They are at the track, making hand gestures to each other. Alise Willoughby is atop the start ramp, helmet and goggles on, ready to roll into the gate for another practice run. And from his vantage point off to the side, Sam Willoughby, an Olympic medalist who is her husband and coach, is watching her and a few of the other riders he trains. It is exactly six weeks until the BMX competition at the Tokyo Games begins—time to fine-tune all the little things that add up to a big performance.

The sunlight is still severe at 4 p.m. at the Elite Athlete Training Center in Chula Vista, California, a sprawling, bucolic campus for Olympic-caliber athletes located 10 minutes from the Mexican border. Among chirping birds and the swaying fronds of well-manicured palm trees, clusters of hyperfit young men and women are sauntering around, chatting and laughing. But over at the BMX test track, long, intensely quiet periods of stasis are punctuated by brief explosions of action.

Sam pulls out a camera with a long lens and starts filming. Alise and her training partner, Lauren Reynolds, are running through their pre-ride rituals, which fill the minute before the gate drops. Alise jumps up and down over her purple bike, punches her quads and thighs, cracks her knuckles, and otherwise releases energy like she’s about to enter the ring for a prizefight. (“It’s a routine to feel ready,” she’ll explain after practice. “It’s something to distract me and keep me in the moment.”) Then, suddenly calm, she sits on the saddle, backpedals until her right foot is at 3 o’clock, loads the pedals, and waits for the count. Once BMX racers are in this position, a mechanized set of instructions are offered and then the gate drops randomly within a 2.7-second window.

When the gate falls, Alise explodes downhill. Her brown ponytail, which spills out the back of her helmet, is suddenly horizontal. She’s down the ramp, which is roughly 24 feet tall and 36 feet long, in less than three seconds. Her head and shoulders are still, driving forward, and she’s spinning a cadence that would make an elite track cyclist blush. There are numerous qualities that make Alise a world-class BMX rider, but her explosiveness out of the gate—she can crank out roughly 1,600 watts as she hits a cadence of 200 rpm in the first 2.5 seconds of a race—is an excellent place to start. Alise is relatively small for a top BMX racer—she’s 5′2″—but when she’s on the bike flying, it’s hard to notice with the power on display.

The opening stretch of the track here in Chula Vista has been adapted to closely mimic the course in Tokyo. Sam continues filming as Alise and Lauren, both athletes he trains, fly over a series of jumps. I’ve never seen elite BMX racing in person, and the fluidity with which these riders float through jumps at speed is startling. And in the Olympics, it’s eight riders doing this side by side, without lanes, as the world watches.

Within 15 seconds, the drill is over and Alise and Lauren soft-pedal back to the ramp. Meanwhile, Sam eyeballs the camera screen like it’s a microscope, studying both athletes: their head positions, the way their bodies coil and uncoil, the fluidity of their pedal strokes, the stillness of their shoulders. These are the little things that Sam Willoughby has thought very hard about for the past 20 years.

This is probably as good a time as any to mention that Sam is in a wheelchair. It’s also probably a good time to mention that Sam has long blond hair that shimmers in the desert sunlight and a dulcet Australian accent and softball-sized biceps. He’s like a medium-sized Thor. Sam had told me beforehand that he feels completely at ease at the track, and sure enough, that seems true during this practice session. You would never know that this is where Sam fell on his head in 2016 and suffered a spinal fracture that changed the arc of his life—and Alise’s.

But don’t worry: This story is not a tragedy. There’s tragedy and loss and heartbreak in it for sure, but it’s more uplifting than that. There will be races won and races botched and decades of hard work and a quest—one that’s still ongoing—to bring modern training techniques to a rebel cycling discipline, to turn silver into gold. But this isn’t really a bike racing story either. It’s deeper than that.

Alise rolls over to the flat strip of dirt where Sam is stationed. He pulls out the camera and she watches a little footage. The air is still and soundless and I am five or six feet away, but I simply cannot hear what Sam says to Alise. He says something quietly and she stares at the camera again. And then she nods, touches his shoulder gently, puts her helmet back on, and rolls back toward the gate. Sam just looks out toward the tight undulations of the track’s aptly named rhythm section with an intent smile.

