Been reviewing bicycles here since 1991. No idea how many. What I can say for sure is that I liked a bunch. Loved just a few. Hated even less. Mostly, I just kind of got along with the bikes and figured out what to say about them to help people decide each time if they should buy it or not. I never took that lightly, the part about whether you should buy a bike. It’s not the whole thing but it’s a big thing, getting the right bike.

This one . . .

This bike . . .

This is a bicycle I want some of you to buy. Not all of you. Just the ones who will understand. This bike is my deep cut.

Giovanni Battaglin raced professionally from 1973 to 1984. In his debut Giro d’Italia, at 21, he finished third (behind Eddy Merckx and Felice Gimondi). He won a Tour de France stage in ’76, the climber’s jersey in ’79. (Relive that era with our 1970s logo tee!) In 1981, back when the Vuelta a España was still held in April and May, he won there, then, just three days later, started the Giro d’Italia. And won. Two Grand Tour wins in 48 days. In 1982, when he knew retirement wasn’t far off, he started Battaglin Cicli in his hometown of Marostica, Italy. In its storied years, his company employed 35 people making Columbus steel frames for racers like Stephen Roche, who won the Giro-Tour-World Championship triple crown on one in 1987. Battaglin added aluminum in 1995 and carbon in 2002—with some success in racing wins—and scaled back, then all but ceased, steel production. By then, I thought that, like many small to midsize heritage brands caught in the ravages of the economy-of-scale advantage employed by the giant companies and the trickle-down tech available through open-mold sourcing to anyone with a credit card, Battaglin lost what made it special.

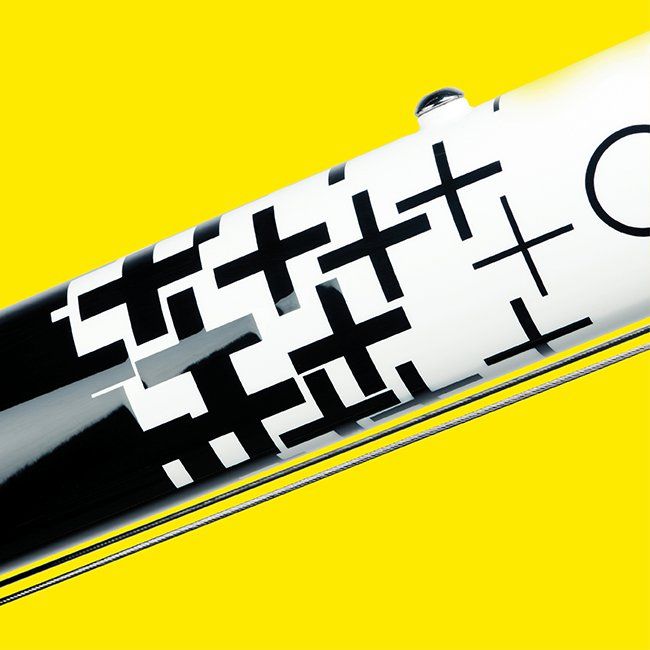

He thought so too. In 2014, with his son, Alessandro, he began figuring out what it would take to bring his handmade, fillet-brazed Columbus frames back to market. Battaglin had been known as a calculating, cool racer who kept his head no matter what, obsessed over details, and prized precision. So when he’d begun his company 35 years ago, he’d sought to put as much of the master framebuilder’s skill as he could into machines. For instance, he had one CNC milling machine built for him that makes three cuts at once, of exacting tolerances, to a down tube held in place by pneumatic vises. (Working by hand, a framebuilder would have relied on experience and a sharp eye to make the cuts, and would have needed to remove the tube several times from the jig.) All those long-idle machines were still in his factory. He dusted them off (literally), plugged them in, found a workforce (some of whom had been with him originally), sourced modern Columbus tubing (Spirit), and called his reborn operation Officina Battaglin, or, in translation, the Battaglin Workshop.

RELATED: Our Favorite Custom Bikes

The bike is astounding. A little bit because of the story, yes, and because of the storied workshop and machines from which it is birthed. But mostly because of the ride. More than any steel bike I’ve tested, it combines the classic smooth and springy quality of the finest steel frames with the agility and aggressiveness of the best modern race bikes. In this unprecedented—to me—blending of old and new, there is something absolutely familiar but unreal as you ride, like seeing a gryphon swoop by. Yet it is never ostentatious: It’s not show-offy with its response when you put power into the pedals or nerve it into a diving turn or even when you sit up and spin along with no hands on the bar and your head tipped toward the sun. It still needs minding when you promenade, and you still need to push the bike and stay on top of it when you gambol or get down to the bone—you just seem to do everything a little easier, faster, and with a little more insouciance. You could race this bike at any level, or for innumerable weekends animate and up the level of cool at coffee-shop rides.

RELATED: Best Road Bikes of 2017

Without trying, or knowing I had, I racked up three local KOMs on my test model (which weighs 16.5 pounds fully built), each requiring sustained power on rolling segments. I was just riding along, grooving on the agonistic whee of the moment, with neither the thought nor ambition of setting records. A few months into testing, I ran into Michael Chaffin, co-founder of the Little Rock Gran Fondo, who also was riding a Power+ (the only other person I’ve ever seen on one!). He said the ride comfort was “far superior to any of my carbon bikes,” and that he, too, had been surprised at “how well it climbs” and “handles power in shorter, steep climbs out of the saddle.” He knew another cyclist who had one, a racer named Paul Alexander. Alexander echoes my impression: “What I liked at the very beginning holds true 3,000 miles later: It has that wonderful, classic ride feel you expect out of high-end steel but responds like a modern race bike. I can spend all day in the worst conditions on bumpy roads and still feel fresh enough for the ever-important stop-sign sprints at the end.”

A deep cut is a little-known song from a well-known or respected artist. When musicians cover a deep cut, they hope to unearth a lost treasure, bring a bigger audience to a deserving work, pay homage to someone they appreciate, and maybe add a little something to it if they can. In a too-close-to-call race this may be the greatest all-around steel bike I’ve ever ridden—I’m looking at you, Breadwinner Lolo—certainly one of the most distinctive, and, I think, out of all the bikes I’ve ridden of any kind, the one that best expresses an elegant but raw quality I prize above any other in my personal bicycles.

Bill Strickland is the Rider-in-Chief of Bicycling. His equal passions for cycling and writing have led to the books Ten Points: A Memoir; Tour de Lance: The Extraordinary Story of Cycling’s Most Controversial Champion; Mountain Biking: The Ultimate Guide to the Ultimate Ride; and The Quotable Cyclist. His Bicycling story, “100 Pedal Strokes” won a National Magazine Award for Interactive Feature in 2008. In 2009, he assigned and edited the story “Broken,” which won the National Magazine Award for Public Interest. “The Escape,” the December, 2011, edition of his Bicycling magazine column The Pursuit, was named a Notable story by The Best American Sports Writing. Various editions of his books have been translated into Dutch, German, Hebrew, and Japanese. He uses commas by rhythm and sound, which is a terrible way to do it but makes him happy.