There’s a video of Moriah Wilson from August 1, 2021, at Rooted Vermont, the only race where her family got to watch her compete professionally. It’s six seconds long, taken through a car window.

Moriah charges across a forested hillside from right to left, fast enough that it’s hard to make out she’s climbing. Her jersey flashes green and white, a blur of gravel beneath her. In the background, an unbroken canopy of maple, birch, and evergreen. A thick blond braid falls from her helmet like a rope. Moriah’s limbs are splayed over the bike frame, legs pumping. As races go, it had been a rocky day: she’d lost her chain, gotten a flat, and nearly missed a turn, falling well behind the leading women. Now, she was battling back toward the front. Each time race vehicles pulled ahead of the pack and waited for it to pass, here came Moriah, overtaking another rider.

Join Bicycling for unlimited access to best-in-class storytelling, exhaustive gear reviews, and expert training advice that will make you a better cyclist.

The video was taken by a woman she’d never met. Caitlin Cash worked as a project manager for a tech company in Austin, Texas. But a year into the pandemic, she and a group of friends had bought an old inn together in East Burke, a tiny town in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, about 45 minutes from the Canadian border. The Kingdom Trails, a network of a hundred miles of singletrack, was just across the street. For Cash, who raced on weekends and had a close circle of cycling friends, the inn was one more way to integrate her passion for biking into the routines of her life. That weekend at Rooted, she was pitching in to help the organizers with social media.

As she watched Moriah race, she was moved to tears. Subtly, a bit mysteriously, but undeniably, Moriah was smiling through the grueling effort. Who is she? Cash wondered. So much poise, so much grace, so much grit.

Later that day, Cash found Moriah’s family cheering along the course and talked with them long enough to realize they were neighbors back in East Burke. Over the next couple of months, as she vacuumed, repainted, and made trips to the store, she found herself stopping to chat with Moriah’s mother, Karen, in town, or going on bike rides and stacking firewood with Moriah’s brother, Matt.

In late October, Cash traveled to Bentonville, Arkansas, to do the 53.2-mile “Lil Sugar” at Big Sugar Gravel and screwed up the courage to introduce herself. The 103.8-mile “Big Sugar” was the first big race Moriah, known as “Mo,” had won. That night, Cash approached her in a crowded bar. Mo met her eye through a scrum of admirers and gave a tiny, friendly wave. “Cash!” she said. “I’ve been looking forward to meeting you!”

Within a few weeks, Mo was crashing in Cash’s apartment in Austin, stringing her laptop cord across the kitchen, swapping career advice and wine recommendations. They didn’t ride together—Mo was tough to keep up with—but they both loved to cook; Cash an empty-the-fridge kind of chef, Mo, a methodical gourmand who shopped for the ingredients in each new recipe. Mo worked from the kitchen, Cash from the loft, and during the day, they kept up a steady banter workshopping the wording of texts and emails from either end of the stairs. A few weeks later, Cash was up in Vermont again, at the Wilsons’ for Christmas, pulling lip balm and Toblerone from a stocking that had belonged to Mo’s grandfather. All the while, Mo was winning almost everything she lined up for: Big Sugar. Gravel Hugger Rock Cobbler. Second at Leadville and Mid South. First in the Belgian Waffle Ride by more than a half hour, first again at Sea Otter. In May, she was back in Austin, staying with Cash, and preparing for Gravel Locos on May 20th in nearby Hico, Texas, another race in which she was, yet again, a favorite.

On the morning of May 12th, Karen Wilson looked up from the loose dirt of her potato beds: a police officer was pulling into the driveway. He said, in so many words, your life will never be the same. Her daughter, Anna Moriah Wilson, had been shot and killed in Austin, Texas, the night before.

Back in Austin, Cash waited for the phone call from Karen she knew would come. The previous evening, when she’d returned home from dinner with friends just before 10 p.m., Cash had walked into her apartment and found Mo unresponsive and bleeding on the bathroom floor. She’d frantically called 911 and began CPR. Paramedics arrived and tried to save her, but Mo was pronounced dead shortly thereafter.

