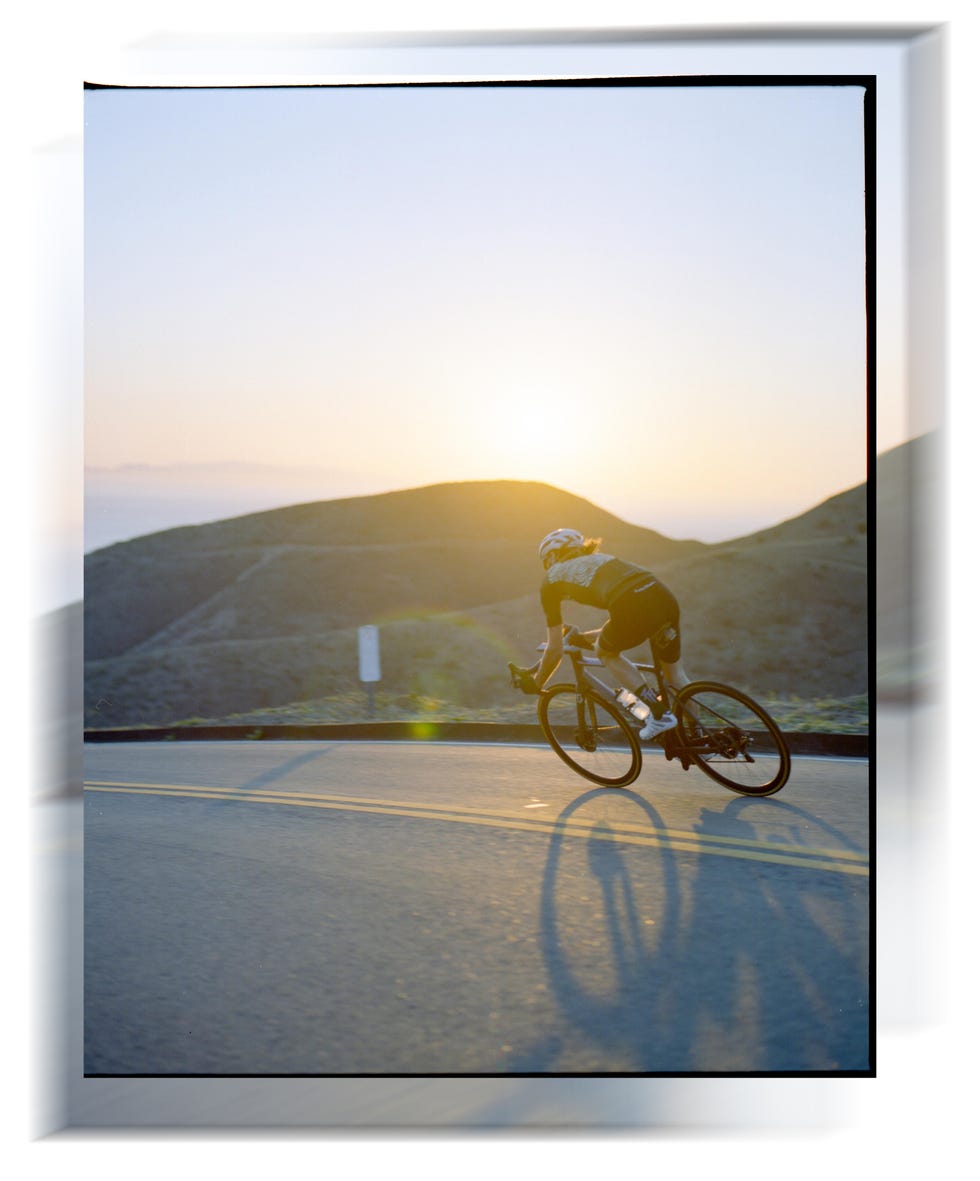

It’s the flagrant angle of the bike that catches me off guard. The rider flings his machine into a corner, his body pitched unnaturally to one side, as if the rules of physics are merely things to be fucked with, and that fear—even the faintest traces of it—is somewhere behind him, far up the canyon he’s currently barreling down, dropped and left gasping for air in the gutter.

Now the rider drifts from the white line along the right side of the road to the double yellow and then back again as he skims another corner. No sooner has he navigated these two turns and he’s melting into a super tuck, all his movements—his entire being—blessed with a preternatural grace, even at 56 miles an hour with the western fringe of the Continental 48 plunging hundreds of feet to the Pacific far below.

There are other features that compel me to watch the 25-second Instagram clip over and over again as I sit safely on my couch—some sensual, most visceral. The wind whirring past the cameraman’s mic. The cicada zing of the rider’s freewheel. The blue blur of the ocean that blends into the horizon in the hazy summer light; the early morning sun, already white and washed out as it rises from behind the Santa Monica mountains; the sepia-toned scrub grass speeding by on either side of the fish-eye frame, allowing the viewer to burrow deeper and deeper into the singular world of the rider known as Safa Brian to his more than 200,000 followers across Instagram and YouTube.

“Jesus Christ, that’s maniac shit,” writes the first friend I DM the video to, a downhill mountain biker who never gushes over anything remotely related to road cycling. My wife shares a similar response, turning away within seconds of my leaning across the couch to show her the clip. “No, no, no,” she says, hand darting to mouth, eyes squished shut so as not to witness the crash she’s sure will come.

