 10-15 years. But like many cities in the Midwest and West, there’s plenty of room on roads and little traffic—which makes it hard for bike advocates to push for serious investments in bike infrastructure, says Richards.

2016 Ranking: 60

Equity of funding for all neighborhoods is something every city on this list is trying to address. But just introducing a bike lane in a poor neighborhood doesn’t necessary solve problems In fact, for many in low-income areas, bike lanes are the first indication that gentrification is on its way.

“Almost 25 percent of the population of Memphis lives below the poverty line, so equity is a permanent issue here,” says Nicholas Oyler, manager of the City of Memphis Bikeways and Pedestrian Program. “Many of our residents are biking and walking out of necessity.” Instead of just painting on a bike lane, though, Oyler and his colleagues set up a series of meetings in different neighborhoods to ask what residents wanted. It turns out that better pedestrian infrastructure was what people in lower-income areas really needed, and until it felt safe to walk through the neighborhoods, residents were wary of adding bike lanes too.

In areas where residents are asking for bike infrastructure, the city is delivering. Oyler says Memphis introduced Tennessee’s first bike-specific traffic signal and is using a federal grant to install 1,000 new bike racks near transit facilities. It’s also a recipient of one of People For Bikes’ Big Jump grants, and is using that money to help fund a teenage bike ambassador program.

2016 Ranking: 37

In 2017, California began using gas taxes to build active transportation projects, and Sacramento is one of the cities reaping its benefits. Improvements—like widening bike lanes, or building protected lanes and two-way cycle-tracks—are in progress, and, according to the department of transportation, there’s a focus on adding facilities to low-income neighborhoods.

But these are just baby steps toward solving one of Sacramento’s biggest issues: Streets are much less safe in neighborhoods of color, and local police practices aren’t helping at all. In late July of 2018, a police officer actually hit a young black teen after pulling him over on his bike for not having a head light. One other big problem in Sacramento is its bike fatalities. Averaging 5.7 fatalities per 10,000 riders, it was in the top 15 for most fatalities out of all the cities on this list.

2016 Ranking: 53

The city is taking its bike-friendly businesses program seriously. In just a few years’ time, Saint Petersburg has gone from two businesses certified “bike friendly” by League of American Bicyclists to 20 bike-friendly workplaces that incentivize bike commuting and there’s also a Complete Streets policy in place, though the city is far from achieving Vision Zero: Its fatality rate is 6.8 per 10,000 riders. Open streets events (where streets are temporarily closed to cars) are also hugely popular and successful, and are helping to change discussions in the community about what a street should be and for whom it should be built.

With constant warm weather and flat roads, Saint Petersburg should be a cycling paradise, but like many other Florida cities, its fatality rate is too high for it to be truly great. Still, it has some promising initiatives in place.

2016 Ranking: N/A

Making its debut on our list for the first time, Richmond, Virginia has made a big commitment to building connected, protected bikeways. In mid-2018, the city unveiled its first protected two-way cycle-track, which spans one mile of downtown real estate. Even better, it connects a popular off-road bike path—the Virginia Capital Trail—with a bike boulevard that takes cyclists into a major shopping and dining district. “It’s three miles of contiguous low-stress network through one of the densest parts of the city,” says Max Hepp Buchanan, the head of Bike Walk RVA.

Richmond is also working on creating safer bridge crossings for cyclists, with the opening of a bike- and ped-only bridge over the James River and buffered bike lanes being added to two other bridges in town. In addition to the city’s Bus Rapid Transit lines, it has a growing bike share program (with e-bikes coming soon). It’s easy to see Richmond is remaking itself into a great bike city.

2016 Ranking: 44

Lincoln is in the midst of generating a new citywide bike plan, but is already celebrating a few successes. Its bikeshare program, which launched last April, was a big hit in its first few months. “We started with 100 bikes and in the first month we logged 2,200 rides,” says Sarah Knight, vice president of the board of directors for BicycLincoln. She adds that although the stations are clustered downtown, she’s seeing a surprising number of bikes outside the city core, meaning that people are using them for more than just five-minute trips.

“Overall Lincoln does recreation really well,” says Knight, adding that there are 248 miles of off-street pathways in the city and surrounding areas. “But we need to do more on the transportation side,” she says. Unfortunately, the political will to get that done is somewhat lacking. “There are a lot of people who don’t like seeing bikes on streets,” she says.

Lincoln did get its first protected two-way cycle-track in 2016, which runs the length of N Street in downtown, but it’s the Lonesome George of protected infrastructure in Lincoln. The city mostly relies on sharrows to move cyclists around—something it will need to improve to climb this list.