As Cash waited for Mo’s name to become public, she braced for the moment when the world found out about the horror she was trying to make sense of. She wanted to support the Wilsons, but there was stuff she couldn’t bring herself to talk about, photographs she couldn’t bear to look at. For Karen, and Mo’s father, Eric, the bigness of the loss, its permanence, its totality, hit them with a force that was hard to explain at human scale. “This is like the 9/11 of our life,” says Karen. Even in the depths of grief, the Wilsons had things to do: conversations with police, and then, the prosecutor. Decisions about their daughter’s belongings. A cascade of media requests. There was even, only days after Moriah had been killed, a statement to be crafted to reassure fellow cyclists at Gravel Locos that what Moriah would have wanted most was for them to race their hearts out.

Still, it was hard to feel like competition mattered. In Hico on May 14th, the race took off slack and somber, a two-wheeled funeral procession for the first eight miles, the only way the riders could reconcile what they were supposed to be doing with the crater in their midst. “There was just no racing in me, I mean, the entire 150 miles,” says Sarah Sturm, who raced alongside Mo for Specialized.

In the days that followed, there were times Cash felt incapable of getting dressed or remembering to eat. The wind felt different. Colors were different. Time dissolved. She tried to reassure herself that she’d been there for Mo until the last. With tears in her eyes, pausing on each word, she told me during a video call in October: “I did not give up.” Laying low at her father’s house in another part of Austin, Cash sat and stared at the driveway, wondering if the bullets had been intended for her instead. She called the police repeatedly, frantically, looking for any information about suspects or a motive.

As word began to spread about Mo’s death, unsettled female cyclists sent warnings to one another, worried that Mo had been tracked down by someone watching her workouts on Strava, and questioned what was safe to post on Instagram.

Improbably, Mo’s name began to ricochet around the world at the center of a plot that felt utterly disconnected from the person she had been. “Love triangle,” Sturm says. “If I see that printed in one more headline, I’m going to scream.”

The details seemed ripped from the tabloids: On the afternoon of Wednesday, May 11th, Mo went with Colin Strickland, a top men’s gravel racer with whom she’d had a brief romantic relationship, for a swim at the City of Austin Deep Eddy Pool, then dinner at a nearby restaurant. Strickland dropped her off at Cash’s home at around 8:30 p.m., then left on his motorcycle. Within two minutes of Mo’s arrival, security cameras on the block captured footage of a dark-colored SUV driving past the building with a large bike rack on the back. Police later reported that the vehicle—a black Jeep Grand Cherokee—was registered to Strickland’s longtime girlfriend, Kaitlin Armstrong, and that Armstrong owned a gun—a gift from Strickland—the ballistics of which matched the three bullets that killed Mo.

The next day, Armstrong was arrested and held on a misdemeanor warrant for not paying a Botox bill in 2018, only to be let go because her date of birth didn’t match the date recorded on the warrant. That Friday, Armstrong sold a black Jeep Grand Cherokee at a Carmax in South Austin for $12,200.

On Saturday, she flew out of Austin, changed planes in Houston, and boarded a Southwest flight to New York’s LaGuardia airport. The very next day, using someone else’s passport, Armstrong traveled to Costa Rica, stopping in Jaco Beach before she made for Santa Teresa, a vacation destination on the Pacific coast for the likes of Tom Brady and Gisele Bündchen.

Strickland, meanwhile, was interviewed by investigators and later issued a bizarre statement. The website for the vintage trailer business he’d shared with Armstrong was taken down. Inevitably, as the search dragged on, brands made their awkward entry into the fray—sticking by Strickland, or dropping him, or posting tributes to Mo. It was hard to know what to think. “There are so many questions, and the first person you want to blame is Colin—because he’s the thread,” Sturm says. “But he didn’t do the thing.”

As American authorities widened the scope of their search, Armstrong spent the better part of a month bouncing among hostels and yoga studios in Santa Teresa using several aliases, according to the United States Marshals Service.

On June 29th, Costa Rican authorities going door to door found Armstrong at the hostel Don Juan with her red hair dyed dark brown and a bandage on her nose—a wound from what she said was a surfboard accident.

Armstrong was brought to San Jose, where she eventually acknowledged that she was, in fact, the fugitive investigators were looking for and was then transferred to the custody of U.S. Marshals, who brought her back to Texas. She remains at the Travis County detention center, where she is being held on homicide charges with a $3.5 million bond. Her trial has been set for June 2023.

Grief for those who knew Moriah through cycling became a strange untangling. She was kind, retiring, a baker of banana bread, a lover of all things maple, a week away from turning 26. How can you shield the memory of someone like that from the shadow cast by her murder?