There is no crash. Only a caption that might as well be a mic drop: “Deer Creek in under 3 minutes. It’s a thing…now.”

→ Sign up for Bicycling All Access and get more great reads like this one.

For the uninitiated, Deer Creek is a two-mile twist of California road that veins the hills north of Malibu, dropping riders down an 11 percent pitch that, like most of the canyon roads out there, T-bones into the one-lane traffic along the northbound side of the Pacific Coast Highway. As far as L.A. canyons go, it isn’t one of the most technical, and yet the way Safa Brian rides it leaves little room for error. The stakes are high, the threat of a crash sometimes looming only a tire’s length or two to one side of the road. This might be the video’s defining feature, but it is not the sole appeal. There’s an artistry on display beyond the skill required to ride at such high speed. You see it in the soft light, the sound, the vibe, the flow, all of it belonging to a vision that feels as dialed as the dude’s descending. In many of Brian’s videos, a soul-restoring sense of beauty mingles with the specter of serious injury or, in the most white-knuckle of them, maybe even death. This tension charges each clip with an immediacy not otherwise found in a sport whose romance has long been defined by the slow-burn sufferfests spent riding up mountains, not down them.

WATCH: SAFA BRIAN DESCENDS DEER CREEK

“I get called crazy all the time. Mostly in a friendly way. But I think it also kind of diminishes what I do,” Safa Brian tells me over Zoom in early March from his apartment in West Los Angeles. His real name is Brian Wagner, and he shares the place with his wife, Ninna, and their cat, Gatito, a stray the couple rescued while living in Mexico City.