I really don’t know what I just saw. But it’s starting to dawn on me that I’m writing a love story.

They’ve been at this a long time.

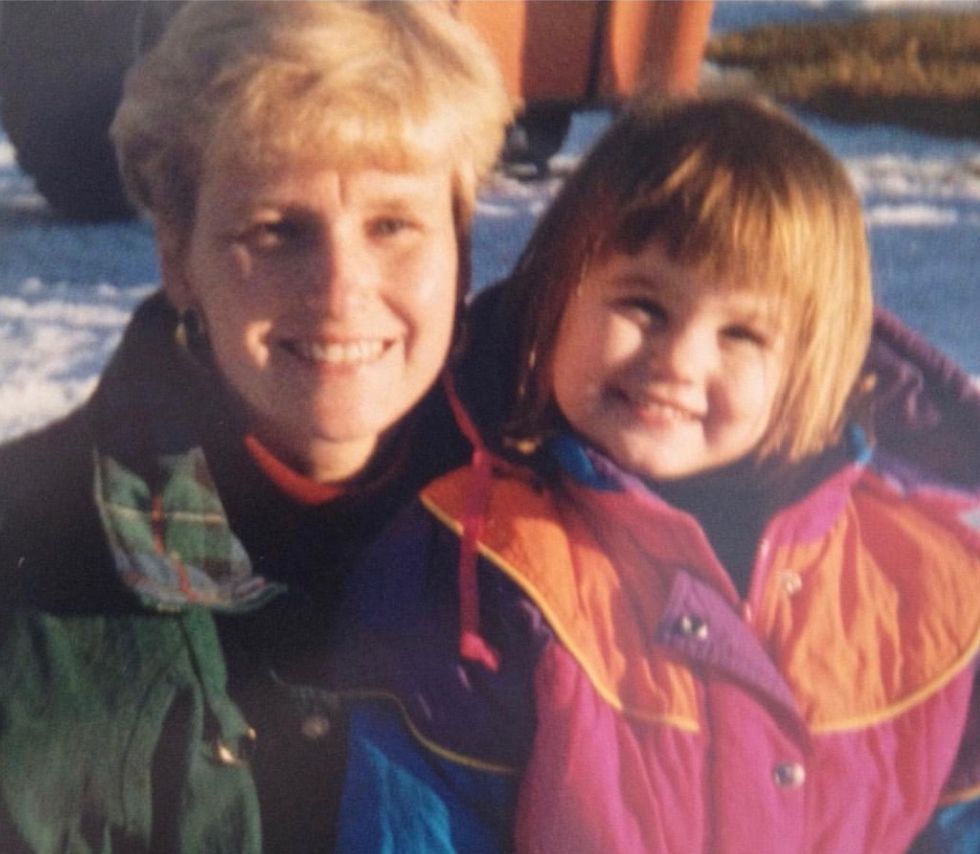

Alise Post Willoughby, now 30, got into BMX when she was 6. The first time she went to a race and saw the starting ramp and the jumps, she chickened out. But she came back the next week. “I had a little spill, got that out of my system, and everything was fine,” she recalls. “The rest is history.”

It’s a family history. For a while, the family piled into the minivan every Tuesday and drove an hour from their home in St. Cloud, Minnesota to the nearest track so Alise and her brother, Nick, could race. After about a year of this commute, Nick asked his parents if it was possible to build a BMX track in their hometown. Given that neither adult was a rider or had track-building experience, it seemed like a pretty big ask.

But Mark and Cheryl Post were not the sort to screw around. They began searching for a location, and after negotiating with the city of St. Cloud, took possession of a glass-strewn park with a vandalized building. Hundreds of truckloads of dirt and a volunteer workforce transformed Pineview Park into a local mecca for BMX kids. More than 20 years after the first race was held there, Mark Post still runs Pineview.

Alise, clearly an extraordinary athlete and already a standout gymnast, showed promise immediately. Mark remembers the time he took his daughter to a race when she was 9 and someone stole his van and trailer. “She jumped on some 5-year-old’s bike and won,” he recalls. “I told her I would take her to nationals until she lost.” That year, she was number one in the country.