You might say that all this is demonstrative of another tragedy, or even many entangled tragedies, both private—in that Strickland lied to Armstrong about his whereabouts on May 11th, and had deleted text messages from Mo and disguised her number in his phone—and public, in the sense that no one sets out to become the kind of person capable of shooting someone else to death. There’s no monopoly on terrible consequences from a terrible event. Yet in its own way, the temptation to fit a suspect into the frame of Mo’s life is a tragedy that compounds the loss. It’s the same with so many senseless killings—the feeling that the world has not only robbed you of a person you loved but forced you to grapple with its cruelty and ugliness in a way that will forever be tied to their memory.

For Cash, each day began with a Google search: M-O-R-I-A-H W-I-L-S-O-N. If she had no choice but to grieve in the shadow of tabloid intrigue, she wanted, at least, to know what information was out there, what cruel detail was being speculated about.

Glam Yoga Teacher Says ‘NOT GUILTY’ of Love Murder, Secret Life Revealed.

Costa Rica Arrest Photo Reveals Accused Cyclist Killer’s Disguise.

Alleged love triangle killer Kaitlin Armstrong’s bizarre meltdown.

Day 38, and they still hadn’t apprehended her? Cash learned to avoid the Daily Mail, and to set a goal each morning to make it to dinner.

The Wilsons tried to shield themselves. Karen shut out the internet and pored over her daughter’s journals instead. “I’m totally focused on Moriah,” she says. “And on surviving, and breathing, and eating.” Eric stayed in touch with the prosecutors and culled the news when he had to for information about Armstrong’s defense strategy.

Matt, who is 24, and was a week away from graduation at Vermont’s Middlebury College when his sister was killed, took the lead in communicating with the outside world. Grief ushered in a new set of questions about his future. It was daunting to think about the life he’d imagined postgraduation, or even to decide if he still wanted the same things. There was talk of a foundation, some way to secure a public legacy for a sister who should have had a lifetime to secure it herself. Is that what he wanted to do? He still wasn’t sure.

The night after the race in Hico, Matt lay awake feeling as though Moriah was plugged into his brain, not a voice so much as a presence, responding to his thoughts before they were fully formed. He roused himself in the morning and piled into bed with his parents where they held each other and cried. It was their new routine. “Did you feel that last night?” they asked each other.

Unbound Gravel turns the downtown of Emporia, Kansas, into a festival. When I booked a trip to the Flint Hills a few days ahead of the race, this past June, the closest room to be had was 25 miles down the interstate. The hills were a lush green, the rivers a swollen, deep brown. On the way into town, you pass towering bean silos that stand in for a skyline and a sign that reads: “Righteousness makes a nation great, but sin is a cancer to all people.” Downtown, the sidewalks were clogged with banners and people carrying cups of beer at 9 a.m. Carrying gold pom-poms, Emporia State University students posed for pictures at the starting line.

Mo’s absence was palpable. The field had taken a deep hit: In 2021, Unbound came at the early end of her meteoric rise through the sport, and she’d finished ninth. Now, after the season she’d had, as one photographer on the course put it: “That’s a podium spot that would have been filled.” Event organizers distributed ‘Ride Like Mo’ stickers to all 4,000 participants to display on race day. Among the light poles festooned with posters of past winners, Colin Strickland’s likeness was nowhere to be found.

The day’s conditions were fast—cool and dry, without much wind—until all of a sudden, they were dreadful. “I thought of Mo when I was hurting,” Lauren DeCrescenzo told me after the race, reclining in the shade of a pop-up tent near the finish line, helmets and water bottles and shoes littering the pavement nearby. She’d finished second in the women’s field, and she teared up as she recapped the silent pep talk she’d given herself as the course turned to mud under hard rain, some 150 miles into the 200-mile course. “It’s a privilege to be able to do this,” she’d said. “You chose to come here, and—Mo should have been here.”

During the announcer’s patter over the PA as the intervals between finishers stretched, he mentioned in passing that the women’s winner, Sofia Gomez Villefane, had started the day ranked second in the season-long Lifetime Grand Prix series—and finished in first. What he left unsaid was that Unbound was only the second of the six races in that series: Moriah Wilson had won the first.