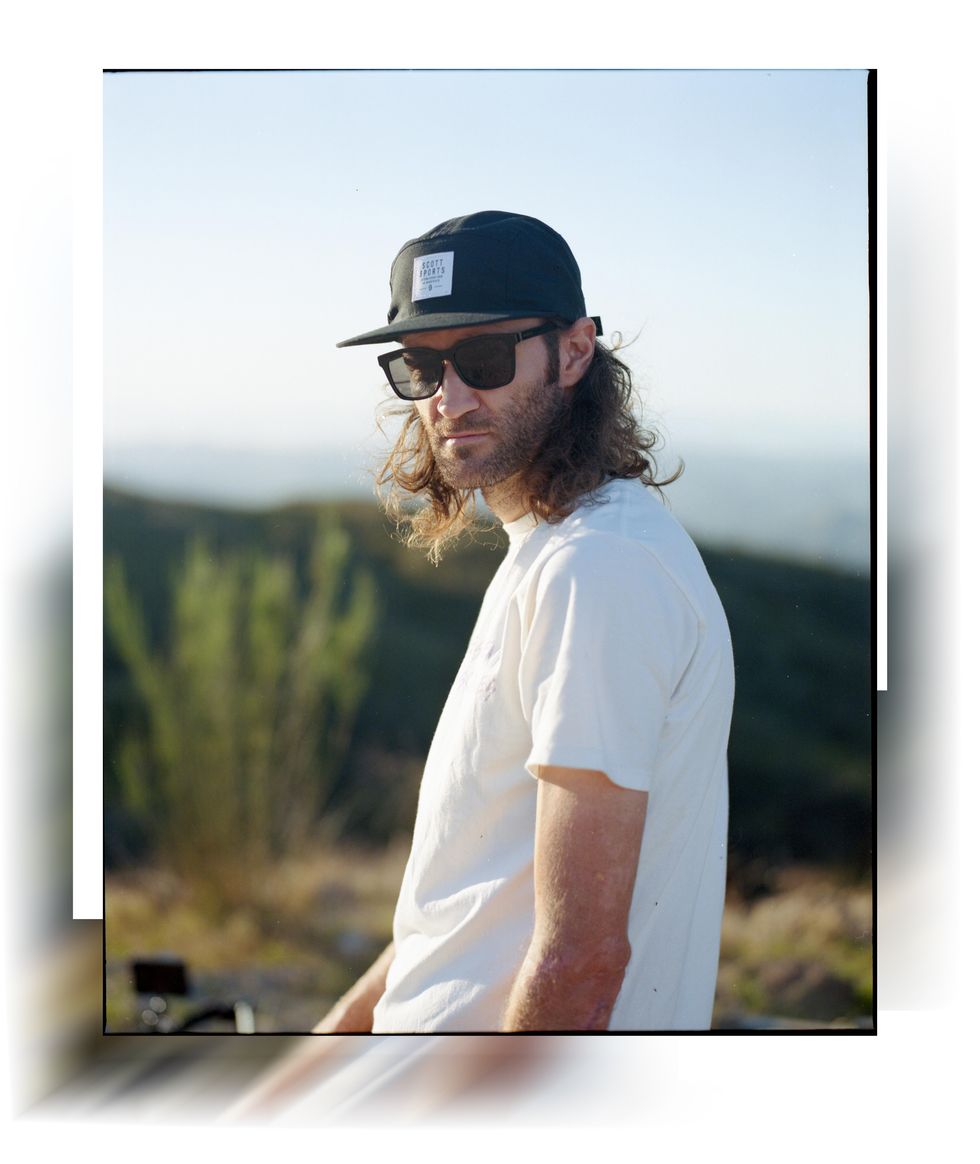

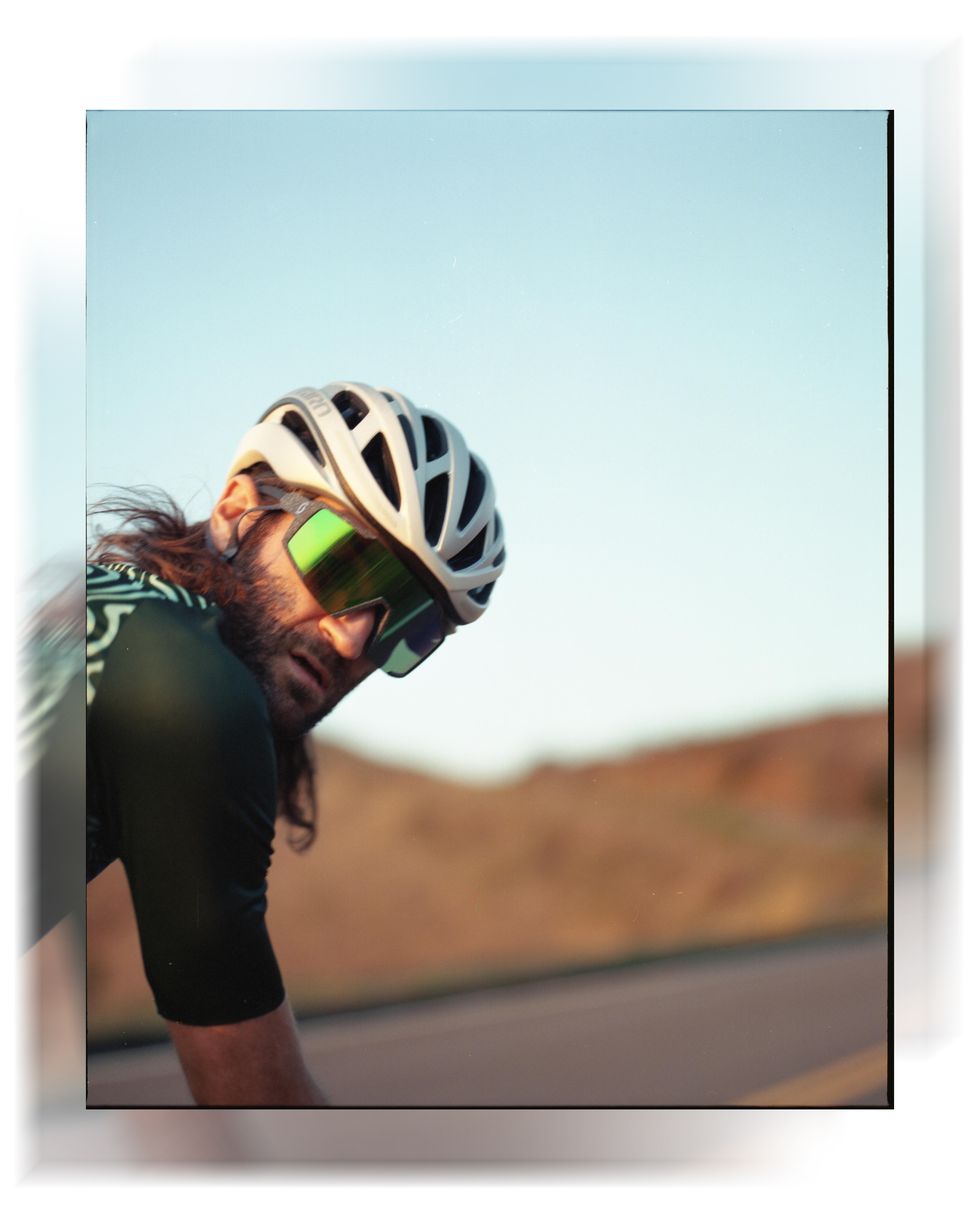

All I see today, however, are bikes hanging on a wall, most notably his Scott Addict RC Pro, a brand he’s ridden for years and now rides exclusively, per his sponsorship agreement. He speaks to me via the computer that serves as the editing bay for his popular Descent Disciples YouTube series. Typified by speed, Descent Disciples is an 11-volume body of work that’s seen the soft-spoken 35-year old South African (hence the Safa moniker) set KOMs down some of Greater L.A.’s most coveted canyons. Even without the helmet and sunglasses he wears in the videos, his scruff and long hair make him instantly recognizable. Brian might have the physique of a high-caliber cyclist, all sinewy limbs spiderwebbed by the type of thick-rooted vascularity attained through years of endurance sports, but his aura is more punk rock than World Tour.

Brian speaks laconically, carefully considering my questions before answering. He’s eager to talk about what he does—the risks, the skill, and how the latter enables the former. But I also sense a reticence as his blue-gray eyes dart shyly to the right, averting the camera. For the past year he’s devoted himself entirely to his films, getting the colors and the light and the sound just right, with an intentionality not often seen in the world of cycling cinema. Now this man, someone described as intensely private by his friends and family, is just handing his story over to some New York City journalist he’s never spoken to before.

