I arrived at my destination, locked up my beater bike, and double-checked the instructions on my burner phone before walking into the fancy new building on the Williamsburg waterfront. I gave a fake name at the front desk; the doorman pointed to the elevators. Upstairs, a tall, friendly guy greeted me at the door. “Cool kicks,” he said with a nod to my feet. I nodded back and followed him down the hall to the living room to set up. He asked a few questions, made his selections from the spread on the coffee table, and handed over the cash. I left with a sweet $20 tip, and on to the next stop I went, traveling by bike and serving the finest cannabis that sunny California had to offer to the good people of New York City.

In some ways, this job was no different than when I sold chocolate bars door to door as a kid whenever we were short on cash at home. Dad would pick us up from school and drive us back to his office at the University of Puerto Rico in our hometown of Mayagüez, where he would finish work while my siblings and I knocked on every office door on campus selling M&Ms and Hershey bars for a dollar apiece.

My parents didn’t mean to put us to work at such a young age, but they valued a good education, and in Puerto Rico that can come at a great cost. So while they kept second jobs on evenings or weekends, we didn’t mind helping where we could.

Meserole Street to Metropolitan Avenue. Metropolitan to DeKalb. DeKalb to Graham Avenue, and so on. Ten minutes to 9 p.m., and it was time to close out. Through darkness and city lights, I headed back to the office in Bed-Stuy and texted our dispatcher, Ariel, so she could let me up. I joined the other techs and, as usual, we shared our day’s highlights and stories of the quirky clients we met. I counted the cash, about $1,300—not bad for a weekday. Ariel took the money and paid my commission: $160, plus a little extra for selling over my quota, adding up to $200. Then she slid me an eighth of Purple Kush, a freebie I would later sell on the side for the extra cash.

This wasn’t how I imagined I’d be spending the summer of 2012—moonlighting nights and weekends as a traveling “technician” for Apex Tech Services while working full time as an assistant designer in my first job out of the Fashion Institute of Technology. But I had a massive pile of hospital bills, and my $32K-a-year 9-to-5 job couldn’t begin to cover them. It was perhaps unorthodox, but I was desperate and young with no financial safety net, and I had weighed the risks carefully. I would do it all over again because it was the beginning of a journey of self-discovery, and how I found my true love for riding bikes.

I’m no stranger to odd jobs. In elementary school, I made and sold macramé bracelets and beaded jewelry and delivered phone books on weekends with my mom. At age 16, I had my first “real job” at the Mayagüez Zoo, where I spent my time tending the butterfly garden and making sure visitors didn’t get poop-sprayed by the hippo. During college at the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras, I was a personal assistant to a tango dancer who once claimed to have had a vision from my past and told me that I’d been a hatmaker in a past life. And for a couple of months, I worked night shifts at the mail facility in San Juan’s Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport, sorting letters and packages and sending them on their way to their destinations. I was saving up so I could take an introductory workshop at Ropajes, a small fashion design school in San Juan. That’s how I made my way from Puerto Rico to New York City in 2010 to study fashion after four years of journalism school. The pivot wasn’t random. Somewhere, between jobs, I had competed in Puerto Rico’s knockoff version of Project Runway, and my mentor and teachers urged me to apply to schools abroad. So I did. (And then I actually ended up making hats for a few years, but that’s a story for another day.)

Brincando el charco (jumping the puddle) is what we say back in la Isla when someone moves from Puerto Rico to the United States for school, work, or a different quality of life. This colloquialism attempts to make the Caribbean Sea seem small enough that anyone could easily hop over to the U.S. and start a new life. Despite how much the phrase minimizes the action, it is a difficult and emotional decision to make for any Puerto Rican. The puddle itself is not the challenge–the real test lies on the other side and what you do with your life there. There are many songs written about it; one of the more famous is “En mi Viejo San Juan,” composed by Noel Estrada and popularized by Javier Solís. Estrada wrote it in 1942 for his brother, who had been deployed to Panama during World War II and was feeling nostalgic for his motherland. The song became an anthem of Puerto Rican emigration to New York.

The song also implies a broken promise, even betrayal, some might say. It encompasses a heavy feeling that many Boricuas all over the world live with: the guilt over leaving, and regret for not visiting enough or never making it back. Listening to this song from a young age can prepare most Puerto Ricans for the short voyage, convincing them that our hearts can remain home while we live our lives elsewhere. It taught me to be careful of the promises we make, because leaving your heart to sit out like a lighthouse waiting to guide your return home doesn’t seem fair. So I took what I could with me, heart and all.