It took months for Cash to outrun guilt and confusion, the feeling that things might have been different if she’d come home earlier, or if she hadn’t gone out at all. She’d resisted leaving Mo’s side for as long as possible that first night and got to the police station in a daze around midnight. It was only later she realized she’d been questioned not just as a witness, but as a potential suspect. Cash’s home became a crime scene, and, once the media got hold of an arrest affidavit revealing her name and address, a public destination. Reporters lurked by the front door. There were attempted break-ins. She pleaded with police for permission to go back to retrieve some of her things. When it finally came, she could hardly bear to cross the threshold.

For Karen, the first weeks of summer passed in a blur. In June, Cash brought a single suitcase with the things Mo had with her in Texas. Friends drove Mo’s car from San Francisco to Colorado, then shipped it from Colorado to East Burke, Vermont, packed with stuff from her apartment.

Moriah’s belongings sat undisturbed for days. Slowly, as she found the strength, Karen also found comfort from holding the things her daughter had held, burying her nose in the clothes she’d worn. Near the end of her life, Moriah had been especially taken with the book The Second Mountain by The New York Times columnist David Brooks, which centers on the challenge of balancing life’s first mountain—ambition, career, family—with the taller one behind it: the quest to live a moral life. “I’m not gonna do the first mountain and the second mountain,” Mo had told a friend. “I’m gonna do both mountains at the same time.”

Leafing through Moriah’s dog-eared paperback, Karen hung on each of the underlines Moriah had made, clinging to every scrap of her daughter’s mind. When Cash’s birthday came around, she bought another copy as a gift, and went through it in ink, underlining the very same passages.

Moriah and her brother were reared on the slopes of Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, dominated by a handful of families known as ski-racing dynasties. Moriah’s father, Eric, had grown up nearby and skied for the U.S. national team; his sister, Laura, competed in cross-country skiing in the winter Olympics. Moriah entered her first ski race at 8 years old. On race days, the Wilsons would leave home in the dark and stop on the side of the highway for an Egg McMuffin—a rare indulgence.

Among the competitors Mo faced on the local youth skiing circuit was Mikaela Shiffrin, who would go on to be the best in the world. Moriah, whose best result was seventh in downhill at U.S. nationals her 11th grade year, wasn’t a skiing prodigy by the standards of Northern Vermont, but she did have the drive to work as hard as anyone. “Ever since she was a little girl, she wanted to wear one of those green Dartmouth ski suits,” Karen told me.

In the world of United States skiing, Burke Mountain Academy is a kind of cousin to the Florida training grounds where Andre Agassi and the Williams sisters honed their ground strokes, a high school where the loftiest goal isn’t Harvard or MIT so much as the Olympics and the World Cup. The student body is talented, tiny—no more than 15 or 18 kids in a class—and, due to skiing’s expense, largely white and well-heeled.

Moriah was the rare local kid who’d had the run of the school since she was born, when her father was a ski instructor there. She took part in Burke’s winter ski sessions as a middle schooler and entered full-time in ninth grade, a skinny 14-year-old with a runner’s build. Even then, coaches noted her unusual power on a bicycle. Mountain biking is a cross-training staple for skiers: low-impact but demanding of the same muscle groups. On early morning training rides, Mo seemed to thrive on hills while other riders would fall back. “All the boys would come into breakfast after the ride, and Moriah just killed them all,” says Kraig Sourbeer, a coach who dabbled in mountain bike racing after a professional career on the U.S. Ski team. Sometimes, he and the other coaches wondered if she was in the wrong sport: Whatever her talent on the slopes, it was obvious that they’d translate well to cycling.

Teachers remember Moriah’s quiet self-assurance and diligence. In a milieu defined by privilege and high-level competition, she was that uncommon breed of teenager who never groused about “duty night,” when rotating student groups mopped up and washed dishes in the dining hall, and never rolled her eyes at a difficult workout. When, early in her sophomore year, she went down on Burke’s training slope and tore her ACL, she seemed to relish the chance to dedicate more time to strength training, logging every rep in a series of notebooks in tiny immaculate handwriting. After she was killed, Burke included Moriah’s 12th grade end-of-year reflection in the school newsletter, and the whole community got a glimpse of her uncanny lust for exhaustion. “I love that painful feeling of the lactic acid washing over my muscles,” she wrote.