Journalists, we both agree, can sometimes be misleading. Especially journalists writing about those sports deemed, for lack of a better word, “extreme.” In such cases, we can default to facile summations, ones that praise daredevilism over skill, as if, in Brian’s case, the only prerequisite to descend at such dizzying speeds is a lack of brain cells.

This of course isn’t the case. In conversation, Brian exudes an intelligence that borders on the philosophical, and he seems to employ this same deep-thinking mentality when riding. Descriptors abound anytime Brian straddles a bike. The guy rips down a road the way Alex Honnold free-climbs up a mountain: quickly, obsessively, death-defyingly, and, above all, mesmerizingly. Brian shot the first installment of Descent Disciples two years ago, and when the pandemic hit he decided to venture further into the unknown by ditching his messenger job to pursue filmmaking full-time. Though he had no formal experience as a filmmaker, his work immediately struck a chord. Video views racked up, comments poured in, fans gushed, and his audience—stuck indoors due to COVID and perhaps looking for the type of enrapturing content that could free them from their domestic confines—swelled. But with this sudden acclaim came criticism, too.

Unlike Honnold, who plies his craft on the barren rock walls of inaccessible mountains, Brian often shoots his segments on public roads, sharing the asphalt with motorists and other cyclists, and this opens him up to scrutiny. Yes, his descending is fast and, at times, perhaps dangerous, especially in the eyes of the less talented. But these risks are primarily assumed by Brian and, sometimes, his small crew. There’s also the fact that his style of riding has the potential to contribute to the negative stereotypes cyclists face in the eyes of drivers who don’t like us, or, in the event of a collision, want to offload blame by claiming we flout the rules of the road.

To Brian, the dilemma is more “damned if you do, damned if you don’t.”

“I know from riding as a messenger for so long, that you can sit in the bike lane, never break the speed limit, stop at every stop sign, and you’re still going to get someone spitting on you, throwing beer bottles at you, shouting ‘fuck you’ because you’re riding a bicycle,” Brian says and shakes his head. “Just because you’re riding a bicycle you’re hated. That’s the fact. You can’t convince me otherwise.”

Whatever the case, Brian’s films can sometimes touch a nerve. Scroll through comments on YouTube, Instagram, or various subreddits, and amid all the praise—calling his riding “epic” and “amazing” and “mind-blowing”—you’ll find detractors who label Brian “moronic,” “lunatic,” “sketchy AF,” and a “public menace” who is “the main reason cyclists have a bad rep” and who might “very likely die doing what he does.”

Brian’s heard all the hypotheticals. How his videos might inspire riders who are less skilled to attempt similar stunts. How his descent speeds, or the fact that he sometimes disregards yellow lines or stop signs, give cyclists a bad name, or worse, tarnishes them as risk takers whose disregard for their own lives means they also deserve to be disregarded by drivers. One critic, Brian tells me with a bemused laugh, even suggested a scenario in which he could crash through the windshield of an oncoming car and kill half the family inside.

Some of these gripes Brian accepts, understanding that they come with the territory. Others seem outlandish, even death-obsessed, which he thinks says more about his critics than about him. It’s one reason he was apprehensive to sit down for this interview: How would he be portrayed? How would what he does be scrutinized? What would online commenters squabble over this time?

Though Brian has far more fans than detractors, some of the criticism is particularly hard to take, especially from the self-appointed cycling gatekeepers who tend to be the most vocal critics. In the subset of road cycling where coffee shops and matching kits and bespoke training plans prevail, tradition is paramount, with riders new and old expected to adhere to a set of unspoken rules that can feel as precise and robotic as a paceline. Veer outside those narrow lanes, say in a T-shirt and jeans, long hair flowing, bike drifting from one side of the road to the other while cutting a corner’s apex at speeds approaching 50 mph, and you can expect to catch some heat.

“It’s annoying because I see so many other sports where people are free to do what they want and to show their talent and skills,” Brian says, his voice measured—and sometimes so low it’s a mumble—but the irritation palpable. He rattles off edgy brands embraced by the mainstream (X Games, Red Bull), pointing out that their content doesn’t come with disclaimers. “But as soon as you do something on skinny tires, the audience is a totally different audience with a different mindset and this constant need to criticize.”

Racing, in his eyes, is far more dangerous. Just go to your average crit and count the crashes, tally up the broken bones. Okay, fine, so today Brian’s right arm sits in a sling too, his collarbone fractured when his front wheel washed out down the dirt of Sullivan Canyon. But it’s the first bone he’s broken on a bike in over 10 years. Can most pros claim the same?

And then there’s the irony of being labeled by some as the guy giving cycling a bad name. He points out the World Tour, with its history of racism and sexism, not to mention the deeply ingrained culture of doping and cheating. He mentions the fact that some of today’s biggest teams are backed by countries with human rights violations. Brian shakes his head. “But I’m the guy who makes cycling look bad? I think there is a lot more going on that [my critics] could direct their energy at.”

While Descent Disciples became Brian’s way into mainstream road cycling, the type of content he could afford to produce on his own, as well as a way to showcase his left-field ideas, it is not his goal to continue being just the guy blazing down Strava segments. Already he’s expanded his purview. There’s Gravel Gods, showcasing the dirt canyons of L.A., and he’s fresh off the premiere of Pray for Speed, a 13-minute road-trip movie shot in SoCal’s hinterlands.