But it didn’t make it any easier.

I arrived in New York on a cold February day and moved directly into the FIT dorms on 27th Street and 7th Avenue in Manhattan. Once I settled in, choosing to commute by bike was not hard. Dirty subway stations and delayed trains tested my patience, and there wasn’t much to see underground. Fashion school was hard work, but fun, and I made my first friend, a true New Yorker from Kew Gardens, Queens, who laughed and talked just like Elaine Benes from Seinfeld. Visiting Linda in Queens was one of the first “long” rides I made by bike. Crossing boroughs, bridges, and neighborhoods, learning how big the city really was, and making connections in my head between lyrics and the actual places they sang about—something that can happen a lot in New York. I would ride by the Flushing Cemetery where Louis Armstrong rests, and as I reached Forest Hills, Paul Simon’s “Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard” would come to mind.

In April of 2012, a year after graduating FIT, I was riding my bike home one Saturday night. My date and I had watched a Gotham Girls’ roller derby game at Hunter College, then rode to a birthday party at the Caribbean Social Club in Williamsburg. After a lot of dancing and drinking, on our way back to my apartment—a short five-minute ride to East Williamsburg—I hit a pothole on the slight downhill where Borinquen Place fades into Grand Street. The bump sent me over the handlebar and I landed face-first on a manhole cover. I was instantly knocked out. A woman who saw everything from her taxi called 911. She was kind enough to store our bikes in her apartment after paramedics arrived and took us to the emergency room at Kings County Hospital Center.

The bike I was riding that night, a refurbished 1970s maroon Raleigh road bike that I’d brought with me when I “hopped the puddle,” had been a gift from my dad. Back in Puerto Rico, after I had finished college, I would meet friends on Thursday nights for a casual group ride called Bicijangueo (bike hangout). We would ride bikes to the park, to chinchorrear (bar-hop), crash a gallery opening, and go anywhere we could pedal to. When I moved to New York, riding this bike was simply the most affordable way to get around. And I discovered that it was the best way to make friends with interesting people from all walks of life who had unique and wild stories. I could feel my soul leaning forward seeking momentum.

But it all came to a full stop that night. The damage from landing on solid cast iron resulted in multiple fractures to the right side of my face and a torn ligament on my right shoulder. I didn’t register any of it, and I try not to think too much about what that pain would have felt like had I been conscious.

My right jaw and orbital bone, fractured in three places, were skillfully mended with little iron plates and screws that still feel funny when rain is in the forecast. My shoulder looked a bit odd, too, like a bat’s wing, but the separation wasn’t severe, and I could do almost everything I could do before. That’s how I found myself back on a bike two months later, slinging weed to cover the cost of lost wages, high co-pays, and months of physical therapy.

To some, the comeback seemed rushed, but I needed to keep riding to take care of myself. In more than one way. The accident brought to the surface questions that frightened me, about whether I belonged in NYC, about who I was and why I left one island for another. I thought that if I just kept moving, everything would be all right. If I kept moving, I couldn’t be pinned down, and I wouldn’t have to decide who I was or where my identity resided. I could find the answers along the way.

As long as I got back on that bike, I knew I would be fine. I felt brave. I felt alive. I made enough money to pay all my hospital bills and have a little fun. Self-sufficiency gave me comfort, while riding offered the freedom of being neither here nor there.

The job came with code words and nicknames meant to protect us from knowing or revealing too much. My nickname was Dash. The owner of the “serve,” as far as I knew, was this granola-head type we called Blondie; he was pretty chill, smart, and a good conversationalist. Once, he took the whole team skydiving as a gift for a good quarter in sales. Blondie’s right hand was a guy called Pete. Pete was like a dad; he always had good advice and could make anyone feel at ease. He also trained in martial arts and would show us a few self-defense moves here and there. You know, just in case. I never needed them. But others weren’t so lucky. Kayman, one of the more senior techs, got mugged right outside one of his stops—he covered the wealthy “nice” neighborhoods in Manhattan. Two other techs were followed and mugged, which turned into a whole thing with Blondie tracking down one of the burner phones (inside a bag the muggers took) and following the robbers down to Roosevelt Island.