The ritual of reclaiming Moriah’s things was alternately nurturing and soul-crushing for Karen: the bike gear, the race bibs, the unfinished to-do lists, the Google calendar in which Moriah had plotted out her days for the next six months. As Karen unpacked the bags over the course of the summer, certain things took on a pride of place: She rested Moriah’s bike helmet on top of a stack of cookbooks in the kitchen, next to the dried-up bouquet of flowers sent by her colleagues and teammates at Specialized. The outfit she’d worn on her last ride was stored in a plastic bag until, awake in the middle of the night, Karen realized that if she didn’t take the clothes out to wash them, they’d start growing mold. Freshly laundered, they went on a hanger on the wall of Karen and Eric’s bedroom. “Sort of sacred,” she says. The oversized Dartmouth ski team T-shirt that Moriah wore to bed each night—the same dark green she’d dreamed of wearing as a little girl—Karen keeps that under her pillow.

At times, speaking to those who knew Mo felt like researching a candidacy for sainthood. She seemed cocooned from the base impulses that define so many of us. She was a thoughtful friend, a paragon of discipline, a great listener. Pressed for a memory of what passed for mischief in Mo’s world, her best childhood friend, Keara Kresser, told a story of when, in middle school, Mo had extended a break from class by leading the other kids in running extra laps around the school’s barn, when the teacher had said they should only run one.

By then, a perfectionist streak had begun to torment her, to the point that she spent long afternoons redoing a poster project after spotting a single small error. In sixth grade, her mother remembered, it got to the point that she couldn’t bring herself to write a complete sentence because of the pressure she felt to write the right sentence. “Her teachers took all her homework away,” Karen says. Moriah took to baking banana bread after she got home from school as a kind of therapy.

At a slalom race in Colorado during a postgraduate year at Burke—a common step for skiers looking to make the national team—Moriah tore the ACL in her other knee. In a journal entry written during her recovery, Mo seemed to will herself to optimism: “I know god has a plan for me.” It was the same thought, recast in a mother’s hope and grief, that struck Karen when the police showed up outside their home a week before Moriah’s 26th birthday. “God’s spirit was very much alive in her,” Karen says. “When the officer told me she had died, I instantly shot into the sky.” Looking up at the clouds, she screamed: “I know you have a plan.”

Life at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, was a version of the world Mo had always inhabited: an idyllic New England town where dozens of Burkies had gone before her, and where life was structured according to the rhythms of ski racing. She found friends, joined a sorority, majored in engineering, did well. But she was beginning to see the ceiling close in on her skiing dreams. While her knee healed, Mo spent her freshman year “free skiing” while her teammates drilled for competitions. When she finally returned to racing, she seemed always to finish just outside of contention for a berth in the next “carnival” race, as the intercollegiate circuit is called: those spots were reserved for each team’s top six competitors, and Dartmouth’s team was among the best in the country.

So Mo did what she did best: she worked. She pushed her team on long training rides in the fall and spring, spent more time in the weight room. Mo made top billing for the team, finally, in a makeup race late in her senior year. It was the last ski race she would enter. “All of that transpired into her drive—she had all of this unfulfilled podium time, and it made her want it and fight for it that much more in the biking world,” Karen says. “She wanted it so badly.”

Sometimes Cash couldn’t help but think it was stupid to be mourning a woman she’d known scarcely six months. But that’s how it was. Karen was in awe of the sisterly, soulmate feeling she observed so early in her daughter’s friendship with Cash. Their six months had been the same six months in which Moriah had gone fully pro, launched a newsletter, and decided to quit her job. Cash became a window into the moments she’d missed as Moriah began to make her mark on in the world. “There was so much I wish I had talked to her about,” Karen says.

Cash had lost her own mother to leukemia 10 years earlier, and Karen came to think of her as a second daughter. “We both have this missing piece,” Cash says. Over the summer, they spent time together in Vermont, holding each of Moriah’s things as Cash filled in trivia from weeks living in close quarters in Austin. This was her favorite sweatshirt. That face wash? Made by a Vermont company Moriah liked and had thought about approaching for sponsorship. Picking up Moriah’s toothpaste, Karen noticed the reusable plastic tube—a small daily habit, signaling a commitment to the environment. She’s using it now and gets a little reminder of her daughter “every time, I squeeze it,” she says. “There are so many things like that, where as I pull it out, it speaks to who she is.”