2016 Ranking: 46

Over the summer, Milwaukee got its first protected bike lanes, which connect several local trails systems with the busiest parts of town, including UW Milwaukee. Several other protected bike lanes are now in the works, as are a few bike boulevards. These new low-stress streets join an already solid network of bike lanes. As the city of Milwaukee’s population has dropped, the city has done something unique: It’s used the lowered car volume on its streets to increase the room allocated to bikes.

Like many other Midwestern cities, Milwaukee is sprawling, so transportation engineers know bike lanes alone won’t fix their city’s low ridership rates. That’s why Milwaukee is working on an impressive Bus Rapid Transit line, which will traverse a nine-mile corridor, encouraging more bus ridership and first-and-last-mile commuters.

One of Milwaukee’s ongoing challenges is equity, which plagues many cities on this list. But one way it’s addressing that is the city-wide program teaching more than 2,000 school kids each year how to ride. City officials are also ace grant writers, and Milwaukee was recently awarded several state alternative transportation grants, which will hopefully help grow its network even more.

2016 Ranking: 31

Louisville has invested its energy in buffered bike lanes, which may become protected lanes in the future. “We’re going to try putting up posts for protection, but they seem to be working well without them,” says Rolf Eisinger, the bike and pedestrian coordinator for the city. Still, a huge chunk of Louisville’s bike real estate is simply sharrows (there are 111 miles of sharrow lanes), which badly need upgrading.

The city is working to develop its recreational cycling opportunities, by building an 18 mile shared-use path in a 4,000 acre urban park, and the construction of the Louisville Loop, a 100-mile off-street pathway around the city. However, “it’s not even close to finished. About a quarter of it has been completed,” says Chris Glasser, the Executive Director of Bike Louisville.

Like many cities, bike funding seems plentiful in early budget meetings, but Glasser says that all too often the original number promised doesn’t match the amount allocated at the end of the process. And that’s slowing Louisville down from becoming a truly great American bike city.

2016 Ranking: 51

In 2017, Des Moines announced a $33 million dollar downtown overhaul aimed at slowing traffic and making facilities safer for cyclists and pedestrians, which energized activists and cycling residents in Iowa’s capital city. Still, the projects take time, and as of the publishing of these ranking, the city only has one mile of protected bike lanes established. More are coming though, as are more traffic-calming measures like speed tables, chicanes, and redistribution of car lane space for wider bike infrastructure.

Also promising is that the city hired its first-ever bike and pedestrian transportation manager, thanks to a property tax increase which funded the position. These things are making Des Moines a safer place to commute by bike, and the city is certainly laying the groundwork to build a better network.

2016 Ranking: 39

What happens when you ask a traffic engineer to go riding with you? “They see the street differently and understand why a design does or doesn’t work,” says Catherine Girves, the executive director of Yay Bikes!, Columbus’s advocacy group. In 2013, a local DOT official asked Girves for feedback on a project. Girves suggested to the official that they go experience the streets as cyclists—and actually see and feel how the design could be improved. In some cases that meant moving bike lanes out of drain-studded gutters. In others it meant creating better ways for bikes to navigate turning cars. Columbus’s first “professional development ride” was born, and now it’s a regular part of the state’s bike infrastructure design process. “It was like we watched a lightbulb go off,” she says of witnessing the engineers navigating sub-par bike lanes strewn with glass and drainage grates. Columbus started the program, but now Girves and her colleague travel all over Ohio doing “professional development rides” with various city DOTs.

There are other positive trends in the Columbus bike community, too. One is that women and people of color are well-represented among the city’s leading bike and transportation advocates. Another is that the city’s police chief is a cyclist who rides regularly on the roads. “It’s been amazing to have a chief that ‘gets it,’” says Girves. In terms of mileage, Columbus also has the most off-street pathways of any city in our survey, offering 180 car-free miles. Finally, the city has three, yes, three bike share programs, including one that offers adult trikes and side-by-side bikes for riders with disabilities.

2016 Ranking: 20

Like many other University towns, Pittsburgh boasts a relatively high modeshare, and a vibrant bike culture. Even steep hills and harsh winters don’t deter riders. But the city could use more infrastructure—especially protected bike lanes.

“We’ve gotten a lot of the low hanging fruit already,” says Eric Boerer, the advocacy director for Bike PGH, adding that now it’s time to connect those small pieces into one comprehensive, cross-town network. The city has successfully navigated a few road diets, which have resulted in slower vehicular traffic and more room for bikes—both big wins. And, now, several pushes are in place to extend protected lanes and redesign major downtown corridors. “We’re seeing some pretty big changes,” says Boerer. The city is also working towards closing the final connection on the Great Allegheny Passage, a bike trail that connects from Pittsburgh all the way to Washington D.C.

One thing Pittsburgh riders do have to contend with is Uber’s autonomous vehicle program, which tests such vehicles around the city. Though Uber stopped testing autonomous vehicles for a spell after one killed a pedestrian in Arizona, the cars are now back on the road, and Bike PGH is watching them warily.