At an age when most kids are still floating in the moment, Alise had clear ambitions. In the fourth-grade scrapbook she recently unearthed, there is a time capsule she prepared at the time. “It asked us to write what we wanted to be when we grew up,” she says. “I wrote that I want to be an Olympic pro BMX racer or something that makes a lot of money.” This was seven years before BMX debuted in Beijing. As it turns out, she’s happy with her choice.

Meanwhile, some 10,000 miles away, a towheaded boy in Australia was taking his first spin on a BMX bike. He was 4. Like his future spouse, who’d gotten cold feet on her first day at the track, Sam had an imperfect start. “The second or third week I was getting beat, so I threw my bike down on the track and stormed off,” he says, laughing. “My mom said I needed to learn how to lose before I could start racing again.”

By the time he was ready to try again two years later, Sam was already enjoying a childhood centered around bikes in his hometown of Adelaide, arguably the cycling capital of Australia. “My brother Matt and I were pretty good right away, because we rode morning and night,” he says, recalling bike racks at school that were always full. “On holidays we could ride from our house all the way down south, which is like a 30-minute drive. There’d be jumps and half pipes along the way, and we’d stop at them all.”

Much like Alise and her brother had done, Sam and Matt appealed to their parents to help them find a suitable place to ride. Sam’s father was obsessive about maintaining a flawless lawn at their suburban home, but he agreed to rip the whole thing out to build a BMX track. “We dug it up pretty good,” Sam says. “We had jumps and a berm and it looped around the front yard and around the clothesline in the back.”

When you throw together obsessive, talented kids with extraordinarily supportive parents, magical things can happen. By the time their tween years were over, both Sam and Alise were world-class juniors on the rise. And their stories were about to collide.

Simply asking these two when and how they met begins a 20-minute comedy routine with playful jousting and lots of sly smiles. It’s very safe to say that Alise was on Sam’s radar first. This was around 2005—Sam, the Aussie, had seen Alise in BMX magazines and on DVDs. “I guess I had a crush on her,” he admits. “I sent her a few messages on Myspace and she didn’t reply much.”

They briefly met in person in 2006—at the World Championships in Brazil—and for a hot second they were going to trade jerseys. But it didn’t work out there, or at the next World Championships in Canada. All the while, Sam kept messaging Alise on Myspace. “She blew me off many times,” he notes as Alise blushes.

They didn’t truly connect until 2008. Theirs was a typical teenage melodrama, only with locations out of a James Bond film. This episode unfolded at the World Championships in Taiyuan, China. It probably didn’t hurt that Sam won his first junior elite title. It probably also didn’t hurt that he was hatching a plan to move to America.

“It had been a dream of mine to go to the States since I was 8,” he says, recalling how the glossy BMX magazines had made an impression on him. “There was always a section on American racing, and it always seemed bigger and cooler to me. It looked to me like they were always racing in the Staples Center—even if it was really a rodeo arena in Reno.”

Sam had long fantasized about riding in the ABA Grand Nationals, held every Thanksgiving in Tulsa, so he mustered the courage to ask his parents. “I basically went home from China in June and asked my mom and dad, ‘If I save up enough money, can I go?’ And they said sure.” By the end of that summer of 2008, he was in California.

Meanwhile, Alise says, she asked her parents if Sam could live and train with them for a while.

Alise’s dad remembers it a little differently. “She told us this Australian boy wanted to come to the U.S. and race—and that he’s going to live in our house,” Mark recalls. “And the second day here, he’s walking around the house in his underwear rubbing baby oil on his legs.”

But Sam quickly became part of the family. He and Alise were both extremely competitive in races, but they otherwise had radically different approaches. Alise was often chilled out and socially inclined, a natural athlete with other interests, while Sam was an intense planner 24/7. “He always had a plan from the moment he woke up to the moment he went to bed,” says Lauren Reynolds, a fellow Aussie. Mark Post recalls that Sam walked around with a stopwatch that would beep at certain times, and he would stop wherever he was to stretch or whatever. He approached BMX as a science—breaking down all the components of the event and methodically training them individually—long before that strategy was on most people’s radar.