Mo’s first-ever gravel race was a low-key affair north of San Francisco called the Old Growth Classic in the fall of 2019. She’d spent her life using a mountain bike as transportation, and in rural Vermont, nearly all the roads were gravel. Now Mo was eager to test a lifetime of compliments about her “engine.” Just back from a three-week bike trip in Europe to celebrate finishing college, she met up with an old ski teammate from Dartmouth, and told her, “Liv, I’m in really good shape—like, the best shape of my life.” She came in second overall.

Cycling was a second chance for Moriah to reach for the athletic firmament, and, for the first time, a chance to do it on her own terms. Gravel was a welcome change from the hierarchies of skiing. At big gravel races, everyone lined up together and waited for the report of a single starting shot. They camped in vans and shared Airbnbs, traded notes on tire selection, or how to handle sketchy parts of the course. Afterward, they drank beer and sprawled on the ground together, whether they were wearing the same sponsor’s kit or not.

More than once, people I talked to told me stories about riding with Mo for an hour or two during a race, and then, essentially, telling her to leave them in the dust. At Unbound in 2021, Jess Cerra found herself beside Mo on the ragged back half of the race, pedaling furiously into the wind and occasionally passing groups together, with Mo out front, taking the brunt of it. Eventually, she blurted out, “Who are you? You’re so strong!” To Cerra, it seemed like Mo was reluctant to draft off her, in case she tried to shoot out front, so she made it clear: “I’m not gonna race you at the finish. You’ve earned that spot.”

Gravel riders often refer to the mix of nomadic training and hustle on the racing circuit as “privateer life,” a succession of photo shoots, contract negotiations, and self-promotion against the constant backdrop of intensive training. For many women, it’s also the portal to a sisterhood borne of inequity. Gravel replicates an imbalance among men and women felt across most sports: the same races, the same brands, with more lucrative contracts for the guys. And in a way that’s familiar across all kinds of unconventional professions, it’s also a life of blurred lines—are your fellow racers friends, colleagues, competitors, all three at once?

Mo and Strickland met on the racing circuit and had a romantic relationship during a visit she made to Austin in October 2021; at the time, Strickland later told police, he and Armstrong were on a break. The following January, though, according to text messages Strickland shared with police, Mo still seemed unclear about his intentions. An affidavit police drafted in support of Armstrong’s arrest noted that Strickland said he’d been helping Mo find new sponsors. It also quoted Strickland saying he concealed Mo’s contact info in his phone and admitting that he’d lied to Armstrong about his whereabouts the night Mo was killed. During questioning by police, Strickland called Mo “the best female cyclist in the country, and possibly the world,” drawing a contrast with Armstrong, who he said was frustrated at not being able to keep up on his training rides. Sarah Sturm, Mo’s Specialized teammate, sees a pattern. “Certain men in the industry wanted to almost take credit for ‘discovering’ Mo,” she says. “That hasn’t sat well with me.”

Mo spent two years readying herself for privateer life, holding down a full-time job as a demand forecaster at Specialized and crisscrossing the country on weekends, gradually growing comfortable in the skin of a professional racer, still taking red-eyes to make Monday morning meetings. The personal branding part didn’t come naturally to her—reading her postrace dispatches on Instagram, there was no way to tell whether she had finished last or destroyed the field—but that was part of her appeal too. Perhaps that was part of why the women who raced alongside her seemed to revel in her success. Mo was doing it all just to stay on the bike.

On Mo’s bedroom door is one of her old kindergarten projects: her name spelled out in dry pasta glued to construction paper. When we spoke by phone in October, Karen said she hadn’t been avoiding the bedroom really, just trying to give herself a break from breaking down. She looked in from the hall every time she left her own bedroom. But inside the door, “I end up crying pretty hard,” she said. “This morning I went in and I did fold the last bit of dirty clothes of hers that I washed. And I didn’t break down crying.”

Mo’s inner life remained a puzzle to those who knew her best, even to her mother. The first time we spoke, Karen said, smiling, that she found her own daughter “mysterious.” The family had been reading through a small stack of journals Mo left behind—a habit she kept up mainly when she was homebound, recovering from an injury. Keara Kresser, whose parents introduced Moriah’s mother and father to one another, grew up making mud pies with Mo in the backyard, laying in the grass after long summer bike rides, playing school—Mo always liked to be the teacher—and being let loose on a ski mountain with only a walkie-talkie as a tether to the adult world. Through all this, Mo’s joy was of the pensive, quiet kind. With alert, brown eyes and a creeping smile that sometimes flashed in moments of embarrassment, she seemed always to be processing the world with such focused attention that she didn’t often share her thoughts out loud. She rarely showed anger, or stress, or shared moments of vulnerability and introspection. “I spent a lot of my childhood wondering what was on Mo’s mind,” Kresser says.