2016 Ranking: 30

Chattanooga is a great bike town for recreation. The city believes outdoor tourism is its next big economic driver and has invested in mountain bike trails and bike parks within riding distance of downtown. Plus, there are miles of pristine road riding in the local hills, and a 12-mile-long Riverwalk that’s only open to bikes and pedestrians.

At least for now, the cost of living is low, and young families are flocking to the city, giving it an energetic and fun vibe. But for transportation, it's less idyllic. "There are a lot of bike lanes, but they don’t connect well,” says Aaron Cole, the co-chairman of Bike Walk Chattanooga. And, while there’s momentum to add bike lanes in the city itself, as soon as you hit county roadways, the bike friendliness evaporates.

Bikeways also aren’t always spread equally through neighborhoods. “Equity is our biggest challenge,” says Cole, adding that he’d love to see more and better sidewalks and pathways in low-income neighborhoods.

2016 Ranking: 43

Atlanta is huge, ringed by sprawling suburbs which makes comprehensive bike planning tricky. “There are 13 counties that surround the city, and they’re starting to do more for cycling, but they’re still pretty behind,” says Rebecca Serna, an advocate with the Atlanta Bicycle Coalition. The good news is that increased funding of the local bus system is helping move cyclists into the city, where a better network awaits.

That network still isn’t perfect, but it’s getting there, says Serna, and should improve more in the next few years. “A lot of projects that have been in the queue for a while are finally funded,” she says. Whether those projects will actually be completed is another issue. In 2017, the city removed a two-way bike lane and replaced it with car parking—even though REI and People For Bikes had provided grants for the lane. “It’s a street by street conversation,” says Serna on whether bikes are welcome or not.

Another big issue facing the city is equity. “The places where car ownership is lowest are where the streets are most dangerous for walking and biking,” says Serna. While conversations are happening around improving facilities in these places, it’s happening too slowly, and, as of this writing, Atlanta was still debating becoming a Vision Zero city.

2016 Ranking: 26

San Jose is a city to watch for in future rankings. This summer, the city broke ground on a project dubbed “Better Bikeways San Jose.” Piggybacking on its resurfacing projects, the city is adding a complete network of protected lanes that feed into low-stress bike boulevards. “It’s incredible actually,” says Shiloh Ballard, the executive director of the Silicon Valley Bike Coalition. She adds, “It’s all happening super-fast, from planning to design to implementation.”

Once these lanes are in, we fully expect to see San Jose continue to move up this list. However, right now fatalities (7.1 per 10,000 riders according to the League of American Bicyclists) are too high and modeshare (just under one percent) is too low to make this a great city for cycling.

The energy, however, is definitely in the right place. Ballard says the city set a 2040 goal of 15 percent modeshare for bikes, and the opening of a Google office in the city promises to add more good bike vibes, since the company actively works to promote alternative transit for its employees. Finally, Ballard says that San Jose also has the luxury of having a bike-friendly mayor and city council. With these pieces in play, San Jose may shoot to the top of our list in the next few years.

2016 Ranking: 38

Right now, Florida’s capital city is focusing on connecting major trails and off-street paths. "Within a few months, we will have a trail system connecting Downtown Tallahassee, Cascades Park, Florida State University, Florida A&M University, College Town, Gaines Street and a regional trail system that goes south to the Gulf of Mexico,” says Artie White, who works for the city’s planning department.

While Tallahassee isn’t going to win any awards for most protected or buffered lanes per mile, it is trying to improve the lanes it has, by widening buffers, and adding protection. Residents also seem willing to support bike infrastructure. A local sales tax hike is granting $1.5 million for bike lanes and trails improvements.

Finally, White says the bike culture in Tallahassee is surprisingly robust. Local riding clubs care for the bike lanes, offer all manor of group rides, and keep bike co-ops and community bike shops going. Even better: “Cycling initiatives in the city are developed and led by people who cycle," says White. "The majority of the staff in the Planning Department consider themselves cyclists.”

2016 Ranking: 51

Finally, a city that tells it like it is: “Our cyclists don’t like sharrows, so we’re transitioning away from them,” says Stephen Osberg a city planner for Omaha. In their place is a mix of regular bike lanes and efforts to move cyclists to lower-stress streets using wayfinding signs.

Omaha has also tackled several difficult road diets on arterials, slimming streets from four lanes to three and adding adequately sized bike lanes. And while Omaha has so far only made modest investments in protected bike lanes, it promises significantly more lanes before 2020. Those new lanes, plus the existing 85 miles of off-street pathways, should make for a good network by the time this decade is over.

2016 Ranking: 42

In 2006, Columbia received a federal grant aimed at improving bike transit, which kickstarted the city's momentum. “Columbia is now one of the leading cities in the Midwest for bike infrastructure,” says Brent Jugh, the executive director of the Missouri Bicycle and Pedestrian Federation. With that grant money, the city built a network of off-street pathways.