WATCH: PRAY FOR SPEED

Brian’s fans are there for the wide array of content in his videos—from soulful sunset cruises high up in the hills above the Pacific to whipping-around-corners action. Many reach out to tell him how his work has inspired them to pick up road cycling, a sport they previously considered uncool or too exclusive. When Brian rides with pros like Movistar’s Matteo Jorgenson (who says Safa’s content reminds him of the skating videos he grew up on), he approaches the shoot the same way he does when he films with his friends: There’s no agenda. He doesn’t care about crushing descents or even going hard; he just wants to film them doing their thing, whatever it is on that particular day.

“The more we see people riding how they want to ride,” he says, “the more we’ll see a broader audience attach themselves to road cycling.”

Brands, however, have been less keen to embrace this idea. Although Scott is on board, he’s had a hard time articulating his other ideas—ideas that do not fit within the traditional rubrics of road cycling—to more sponsors. Brian hints at this vision to me, suggesting road trips, landscapes, vibes, all of them belonging to this knot of nebulous ideas that would take road cycling beyond its racing roots, if only the industry would trust his instincts and understand that he seeks inspiration elsewhere. He admits that he watches more surfing videos than cycling videos these days, and he feels that some similarity exists between the two sports “in the feelings you get.” Sure, it’s more drawn-out to fang it down a descent on two wheels than to get barreled inside a fast-breaking wave, but both have that big burst of adrenaline followed by the quiet aftermath, in which the athlete is left to process what they’ve done, and maybe to wonder why they’ve done it. He shrugs, a fatalistic tell that suggests that Brian Wagner is accustomed to being misunderstood.

“I could show [these brands] a surf film and tell them I am trying to do something similar,” he says. “But people just don’t get it until you’ve done it with bikes.”

Since his childhood in South Africa, Brian has always related best to the world by bike. His mother, Sue, gives me the backstory via email, from her home in Namibia.

“Brian is a private, deep-thinking person,” she writes. “One who cares about those he loves but who does not easily express his emotions.”

The Wagners—Brian has an older and a younger sister—spent much of their youth scooting around South Africa and neighboring Eswatini, then more commonly known as Swaziland. Sometimes this meant living in semi-urban areas; other times they made their home off the dirt roads of the African countryside.

Sue says her son did not always exhibit a natural ability when it came to sports, but he worked hard. “I remember him spending hours riding his mountain bike, trying new things, trying to perfect various skills like how slowly could he ride, how high could he bunny hop, how fast could he complete a certain route,” she says. Brian’s obsessive practicing jibed well with her parenting philosophy. If the sun was shining, Sue told her three children they’d best be playing outside. Together with his sisters, Brian built obstacle courses over 44-gallon drums, devised treasure hunts, concocted makeshift waterslides from tarpaulins and dish soap. He preoccupied himself with ping-pong, often practicing with the opposite side of the table heaved upright as a backboard, and by high school he was competing regularly in track, cross-country, and mountain biking. Academics fell off the radar in the latter half of his teenage years—a pity, Sue concedes, considering the “good brain” her boy’s got—and after graduation Brian left South Africa for Australia in 2002. The plan was to stay for a gap year before the drudgery of university took over. But then a chance meeting with a bike messenger got in the way.

“I was in an elevator in Sydney and this guy got in,” Brian says, recounting an interaction he had after weeks sleeping in hostels and living like a hermit, a shy country kid whose accent and tendency to murmur made him hard to understand. “He was wearing a helmet and a backpack. I don’t normally speak to strangers, but I just started chatting to him. He told me he was a bike messenger. That was the first time I’d ever heard of it.” Here Brian looks away from the camera, sheepish and red faced, and allows the rare smile to creep crookedly across his face. “I was like, ‘You just ride around delivering stuff?’ Then I asked him, ‘How do you get that job?’”

Two weeks later, his mother had shipped him his old mountain bike and he had a new occupation. Sue was concerned, of course. She thought of the injuries and the financial hurdles her son would surely face. But she’d also taught her kids that passion was important in life.

Brian worked as a bike messenger for the next 16 years, sometimes delivering as many as 90 packages in a day. It would take him all over the world, from Sydney to Melbourne to Perth, and then on to London and Glasgow before he crossed the Atlantic for New York and later headed down to Mexico City. He liked the challenge of mastering the routes of each new locale, as well as the camaraderie and competition among the messengers.

“To me it was the coolest job ever,” Brian says, again breaking into that rare smile. “There were so many interesting, talented people. It was almost like a bunch of artists who decided that this was the best way to make a living, and they all loved bikes.”

The job and accompanying lifestyle consumed him. Brian lived with messengers. Partied with messengers. Raced with messengers. He frequently attended the annual Cycle Messenger World Championships, racing in places as far-flung as Chicago and Guatemala and Switzerland, and sometimes got disqualified when his appetite for speed meant he missed a checkpoint or had his manifest stamped incorrectly. He fared better in the alley cat races at Messenger Worlds, which prioritize speed and skill over paperwork, twice reaching the podium (a win and a second place).