I loved the job, and I was good at it. The secrecy, the constant movement, the people, and all the other benefits that came with it. It felt like play. Following a map, riding around, never staying anywhere for too long, waiting for the next text simply stating a name and a place to be. I grew up playing sports, but this was different. I moved quickly and diligently on the bike, learning my way through the city one shift at a time. I’d tell doormen I was Carla, Raquel, Vicky—a “friend” of whomever I was delivering to.

In between calls, my go-to spot in North Brooklyn was Red Lantern Bicycles on Myrtle Avenue, a cafe/bar with a bike shop in the back. You could always bring your bike inside, and they had a fat cat named Landshark who loved attention. It was during these breaks that I got friendly with a few bike messengers, fixie kids, and their friends. People who invited me in simply because I liked riding bikes too.

Getting to know NYC’s messenger family was my first introduction to cycling as a lifestyle. The messengers carried themselves with an air of freedom and independence. They’d mark eight-plus hours in the saddle with Tecates and tequila shots at the dive bar on South 6th in Williamsburg. They’d arrive rowdy and exuberant, skidding to a stop and then piling their bikes against the fence, forming a sculpture that would later disappear. Inside, laughter, loud voices, the smell of barbecue in the yard, and shared stories of a day’s work. Hardworking people who knew how to have fun. I could relate.

“A park, a coffee shop, a bench, anywhere—the whole city is my office,” one of my new acquaintances said. We shared a love for bikes, and for how bikes connect us to the places we live in and pass through.

On one occasion, a good friend asked me why I wasn’t afraid of riding bikes again, and I was not prepared for the question. I couldn’t explain it then. Riding bikes was just all I wanted to do at the time. It was how I was making friends, how I moved and explored this place I had once been so scared of.

As a daughter of Borinquén—the native name of Puerto Rico—I sometimes wonder if it was a coincidence that my accident happened on Borinquen Place where it turns into Grand Street. And the fact that the very first day I got back on the bike coincided, unintentionally, with the Puerto Rican Day Parade, well, it makes me think of things like fate, destiny, metamorphosis…

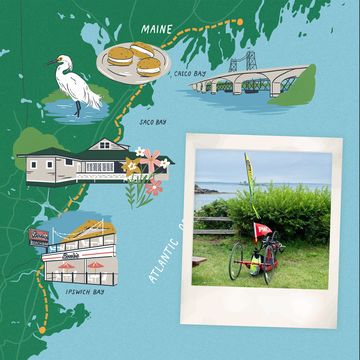

Eventually, after a few techs were assaulted, the serve became too risky and I feared for my safety. I had finished paying my bills, so I left. But I couldn’t just quit riding. My fixie connections led me to the Kissena Velodrome in Queens for twilight racing, where I met Ayesha McGowan—at the start of her incredible cycling journey. Then came road racing in Central Park, where I would have to be on the road by 4:30 a.m., riding north on 1st Avenue, spotting people as they headed home from a night of working or partying while the rest of the city slept in. I joined Radical Media Racing, a development team with good connections to the cycling industry. That’s how I met Ina-Yoko Teutenberg, an absolute legend of the sport, at a training camp in California—my first time there. Before I knew it, I was consumed; it felt like a map just kept unfolding, revealing new paths. In front of me were roads and trails that begged to be explored, and people with stories I wanted to listen to.

“If you have a bike, you have friends everywhere,” I read recently on the ’gram. After years of embracing this way of life, I have begun to think of cycling as an archipelago of islands. Small, quirky, and unique communities, all in love with the same thing: freedom of motion and a constant need for connection. Connection with the earth, roads, trails, our bodies, and others.

Not all journeys are a straight line. Sometimes you have to wander to avoid storms, or stay put for a little rest. Today, I ride so that I can move through life fast enough that I can only dwell in the moment. I ride to make my body and mind so tired, so vulnerable that I can’t fight my own discovery; to disarm the inhibitions that keep me from exploring places, people, and my true self.

Dedicated to my Abuelo Roberto, who once left the Island for NYC but life eventually brought him back home; and to his daughter, Titi Ely, who was always there to lend an ear without judgment.

Rosael is an avid cyclist and seasonal runner who is in the pursuit of getting more people on bikes. All bodies. All bikes. As the editor of special projects, she gets to work on initiatives that further engage our audience and provide additional value to our readership. Lately, she has been dipping her cleats into gravel racing and other off-road adventures.