What had most certainly not been a love story was one now. In 2009, Alise headed to San Diego to attend college, and Sam came with her. They’ve been in California—and together—ever since. “I like to say that I’ve been with Alise since 2006,” Sam says. “And then she’s been with me since 2009.”

A BMX course is like life. It’s up and down. It’s chaotic. It can lift you into the air or slam you on your ass. Sam and Alise know this to be true. They have experienced all the highs and lows—both in life and in sport.

BMX is one of many sports that have a perpetual calendar but engage a truly massive audience only during the Olympic Games. Alise has won 10 national titles and two world championships. Sam, who won the first of his double-digit national titles at the age of 10, has earned five world championships, two as a junior and three as an adult. But ultimately, for better or for worse, their careers are often judged by their Olympic performances. In that regard, each has experienced triumph and disappointment.

Both riders made their Olympic debut in London. Both were young (Alise was 21, Sam 20) and both were tipped as medal contenders. And then their paths diverged.

On the men’s side, many observers had picked either Sam, the reigning world champion, or Latvia’s Māris Štrombergs, the defending Olympic champion, as the favorites to win gold. After surviving his opening round (“Honestly I was riding pretty rough”), he rode well in the semifinals, winning his bracket. And in the finals, he and Štrombergs had the duel that everyone expected. Štrombergs led from the start and Willoughby slotted into second in the first turn. The two of them separated from the field and held those positions. At the finish line, Štrombergs and the Colombian who finished third threw their hands in the air, but Sam’s reaction was harder to read.

“I was so in the moment, so my first reaction was a kind of disappointment—not throw-your-helmet mad, but just a big ugh,” he says. “But a little later I realized the magnitude of the result. I mean, they gave me a podium tracksuit and I went out there with my flag and could look out in the stands and see my family. It was a special moment, not at all like finishing second in any other race.”

For Alise, London really couldn’t have gone worse. She crashed in the second of three semifinal rounds, falling in a turn and landing on her backside. And in the last semifinal, she crashed even worse, awkwardly hitting the lip of a jump. After the other racers crossed the finish line, the cameras went back to Alise. She was being helped by two track attendants, injured and struggling and failing to get back on her feet to at least finish the heat. “Yeah, I crashed more than I stayed up in London,” she says. “It was a pretty poor effort.”

Alise says there’s a photo of them together near the finish line later that day. In it, Sam is smiling with a medal around his neck. She’s there, too, with red eyes, trying her best to smile. “I was sad but I was also so happy for Sam and what he was accomplishing,” she says, remembering how she mustered the spirit to help Sam enjoy the moment. “And it was his 21st birthday right after the Olympics and all of our families were together, and there was a lot that could still be celebrated.”

After London, they both went back to the grind. There were big wins and injuries and plans for both of them to do better in Rio. The usual sort of stuff that elite athletes face.

But then in April 2013, Alise got news that was not the usual sort of stuff. Her mother, Cheryl, had been seeking treatment for back pain and doctors discovered that she had stage IV melanoma.

Sadly, Cheryl’s cancer moved quickly. She spent much of her final year doing the things that meant the most to her. She still went out to Pineview every week all summer, even after she had to go there in a wheelchair. She remained Alise’s number one supporter, absorbed in her daughter’s talent and success. “I mean there were moments where she was down and scared and anxious,” says Alise, “but she was super positive and happy right to the end.”

Alise took as much time as possible to be out in Minnesota as her mother’s health declined. “None of the treatments were really working; things were just masking symptoms but nothing was regressing the situation, so I definitely took time to go back there,” she says. Through all the pain and distraction, Alise buried herself in her training and competition. “My mom was my biggest fan and wanted nothing more than to watch me race all the time. I didn’t race very well at the end of 2013, but I did race.”

She remembers the last race she did before her mother died. It was a minor competition, one that didn’t matter in the grand scheme of things. She certainly wasn’t in optimal shape, physically or mentally. “But I somehow won both days of that race,” she says, her eyes suddenly moist. “That was some sheer greater power working with me, because I shouldn’t have won. But my mom watched them online and called to say she was super proud and happy.”

Cheryl died the following Tuesday. Her wake was held on Alise’s 23rd birthday.