Beyond the races, however, it was the community he craved. Call it a family of cyclists, and it’s a feeling Brian’s been after ever since.

“You see his sticker everywhere,” says Rafael DaSilva, who speaks to me a few days later at Brian’s behest from his apartment in Venice Beach. Rafael is talking about the Pray for Speed logo. Dreamed up by Brian and designed by the Mexico City street artist Muta, it features a hooded skeleton with hands pressed in prayer, and it can be found across all Pray for Speed merchandise, from stickers to T-shirts to kit collabs. Alongside income streams that include sponsorship money and revenue generated via YouTube’s Partner Program, merch sales have helped Brian cobble together this unconventional life as social media’s preeminent road bike descender. Most of Safa Brian’s followers will recognize the Pray for Speed skeleton from the center of his V-shaped Syncros handlebars in any POV video. But to local riders, it’s most commonly spotted atop the hills of west L.A. and Malibu, where it’s become as ubiquitous as a graffitist’s tag. “All you have to do is look behind the street signs,” Rafael says. “It’s very widely recognized.”

Rafael sees the sticker as an embodiment of the community his friend has created. When the two go riding together, they get friendly shoutouts from disparate packs of cyclists—roadies, BMXers, fixed-gear riders, you name it. Sometimes, Rafael even gets recognized on his own—“Hey, are you the guy from...what’s his name? Safa?”

Brian and Rafael connected on Strava nearly three years ago and met in person soon after, during a group ride out of Santa Monica. Brazilian by birth, Rafael grew up worshiping the late Formula 1 legend Ayrton Senna, and this love of motorsports led him to motorcycle racing in this country. He found success on the national level, until he crashed at a race in Wisconsin in 2017 and blew his right knee out. A doctor suggested cycling as an active form of rehab, and Rafael was quickly hooked, especially with the descents, where his motorcycle pedigree made him a natural. As they say, game recognizes game, and it didn’t take long for Rafael to spot a kindred spirit in Brian, even if their styles differed.

“I’m more of a sweeping rider using all the road,” Rafael says. Like Brian, Rafael is nursing an injury, a broken femur he suffered after crashing in 40 mph crosswinds. In Brian, he sees an altogether different type of descender. “Safa, coming from a messenger background, uses more sharp, quick movements.”

The two teamed up in 2019 for the first installment of Descent Disciples. The initial video contains all the trademarks of the series: the light, the speed, the smooth cornering, the California coastline. Except it’s Rafael descending with Brian filming. That format soon changed, and not long after that—understanding that his friend would require a professional cameraman—Rafael introduced Brian to an old motorcycle pal, who goes by the social media alias Bucky Sacrilege.

“I saw him as this punk rock, off-the-beaten-path kind of kid,” Bucky tells me from his bedroom, adding that he’s a social butterfly compared to Brian, the introvert. Bucky has a mustache and wears a skullcap out of which sprouts shoulder-length brown hair, and—whether injuries are mere coincidence or more commonplace among this trio than they’d like to admit—his right arm sits in a sling. The latter is a result of a wheelie gone wrong on his motorcycle, which landed him in the hospital with nerve damage and a chest tube. Bucky’s first encounter with Brian was far more sedate. After swinging by Brian’s apartment, the two rode around Westwood—Brian on his bike, Bucky on a Yamaha R3, which he decided would be best for sound quality due to its lower displacement. The two quickly established trust, and soon they were filming their first video.

“Gosh, it’s kind of hard remembering which one it was,” Bucky says, cocking his head to one side in thought. “I got a TBI in my motorcycle accident, so my short-term isn’t great.”

What Bucky does remember is Brian’s painstaking attention to detail and safety. Brian often stays up late studying wind patterns online; then on the day of the shoot, the two perform test runs down whatever descent they’ve selected. They suss out suspect corners and sweep them of debris before Bucky finally pulls Brian back up to the top of the climb with a rope, similar to how jet skiers tow big-wave surfers into swells. Then it’s a simple fist bump, a few words of encouragement, and the two are off, with Bucky following Brian at close range, capturing “all the madness” on a gimbal-mounted GoPro.

Despite their immediate success, Brian had something bigger in mind: a descent that, if ridden right and filmed correctly, would take him to the limit. He found it in Tuna Canyon. Dropping nearly 1,700 feet in just over four miles and featuring roughly 50 bends, some of them blind and many of them pitched precipitously above the canyon floor, Tuna is the holy grail of L.A. descents. It’s a place where the best local riders test themselves, in large part because of its one-way status, meaning the entire road can be used in a quest to set the fastest time. Ostensibly Tuna is one way downhill, but there’s no spike strip at the bottom to keep someone from driving up it. Rafael had the KOM, and Brian knew that to significantly beat it he would need to “put a bunch of runs down Tuna,” as well as position radio-equipped spotters at each end of the segment for safety. Thus began an obsession that would consume a year and a half of his life.

Before Brian became a filmmaker, he was a bike racer. As with everything in his life, his approach to racing was as unconventional as it was obsessive. There were the 10 or so years of racing during his messenger days, of course. Then, while vacationing in Mexico in 2012, he started helping out a friend who was organizing the 2014 Cycle Messenger World Championships, to be hosted in Mexico City. He wound up staying six years, during which time he started a messenger business and eventually met his wife, Ninna, a Californian with dual citizenship.