As an adult, Mo grew more voluble on long bike rides, but even then, conversations tended to the practical. Long training rides were an occasion to strategize: workouts to plan, dates and car rentals and lodging arrangements to go over. “With Mo, it was . . . what does the next week, month, three months look like?” says her onetime boyfriend, Gunnar Shaw, a fellow Dartmouth ski team alum, who had often ridden with her. “Very few of her conversations were ruminations on life.”

Becoming a public figure posed a challenge to the person Mo had always been. In time, it was one she began to embrace. If being a public figure was part of being a professional bike racer, didn’t that make it just another kind of workout to master? In her last few months, she had become close with Allen Lim, founder of the sports nutrition company Skratch Labs, who formulated drinks for Mo’s races, and often prepared prerace dinners or to-go breakfasts of rice balls with eggs and bacon and a hint of maple syrup. The two liked to watch people giving speeches on YouTube, and sometimes played a game they’d devised on shakeout rides called “Tell me your life story in four minutes or less.” Each time, Allen’s prompt would change Mo’s hypothetical audience: “Okay, now you’re talking to NPR, to college skiers, to trans women cyclists, fourth graders . . . ” Sometimes Mo would sit and ponder it without responding—Mo “listened and talked with her eyes,” Lim says—sometimes she’d burst out laughing, and sometimes she’d practice saying out loud that she wanted to go to the Olympics in cycling. And that she wanted to go for her dad, who had missed his berth by one spot.

In late October, Karen returned to her job teaching literacy at Burke Town School, where she has taught for 10 years, sticking to her plan to finish the year and retire in the summer of 2023. The last time she’d spoken to her daughter, Karen had been in her classroom on a quiet afternoon in May after school let out early. Usually when they checked in before a race or about a flight home, Moriah scanned emails or went silent, too preoccupied with work and a brimming race calendar to focus. Every once in a while, Moriah would call during a low moment, overwhelmed with emotion. “I was the safe one where she could just melt down,” Karen says.

But Moriah had recently given notice to Specialized so she could race full time. And Karen could hear the change on the phone. “She was just bubbling over,” Karen says. She talked about wanting to move back to Vermont, build community in the place that had shaped her, open a café in Burke. Of everything she was looking forward to, she seemed most excited about a planned trip to Kenya in June for the Migration Gravel Race, hosted by a group of Kenyan cyclists who race as Team Amani. “To be in their space and see their world and see a different kind of life—just the whole thing, it’s so much bigger than getting on a podium here,” Karen says. “It made me so much more proud of her—as a human being.”

As the Wilsons form the outlines of what the Moriah Wilson Foundation will become, her journals have been a compass: not finished or complete thoughts, but a sense of direction. One of the entries in the last journal she kept outlined her goals for a life in cycling: to “inspire people to ride bikes and be active” and “promote positive body image awareness for women, and female athletes in particular.” Matt thinks about a story his sister told him about winning a race and watching a scrum of press crowd the top men’s finishers even as they ignored Mo and the other women. “There was so much that can be done and should be done, that she was gonna do,” Matt says.

The family put together a website with a short mission statement only weeks after Moriah was killed: To promote healthy living and community building by supporting organizations dedicated to expanding equitable access to recreation, sports, and educational programs. But Karen had been thinking of other lines from Moriah’s journals too, like simply, “Kindness and empathy can change the world.” She wants to sift through them again to immerse herself in Moriah’s thoughts, make sure the foundation’s work encompasses the things her daughter cared about most. “It’s more than getting somebody a bike,” she says. “Dollar for dollar, how can we help people? That’s gonna be an evolving question.”

The trial remains off in the distance for the Wilsons most of the time. Whatever small measure of closure or justice they can expect from a verdict, it’s still dwarfed by the everyday reality remade by Moriah’s absence. For Caitlin Cash, who still can’t escape the feeling she might have protected Mo the night she was killed, knowing she’s likely to be called as a witness means one more chance to show up for the friend she lost.