It’s not a perfect system yet. Angela Peterson, who commutes to her job at Cyclex Bike Shop, says, "there are still parts of the system that aren’t well connected.” Though the city tells us remedying that is its next goal.

The main reason Columbia isn’t higher on this list this year is its lack of protected lanes. There’s not a single one built or planned for construction between now and 2020. As great as off-road pathways are, we still need safe routes to get people from the pathways to their final destinations.

2016 Ranking: 35

With glorious weather and overbuilt streets that could easily host bike lanes, Albuquerque should be a top bike city. But it has a stubbornly high fatality rate for a city its size (five deaths for every 10,000 bike commuters, on average), and some bike lanes are subpar. One on Girard Boulevard, for example, is so narrow not even the full bike stencil fit into the lane.

Still, progress is being made, says Ann Overstreet, vice president of Bike ABQ, the local advocacy organization. “In the last few years we’ve had a lot of continuation on existing projects,” she says, pointing to improvements to multi-use paths, adding small sectors of connectivity between popular routes, and investing in green paint and bike boxes at intersections. There have been road diets too, though the public reception has been mixed.

Albuquerque’s real challenge may be that it’s a sprawling and hilly city. While that isn’t a barrier to an experienced cyclist, it is for a newbie. The city seems to recognize mass transit’s key role in making Albuquerque less car dependent and implemented a bus rapid transit project on old Route 66. So far, it’s been a hit, with one of the highest ridership rates for a new BRT line in the country. As more residents realize they can zip across town sans car, look for more riders using bikes to travel their first and last miles.

2016 Ranking: 45

Tampa is one of the deadliest cities for cyclists and walkers. So how did it make the cut for this list? The first step to dealing with a problem is recognizing you have one, and Tampa seems to be doing that. It's the pilot city for a Florida initiative to slow speed limits in an effort to reduce bike and pedestrian deaths. Tampa has also narrowed its lanes and installed roundabouts and landscaping to slow drivers. It’s also adopted a Vision Zero initiative.

While these are great, concrete steps, Tampa Bay’s main bike network still needs work. Right now it’s is made up of off-road pathways and 9.2 miles of buffered bike lanes. We’d love to see more than 1.5 miles of protected bike lanes, especially in a place where fatalities are far too high.

2016 Ranking: 60

Five years ago, this university town hired its first dedicated bike and pedestrian planner, and since then, Knoxville has steadily improved. Now, there’s a comprehensive bike plan in place and every resurfacing project is seen as an opportunity to build in bike lanes, says Jim Hagerman, who works for the city. However, “We’re still a little late to the game and we have a lot of built in challenges,” he says, like the fact that the streets don’t have much extra space—especially when the University of Tennessee is in session. Still, “we have gotten bike lanes on roads I never would have thought possible,” says Kelly Segars a principal planner for the Knoxville Metropolitan Planning Organization.

While Knoxville may not have as many bike lanes as the top cities, it's hosting a research project which could make a big difference for cyclists everywhere. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration is using the city as a testing grounds for a safe passing law study. “The police department will be actively enforcing the safe passing law using a 3 foot detection device that uses sonar. Meanwhile a group of civilians will be riding with these detection devices outfitted on bikes to gather data on motorists behavior,” says Amy Johnson, a cyclist, advocate, and bike-focused lawyer in the community. The goal is to see exactly how effective 3-foot laws are, and to come up with innovative ways to make bikes safer against side swipes.

Knoxville is also working hard to make itself a prime recreational destination. The city created mountain bike trails within riding distance of town, and it's close to world-class road riding in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

2016 Ranking: 40

Finally, after years of begging and pleading, Miami is making its bridges safer for cyclists. Slowly it’s been revamping the Rickenbacker Causeway to Key Biscayne “which thousands of cyclists ride every day,” says Rydel Deed, bike advocate and author of TheMiamiBikeScene.com. Now, the causeway has green paint demarcating the bike lanes, plus rumble strips that alert drivers they’re too close. The city is also putting in non-slip grates over bridge joints—something cyclists have asked for for years.

Part of what’s helping move Miami forward is the bike-friendly mayor, Francis Suarez. “The new mayor recently led a bike ride along the existing Commodore Trail. The trail is in need of repairs and the ride was to raise awareness,” says Deed. Still, the city is sprawling and there’s a lack of connectivity within its bike network.

That’s not squashing enthusiasm though, says Deed. Critical mass rides can bring upwards of 2,500 riders, and Miami Beach’s Ciclovia events are even more popular. Plus, big long-term projects are in the works. One we are especially excited about is the Underline, an effort to transform 10 miles of metro-rail underpass into safe, enjoyable bike and pedestrian routes.