It was a joyful time, though a lean one. Brian was already used to living in the financial gray area of a contractor, and he’d endured many of the dangers that messenger work entails. He’d had angry motorists try to run him off the road and knives pulled on him. One time a drunk driver got out of his car at a stoplight and approached him brandishing a gun. But Mexico City posed a different set of challenges. Work was scarce, traffic fierce, air pollution so thick he could practically feel it deep in his thorax. On top of that he was broke, sometimes so broke he had to skip meals. The threat of homelessness was always on the horizon. As a way to save money and get healthy, Brian put drinking on hiatus and rode his bike more and more while taking a keen interest in fixed-gear crits, like the Wolfpack Hustle and Red Hook.

“I decided that if I got a chance at one of those races, I wanted to win it,” Brian says, reflecting on the uncertainty of those years and what a victory in a race might represent. Though never one to have an exit strategy, Brian began to view fixed-gear racing as perhaps a way out of his predicament. “I wanted to prove a point straight away and get some support.”

Picture Brian as he climbs out of the tumult and smog of Mexico City on his track bike, pedaling high into the Ajusco-Chichinautzin mountains, putting in 100-mile rides all on a single speed. Wheeze alongside him as he ascends upwards of 7,000 vertical feet, grinding away on a 16-tooth rear sprocket, and then coasts down the descents with one foot on the top tube and the other on the back tire to brake. Smell the hot rubber, the heavy petroleum vapors of baking blacktop. Imagine Brian coming home, some days without enough money for food, and doing box jumps to build up the power he thinks he’ll need to win a race he’s not even sure he’ll ever have the funds to get to.

Classic hero’s journey stuff, and so, as you can guess, Brian got the scratch together. He showed up at the 2014 Wolfpack Hustle Civic Center Criterium in L.A. so fit he wound up attacking off the front with four laps to go and soloed in for the win. Racers, fans, promoters, and brands all took note. Leader Bikes sponsored Brian, and that support enabled him to become a regular on the Red Hook Crit circuit, racing everywhere from Brooklyn to Barcelona. By then Red Hook was an established event, with major sponsorship bucks and a field that occasionally included World Tour riders. To keep competitive among guys who could lay down way more watts, Brian relied on his technical ability, employing skills he’d honed from years weaving in and out of traffic with time-sensitive packages in his satchel.

“Safa is a world-class bike handler,” says Red Hook Crit founder David Trimble. “But he’s not as fit as the elite level riders, so he was always compensating with his handling skills.” Brian notched some top 10 finishes in the Red Hook series, and as Trimble points out, he was always animating the race, often attacking on a whim and leading before the big names got down to business, or riding off the front any time it rained and the track got tricky. He also made a name for himself after the races concluded.

“He seems calm, like he has it together, but he’s pretty wild,” Trimble recounts and starts laughing. “I remember in Barcelona he got so wasted at the after party that he passed out on a city bench with his bike, and he woke up and everything had been taken from him. I think even his shoes were missing.”

Beyond the attacking and the partying, however, Brian exhibited a thoughtfulness, Trimble is quick to point out, a yearning to do something both within the oddball fixed-gear racing scene and yet somehow beyond it; to create something that didn’t require him pinning a number to his jersey. Trimble talks about some of the writing Brian did for them, which in the end wasn’t quite what they were looking for. He shot a few films as well. Each video consists of on-bike race footage set to rap or hardcore, and one features a trippy animated overlay. It’s pretty standard stuff, amateur when compared to what Brian produces now, but one can sense a desire behind the lack of cinematic skill—a groping in the dark, a need to communicate, a guy trying to figure out where he fits in.

In the span of 10 seconds Brian cheats death once, maybe twice. I don’t know if I’m being sensational or honest when saying this, but I lack the stomach to rewatch the clip, so you’ll have to take my word for it, or click over to YouTube to see for yourself.

I’m talking about Tuna here, Descent Disciples Vol. 9. Though it’s only five minutes in length, the video elicits the same hand-wringing anxiety of watching a film like Free Solo. Much like Alex Honnold’s climbing defies logic, so too does Brian’s descending, leaving the viewer to second-guess if he’ll actually make it to the finish.

Before we go there, however, let’s get a few details out of the way, all of them impressive on paper but paling in comparison to the actual footage. Yes, Brian hits 58 mph while crouched in a super tuck. Yes, he barely stops at the PCH intersection. Yes, of course he sets the fastest time down Tuna, not only by Strava standards but also up against the record established at the professional Red Bull Road Rage event in 2005, which Brian had earmarked as the true standard to beat.

Okay, so now for those close calls, those near-death experiences, however it is one categorizes what they’ve witnessed. The two incidents happen about a third of the way through the five-minute video, which represents a master class in the high-wire act of road bike descending. It begins with a turn to the left, in which Brian carries so much speed out of the corner that he nearly collides with a rock wall, and ends, perhaps 100 feet later, when he banks around a blind bend back to the right, where the road suddenly narrows, causing him to come within what appears to be millimeters of clipping his front wheel on a concrete barrier. Had he struck it, he would have probably vaulted into the wooded ravine on the other side. It says something about the clip in general, and this section in particular, that moments later, when Brian is forced to ride up onto the far berm of the road, threading a needle that’s nauseating in its narrowness, the move barely registers, so inured has the viewer become to the risks at hand.