After that, Alise threw herself into her training. “I obviously didn’t cope with it or deal with it very well,” she says. “I guess I just went on with what I’d normally be doing.” But she wasn’t really in the right headspace. And at her first World Cup race that year, she broke her leg. She was forced to sit back and reset. She also started seeing a sports psychologist. Things started to fall into place. Meanwhile, Sam was winning the World Championship.

They went into the Rio Games realistically full of optimism.

Sam entered the Games on a tear and rode beautifully through the opening rounds. He won all six of his quarterfinal and semifinal heats with fast times. But in the finals he was flat from the start and wound up finishing sixth, out of the medals. “Man, that was a disappointment,” Sam says.

But Rio was like London turned upside down: It was Alise’s turn for success.

In the finals, defending Olympic champion Mariana Pajón of Colombia got to the first corner first and never relinquished that position. But Alise had a couple of bursts of explosive speed and challenged Pajón before finishing second. Much like it had been in London, the champion and third-place finisher, from Venezuela, celebrated as they crossed the line, while Alise slumped down in her seat and tilted her head toward the sky.

“It’s hard to explain how competitive she and Sam are,” says Reynolds, who’s trained and raced with them both for almost two decades now. “They treat each race like a war they need to win.”

But now, like Sam, Alise understands the lasting meaning of that silver medal. “It was an incredible experience,” she says. “It felt like my mom was there, sitting in a front-row seat.”

He had expected to get the wind knocked out of him. There had been nothing remarkable about the crash—a minor flub on the low-key rhythm section at the Chula Vista track—but now Sam was lying on his back. He couldn’t feel his legs or his chest. He really couldn’t feel anything except a rising sense of panic.

It was a Saturday, only 22 days after his disappointment in Rio. Even now, it’s painful to recount how and why he was even at the track that day. He’d originally planned to join Alise at a charity event in Minnesota but changed his plans at the last minute.

“I didn’t really deal with that disappointment,” he admits, invoking another parallel with Alise’s experience. He’d been busy celebrating with Alise, and then going to Australia to face sponsors and fans, and after that he just threw himself back at training. “My mentality was, ‘I’m going to win my next race to fix Rio.’”

But the next race didn’t go well either. And an ACL tear he’d suffered in the runup to Rio wasn’t getting better on its own. These were all things that hovered in the back of Sam’s mind when he decided not to join Alise and instead fly back to San Diego. “I was like, ‘I’m just going to bury my head in the sand and train, train, train,’” he says. “And win my next race. Just a bull-in-the-gate mentality.”

It’s funny the things you remember from a pivotal day in your life. Sam remembers taking his dog, Mila, for a walk down to Subway and buying a sandwich. He remembers texting with his friend, countryman and fellow Olympian Khalen Young, who urged him to get his knee fixed, take a break…to reset. But Sam went to the track anyway. It was an anchor of his existence, and besides, he planned to just mess around and ride rather than train.

“I was just doing a routine warmup,” Sam says. The rhythm section, a common BMX track feature, is a mellow stretch where small bumps are tightly spaced; Sam was rolling those undulations on his back wheel. “I always manual the rhythm section to warm up. I just overcorrected, and I remember being in the air.”

BMXers call this “looping out,” a wheelie gone wrong, where a rider pulls the bike too far and falls over backward. For a seasoned, highly skilled pro like Sam, it was at once an oddity and not terribly dangerous. But in that moment, a perfect storm occurred.

“I vividly remember thinking that I was going to be winded,” he recalls. “And by the time I hit the ground I realized I wasn’t winded. And that didn’t make sense. But I’d actually gone upside down and come down on the top of my head. I couldn’t feel my legs and just felt like my legs were way off in the distance. And then I just started screaming, ‘I can’t feel my legs, I can’t feel my legs!’”

Sam didn’t know it then, as he was lying on the dirt in Chula Vista with other riders and onlookers hovering over him, but he had landed on his head and fractured his C6 and C7 vertebrae, dangerously compressing his spinal cord. Another rider’s father was an EMT, and he stabilized Sam’s body and began doing a head-to-toe check. “He started running up my legs, and he got his hands at my chest here, and I could see his hand right there, but it felt like his hand was a foot off my chest,” he says. “I felt like my whole body was in a wetsuit full of water.”