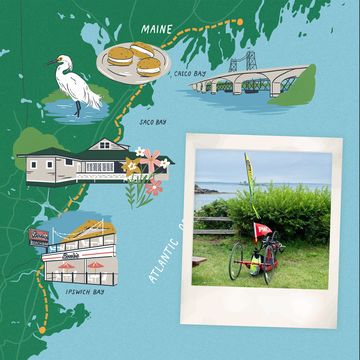

Staying close to cycling has been a way for the Wilsons to reveal more of the dream Moriah had cherished quietly and only just started to share publicly. In August, Cash accompanied Matt and Eric to the event where she’d first met the family the year before. Karen was at home with COVID-19, somewhat relieved that she couldn’t go. Rooted Vermont was much heavier with meaning now, its course pinwheeling around Cochran’s ski area in Richmond, where Matt and Moriah logged countless hours learning to hold tight turns and set an edge on ice in their ski racing days.

Cash and Matt had promised one another that they would take a break from the prerace hubbub whenever they needed to, but in the moments leading up to the race, they found themselves cracking up on the starting line. Neither one had the required functioning navigation unit; the Wilsons had lent Cash Mo’s custom pink Specialized S-Works Diverge, but she realized only belatedly that she’d forgotten to pump up the tires or charge the electronic drivetrain. Matt had forgotten to bring a bike jersey. “It took an entire village to get us on that start line,” Cash says. They couldn’t help but laugh and think of Mo, who packed every calorie she’d need into labeled baggies before she boarded a plane to get to a race. “Mo would think this is ludicrous,” they agreed.

A few weeks later, I met the Wilsons at a sidewalk café in San Francisco. Karen wore a fleece embroidered with Moriah’s name and finishing time at Leadville that Moriah had given her after the race. “She was the kind of person who did not want to advertise her time on her arm,” she told me.

Even getting on the plane and touching down in California had been a struggle. The last time they’d come West was to visit Moriah in April 2021. Now, their week was filled with firsts without her—bike rides on some of Moriah’s favorite terrain in Mill Valley, dropping in on Gunnar at home near the place they’d lived together. “People have said it gets harder,” says Eric, as the awful busyness of those first weeks subsides: time goes on, and you still don’t see the person you miss.

The week before, the Wilsons had met a trio of the Team Amani cyclists who’d managed to land United States visas. As we talked, they’d just learned that Saturday, Sule Kangangi, the team’s 33-year-old captain, suffered a fatal crash during Vermont Overland. He was the father of three young children and Karen could still picture the pretty wife Sule had shown her on his phone. It was another layer of grief, but she welcomed the thought that Moriah and Sule might get to meet in the hereafter.

The cliché is that only the good die young. But maybe the truth of loss is that the departed live on through the love that echoes among those who knew them. If you’re lucky enough to live until 90, the strongest echoes of your voice in the world—your parents, your siblings, your colleagues, your friends—may have already grown faint. Even your children will say yours was a life well-lived, that your time has come.

That’s almost impossible to say about a 25-year-old. And so, left with the task of seeking justice where none can be found, we proclaim our love as boldly as we can. Facing the cruelty of a life cut short, we mourn a hero, that their legacy might somehow avenge their death.

Back in Mo’s childhood room, beyond the door with the macaroni nameplate, Karen picks out cherished flannel shirts to give to Moriah’s cousins, bike outfits and cute jeans with holes in them for Cash. Karen and Moriah wore the same size, and Moriah’s scent is threaded through Karen’s dresser drawers now too. Each day, she chooses something to pick up and breathe in. “Sometimes it makes me cry, and sometimes it makes me smile,” she said, seeming, as we spoke on the phone in October, to do a bit of both. “I do wonder,” she said, “what’s it gonna be like when the scent is gone?”

It’s often the most emotional part of her day: the one sensation that conjures not just Moriah’s memory, or her way of being, but her visceral, physical presence. She marvels at how strong and sweet Moriah’s scent still is—even after going through the laundry—sometimes rubbing off on her own clothes, lingering longer than seems possible.

Learn more about the Moriah Wilson Foundation.

Rowan Moore Gerety is a reporter and audio producer in Phoenix, Arizona, and the author of Go Tell the Crocodiles: Chasing Prosperity in Mozambique.