Both incidents could be chalked up to sheer luck. But the audio tells a different story. As in all his videos, Brian narrates the descent with a nonchalance that borders on monotone, calling out troublesome turns, telegraphing the speed he’s about to hit before he sprints out of the saddle, swaying the bike viciously beneath him as if he were on the flats rather than descending a road so rough and steep even seasoned riders would approach it with two fingers squeezing either brake lever. “Whoo!” he shouts, not after narrowly clipping the rock wall but before it. “Oh, yeah!” he says moments later, but again it’s milliseconds before what appears to be a near collision with the concrete barrier, not afterward or even in the moment. Suddenly everything computes. Of course, it’s so obvious, though this realization hardly diminishes the athleticism on display. Brian isn’t reacting to the road and all the obstacles it throws in his path, he’s anticipating them.

“If I am pushing right up to the white line on the edge, it’s because I am placing the bike there, not because I am running out of road,” Brian says. “A lot of people misidentify what I am doing there.”

Before filming, Brian estimates he rode Tuna some 80 times, memorizing every turn, every ripple in the tarmac, rendering the whole thing rote before Bucky hit “record” on the GoPro. This allowed Brian to max out each corner, to extract as much speed from Tuna as was humanly possible, laying down a time he reckons even a renowned World Tour descender like Vincenzo Nibali might find hard to beat.

Again, however, it’s the visuals that matter. Sport is, after all, entertainment, and while Brian’s isn’t done live in front of fans or sanctioned by any league, the overall effect is no less mesmerizing than the feats performed by professional athletes earning millions of dollars. “All right, fasten your seat belts,” he tells YouTube viewers as he enters the lower half of Tuna, golden light shooting through the green canopy of trees, the picture darkening the deeper he drops into the canyon. Brian bunny hops over a wide crack in the road at nearly 45 mph. He lifts his chest out of the super tuck, “air braking” through a series of corners while knocking overgrown roadside weeds out of the way with his shoulder, deft as a downhill ski racer brushing a gate. He surges through a straightaway, as if propelled by a motor, almost dropping Bucky, and in this moment one can see Brian stretching himself, stretching the sport, stretching our own narrow conception of what constitutes professional cycling and leading us—if we’ll only let him—to where it might go.

Brian admits that Tuna represents the apotheosis in terms of his descents. It’s a ride that rendered him right on the edge, and a risk—at least on camera—that he’s not too keen to take again. “I don’t want to put people in that position…” he says, voice trailing off as he considers the most extreme consequences of attempting anything crazier than Tuna. “I wouldn’t want Bucky to have to sit there with me while I die.”

“Zero! Zero!” Rafael da Silva says, laughing, when I ask if there’s a chance he’ll try to take his Tuna KOM back. Sometimes he worries about his friend, knowing how much he rides and how he lives life with a day-by-day mentality. But mostly Brian’s cycling fills Rafael with FOMO. Says David Trimble: “Watching his videos makes me want to do what he’s doing. For me they promote cycling in a way that makes me want to go ride and want to ride road bikes.”

Brian’s mother Sue shares this enthusiasm, telling me that she is astonished by her son’s skills and his ability to concentrate, how he seems to anticipate everything ahead while remaining completely in control of his body and his bike. Though, she adds: “I don’t think I could watch in real time.”

More films are in the works, continental road trips, perhaps a European tour. Brian promises neither, but hints that the vibe in whatever he does will be mellower. Speed, however, will still make some appearances.

“If you watch a surf movie and all the waves are three feet high, you’re going to feel like something is wrong,” Brian says, a slight grin appearing from beneath his beard. “Why would you have a cycling film where everyone is riding under 30 mph? Speed is part of the sport. It’s one of the best parts. I’m never going to shy away from that, or bow down to the way someone thinks it should be filmed.”

Oddly enough, Tuna is far from Brian’s most viewed video. That honor belongs to another clip: a simple POV piece shot down Deer Creek, well before he took that descent’s KOM. Views currently sit at 2.7 million, and yet the film, captured cruising at 40 mph, is almost leisurely by Safa standards. I hunch forward over my screen, straining to see the reason behind its popularity. Nothing stands out. No speed wobbles. No dangerous angles. Brian seems content to coast, a big handlebar bag coming into frame as he banks around a corner, rolling through a lush springtime landscape of green mountains and blue ocean.

And then Brian speaks, not flatly or awkwardly but fully, joyously.

“I’m in heaven, guys!”

He hoots. He hollers. He lets fly an unguarded scream, his voice not monotone but high, cracking: “Living life, baby! Living life to the max!”

One’s inner cynic might cringe at the clichés. I suppose Brian might, too, had he not been so present. It’s a moment he extends for the entire duration of the descent, shouting and whooping the rest of the way down Deer Creek, talking to us as if we’re all riding right beside him. There he is, this man on a bike who once had no exit plan, the messenger turned crit racer turned filmmaker, with all those emotions he had bottled up since boyhood at once cascading through him and reaching out to the rest of the world.