Minutes later, before the Life Flight helicopter lifted off to take Sam to the hospital, Alise got the call. She’d been on her way to Target Field to throw out the first pitch at a Twins game, but instead she raced to the airport to catch the first plane to San Diego.

In the emergency procedure that followed, surgeons replaced Sam’s C6 vertebra with a titanium cage and fused his C5 and C7 vertebrae with a plate and screws. It was enough to decompress his spine, but even a couple of weeks after the surgery, he had no movement below his chest.

The recovery that followed was a long, grinding process marked by intense work, small victories, and existential agony. Sam spent three months at the prestigious Craig Hospital outside Denver. Once again he buried himself in the task at hand, his physical recovery. He did rehab twice a day and obsessed over the idea of walking again, rather than wrestle with the emotional consequences of his injury.

“I was at a low point, pretty depressed, and the only thing that mattered to me was rehab,” he says. “I wasn’t getting better and I didn’t like who I was, and I didn’t want to see what I was at that point.” When he was released from Craig in late December, doctors there told him he would need a high level of assistance for the rest of his life, Sam says.

“I went from being an alpha male, very self-confident and successful at what I did,” he says. “That was my identity. But now I was at a point where I needed help getting into a car, I needed help getting into a restaurant, I needed help picking up a fork at one point. It was tough, for sure.”

Even though Sam was in a pit of self-loathing and even tried to push Alise away at times, Alise didn’t have any second thoughts about what to do. “I definitely took on the role of backbone for him and approached it like a process-driven athlete,” she says. “I knew him obviously well enough to know that he would feel like this burden, especially in the initial stages.”

Alise’s racing fell by the wayside. Even though she’d just won silver in Rio to cap a great year of competition, she was too busy caring for Sam, or being present for his treatment and recovery, or simply worrying about him. “Much as BMX left Sam’s mind, it left my mind too,” she says. “I had thoughts: Why am I riding bikes? What am I doing in this sport? Does this matter?”

In late November, about a month before Sam’s release from Craig, Alise decided to race the Grand Nationals in Tulsa—Sam’s favorite event since adolescence. On her travel day she woke up in a bed at the hospital, where she’d been staying with Sam. She flew to Tulsa with her dad for support, a role Sam had always dependably played for her. Alise won the pro women’s competition. But as it turned out, this event marked the end of her longtime relationship with her bike sponsor, Redline, the same company that had also sponsored Sam for years. It really pushed Alise to the edge. “I’d just had the most successful year of my racing career, but then my husband had a career-ending injury and we lost our eight- or nine-year sponsor, all in the span of weeks. It made me question, ‘Why am I doing this?’”

In January 2017, soon after Sam and Alise arrived back in Chula Vista, Sam’s mother flew in from Australia, along with his brother and sister-in-law, to help him transition and give Alise a little space to train and race. But it wasn’t exactly working out. Her head was full of worries. “I asked myself if it’s okay if I leave him, and would he be okay? And when he wasn’t comfortable in his own skin, how am I going to be comfortable with him?” she recalls. “So I think those first few races were really hard. There was this sense of guilt, like, ‘This is what took so much from you, and should I really be out here rubbing it in your face?’”

Not surprisingly, Alise crashed in nearly every event she raced at. Although she escaped serious injury, one of those crashes, in Florida, looked pretty bad. “I was there at those races, but I wasn’t there,” she says. “When you get in that gate you have to tune that stuff out for those two and a half seconds, you need to be in a clear headspace. And I was having trouble doing that.”

Sam, who obviously was struggling with his own demons, saw Alise struggling too. “I remember her coming home from that race in Florida and she was like, ‘None of this matters.’ But I remember thinking: It does matter. It was important to me that Alise had a purpose beyond being my caregiver. Like that was my biggest fear: ‘I don’t want you to stop what you’re good at and stop chasing your purpose and your goals because of what I’m going through.’”

The first few months of 2017 were pretty rough. But an unexpected turning point came in late March. Sam is a longtime NASCAR fan, and a friend hooked them up with VIP tickets in Fontana that included meet-and-greets with top drivers like Jimmie Johnson and Kasey Kahne. They were also planning to meet Bootie Barker, who at the time was crew chief of the #13 car. The friend told Sam that they’d known each other for 30 years and that Barker was in a wheelchair. This revelation set off alarm bells in Sam’s head. “At that point I didn’t want to meet anyone in a wheelchair,” he says. “I only wanted to talk to people who walked again. To me that was the only story I wanted to live.”

Barker was loud, direct, friendly, and most certainly in charge of a multimillion-dollar racing operation. He rolled around the team’s hauler and showed Sam a bunch of new engine data. Then Bootie started asking questions that would change the arc of Sam’s life.

“How long you been hurt, brother?” Barker asked.

So Sam told him seven months. “You look great,” Barker replied. “What are you going to do now?”

Sam says he really had no clue how to answer that question. His brother, Matt, who was there too, stepped in to mention that Sam was doing tons of rehab with a goal to walk at his wedding. “Cool, brother,” Barker replied. “Then what?”

Matt could sense Sam’s confusion, so he asked Bootie at what point he stopped doing rehab. “Rehab?” Barker answered. “I didn’t do no rehab. They said at the hospital I could dress myself after six weeks, so I got the hell out of there and went and got my engineering degree and got on with it.”

Sam is a bit misty now. “Bootie looked at me and said, ‘You’ve got to get on with it, brother.’ He looked at my brother and said, ‘Him and me are the same as you, we just have to drag ourselves around a little more.”

Sam and Matt asked Barker about the complications of traveling—like whether he always got an accessible room—and he just laughed. “I don’t need a special room. If the bed is higher then I just push a little harder. And I just get my ass in the bathtub.”

The message was received. That night, Matt helped Sam get his ass in the bathtub.

Alise says Sam’s perspective shifted almost overnight after that trip. “The attitude shift was night and day,” she says. He still felt obsessed with the idea of walking at his wedding, but he understood that there were bigger fish to fry.

Just as Bootie had urged, Sam understood that it was time to get on with his life. So that’s what he did.

Now Tokyo is looming. Sam and Alise are discussing the run-up to her third Games as they sit on the patio of a Starbucks in Chula Vista. Alise is in artfully ripped jeans and Sam’s biceps are challenging the sleeves of his Troy Lee T-shirt. Mila, their pit mix, sits under the table in quiet repose unless another dog or someone wearing a brimmed hat enters her zone.

For roughly four years now, Sam has served as Alise’s coach. Their full collaboration began at a time when they were both struggling to find their way within the sport they’d each dedicated most of their life to, at a time where they’d both faced losses and struggles. They began a new routine: Sam did his therapy in the morning with Alise’s help, and Alise attacked her training under Sam’s guidance.

Sam says he was excited to get back to the track. “I never had any animosity toward the sport,” he says. “I feel the same as I did before. I have the same responsibility and passion for going to the track.” Meanwhile, Alise felt like Sam’s about-face after meeting Bootie gave her the freedom to pursue her passion without guilt—and with an expert guiding hand.

The first big test of their collaboration came just a few months later. The 2017 UCI BMX World Championships were held that July. Every world championship is important, of course, but this one was on home soil, in Rock Hill, South Carolina. And Alise had never won a rainbow jersey at worlds. But that’s exactly what she did. “It was huge,” Sam says with a smile on his face.

Their routine, especially at first, was not exactly routine. They had not yet really traveled as a couple after Sam’s injury, and now they were traveling to world-class sporting events in far-flung countries. Their second trip together was to Azerbaijan. “To Alise’s credit, she’s dealt with stuff the night before races that no one knows about,” Sam says. One time he spilled very hot coffee on his legs and got third-degree burns on his thighs. (Because of his injuries, he can’t feel pain in his lower extremities.) Alise spent a couple of late-night hours searching for a 24-hour pharmacy and treating his burns.

“These are things people don’t normally think about when they’re racing,” says Alise. “We’ve learned that we deal with chaos.”

But as Alise and Sam talk about navigating these challenges, it’s obvious that there’s a positive to counterbalance every potential negative, a gift to complement each stumbling block. You can see it in the way they exchange tender smiles as they tell stories of the melodrama. For people who are relatively young—Alise is 30 and Sam will hit that hallmark a week after Tokyo—they’ve been through a lot together and come out stronger.

They each try to put this into words. “It’s become my purpose in life—to provide Alise with the most support and direction in the best way I possibly can,” Sam says. “I would try to turn over every leaf to try to give her as much support as I can, because I probably will feel forever in debt to her for her support, the way she was by my side for what was the worst period of my life. Now I just have so much motivation. It feels really easy to get up every day.”

“It truly feels unconditional,” she says, her eyes watering again. Alise and Sam are talking about existential matters in practical terms, as you might expect from elite athletes talking to a relative stranger, but the emotions on the table are as clear as day. “Sometimes things can turn conditional, right? And I think that’s part of the strength of the relationship, on both the professional and personal sides. I know he’s there 120 percent, with no ulterior motive, no ill intention, there’s literally nothing he wants more than me to do exactly what I want. And I can be 100 percent me, say whatever the hell I want to say, and he’s going to listen to me.”

Sam’s approach to coaching is much like his approach to riding had been. It is data-driven, process-driven, science-driven. “Physiology is physiology,” he says. There is intense work in the gym, lots of uphill intervals, specific focus on every component of a BMX race. Right now, six weeks before the Olympics begin, they are working on lengthening Alise’s accelerations. Everything is intention.

“Sam is just really good at tracking and remembering the data,” Alise says. “And he can relate it to me in simple terms so when I get to a race day I know what’s expected of me.”

They both hope their partnership will bear fruit in Tokyo. There, Alise will again face off with Colombia’s Mariana Pajón, who won gold in Rio and London. The two of them first raced when they were in middle school—two decades spent alongside each other in that starting gate. “There’s a mutual respect. We ride for the same brand and have traded wins for a long time,” says Alise, referring to her current bike sponsor, GW Bike USA. “But sure, a win in Tokyo would be sweet. In recent years I’ve been able to get better just by getting more out of myself on important race days.”

Her coach agrees. “I think we’re embracing the things that she’s good at,” Sam says. “As an athlete, I think she’s probably the best in the sport. Helping her realize and embrace those strengths is a focus, maybe in the past she’s been more focused on her weaknesses. She has more strengths than weaknesses.”

Sam and Alise got married on New Year’s Eve in 2017, exactly one year after Sam got home from Craig. They’d originally picked a wedding date the preceding April, but life happened. They rented a loft space in San Diego—a blank space that Alise could pour some creativity into. Family and friends from Australia and Minnesota and elsewhere who hadn’t seen the couple throughout the whole ordeal flew to San Diego for a full week of holiday celebrations. “It was like the best week of our lives,” Sam says.

Sam was still in the phase of obsessing about walking. After more than a year of hard work and rehab, he was able to walk down the aisle with the aid of braces that kept his knees locked. And during the ceremony and their first dance, he didn’t use a walker. “We practiced a lot in the backyard,” Sam says. “I got pretty good at it, but I was not that good that day. In some of the photos we’re standing there smiling, but if you look closely Alise has veins bulging out her arms.”

“I got my workout in that day,” Alise laughs. ”We had a good friend who married us. And I was like, ‘Okay, hurry this up.’”

But the beauty of the moment was no joke. They took vows like so many couples do—about having and holding, for better or for worse, in sickness and in health—phrases that can feel like empty platitudes. The truth is, most young couples haven’t yet wrestled with the substance of these promises, and as time goes on, many marriages buckle under their weight. Even in marriages that thrive, so often both individuals can only hope or speculate how they’d fare if things went south. But already, Sam and Alise on their wedding day could look each other in the eye with complete confidence that they’d already lived their vows.

Everyone at the wedding formed a circle around Sam and Alise as they shared their first dance, to Ed Sheeran’s “Perfect,” a song that celebrates a couple who fell in love as kids. Sam was on his feet, willing himself against the odds to move with the music. Alise was holding him tight while holding him up. It’s simply not possible to dance more together than that.